The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

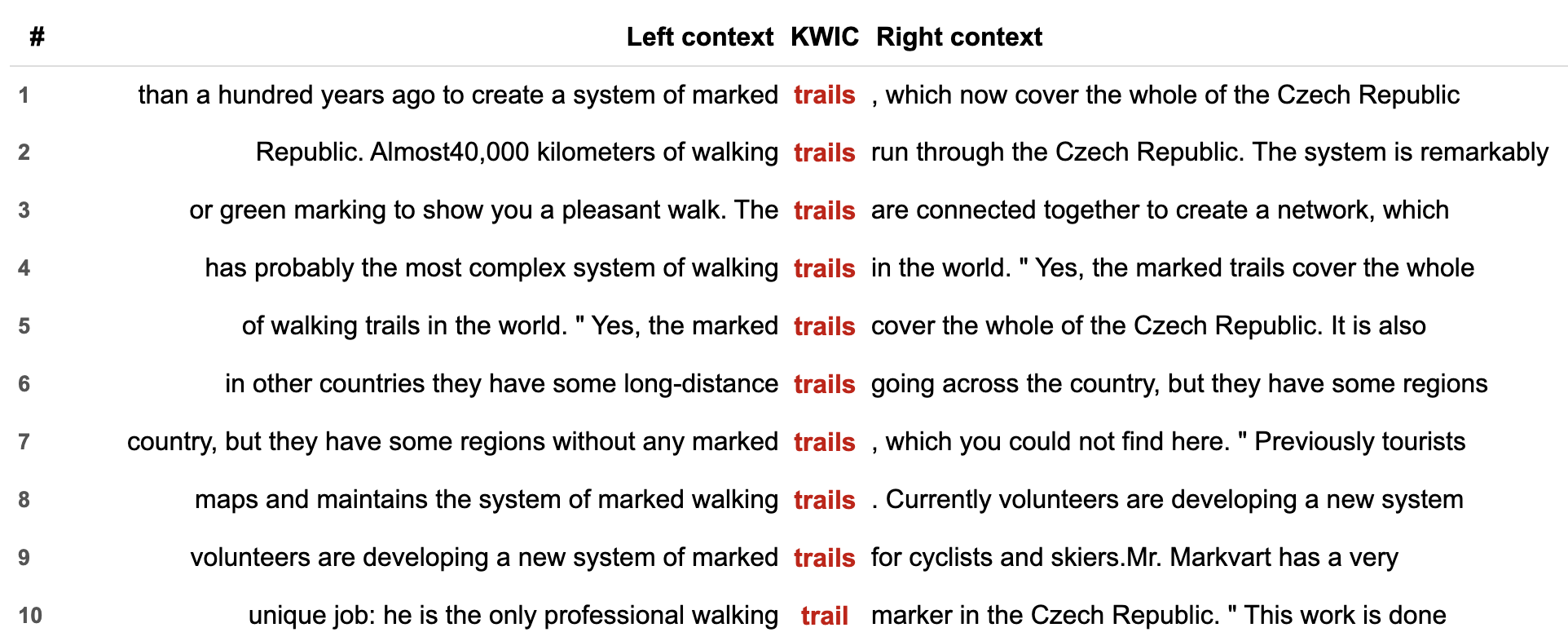

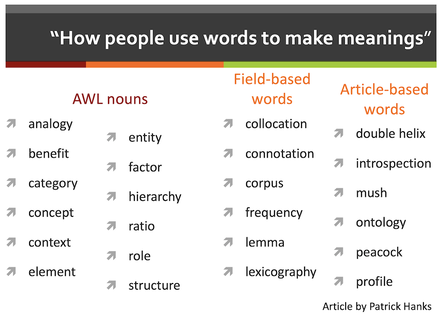

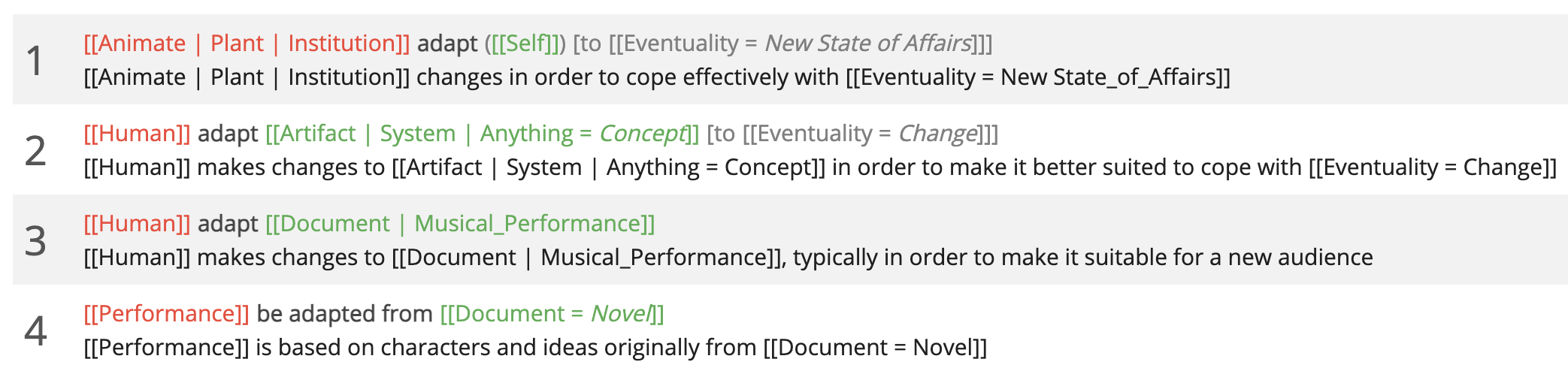

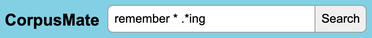

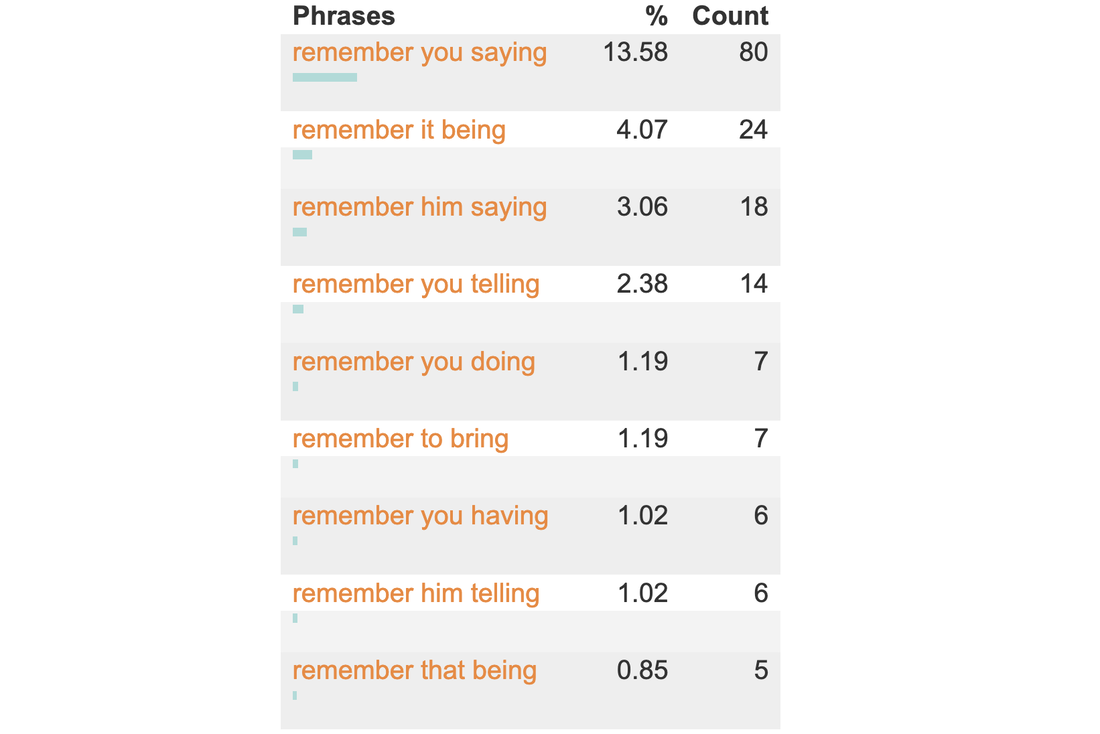

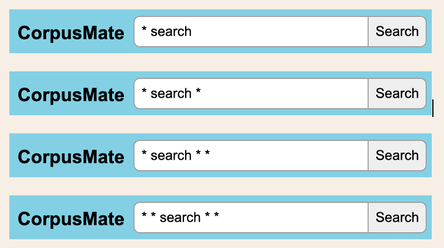

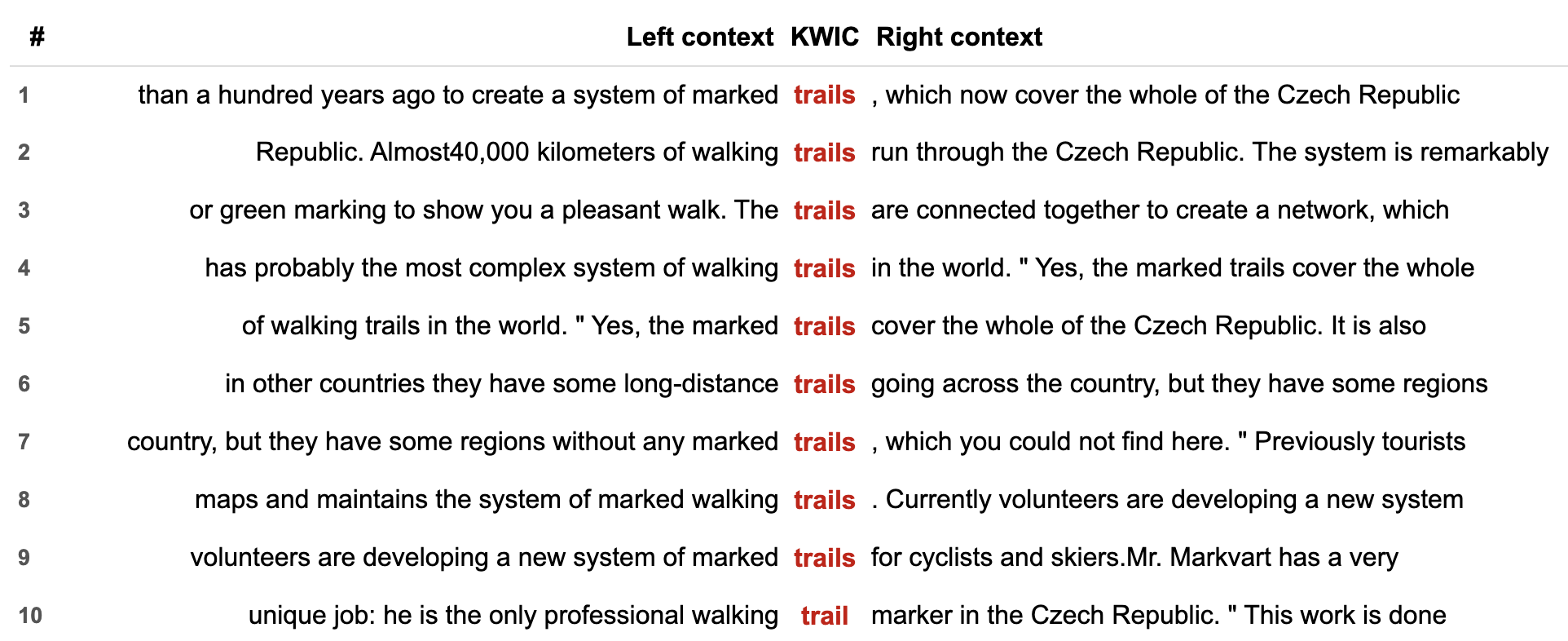

One swallow does not summer make

Hoey in fact studied foreign languages so that he could experience the processes of language learning and the practical applications of linguistic and pedagogical theory. When he was observing language in context, that is by reading and listening, he would notice certain collocations but he needed proof of their typicality before he could consider them worth learning. Just because someone has combined a pair of words does not mean that this combination is a typical formulation in the language. The lexicographer, Patrick Hanks (1940–2024) felt the same: Authenticity alone is not enough. Evidence of conventionality is also needed (2013:5). Some years before these two Englishman made these pronouncements, Aristotle (384–322 BC) observed that one swallow does not a summer make. Other languages have their own version of this proverb, sometimes using quite different metaphors, but all making the same point. In order to ascertain that an observed collocation is natural, typical, characteristic or conventional, it is necessary to hunt it down, and there is no better hunting ground for linguistic features than databases containing large samples of the language, a.k.a corpora. In the second paragraph, Hoey experienced the processes … Is experience a process a typical collocation? This is the data that CorpusMate yields: In the same paragraph, we have the following collocation candidates:

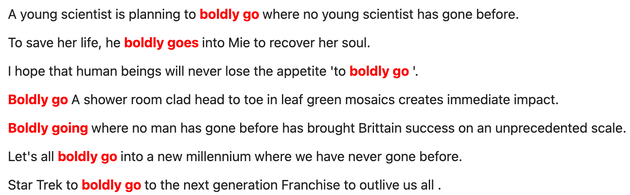

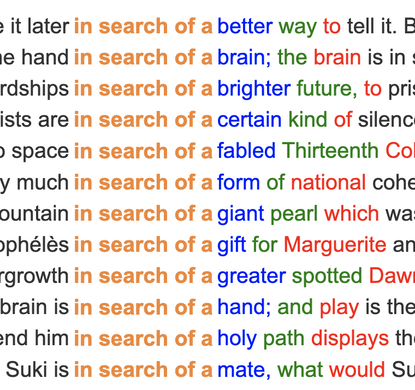

Here is some more data from CorpusMate. In the following example, we have a wildcard which allows for one element to appear between the two words of the collocation. Even in these first 12 of the 59 results, other patterns are evident.  The process of validating your findings through multiple sources or methods is known as triangulation, and it is an essential stage in most research. When we train students to triangulate their linguistic observations, it is quite likely that they are familiar with this process from their other school subjects. This is not just a quantitative observation, i.e. this collocation occurs X times in the corpus. It is qualitative as well: the students observe other elements of the cotext, such as the use of other words and grammar structures that the collocation occurs in. They might also observe contextual features that relate to the genres and registers in which the target structure occurs. They are being trained in task-based linguistics as citizen scientists, engaging their higher order thinking skills as pattern hunters. This metacognitive training is a skill for life that will extend far beyond the life of any language course they are undertaking. Triangulation does not apply only to collocation. Any aspect of language can be explored in this way. You may have noticed the word order in the idiom: does not a summer make. Many people have run with this curious word order and exploited it creatively. It is thus a snowclone. Here are some examples from SkELL. Respect our students' intelligence and equip them to learn language from language. ReferencesCroswaithe, P. & Baisa, V. (2024) A user-friendly corpus tool for disciplinary data-driven learning: Introducing CorpusMate International Journal of Corpus Linguistics.

Hanks, P. (2013) Lexical Analysis: Norms and Exploitations. MIT. Hoey, M. (2000) A world beyond collocation: new perspectives on vocabulary teaching. Teaching Collocation. Further Developments in the Lexical Approach. LTP (ed. Lewis, M.)

0 Comments

Reach for the stars and draw a constellation.How often have you seen claims like these?

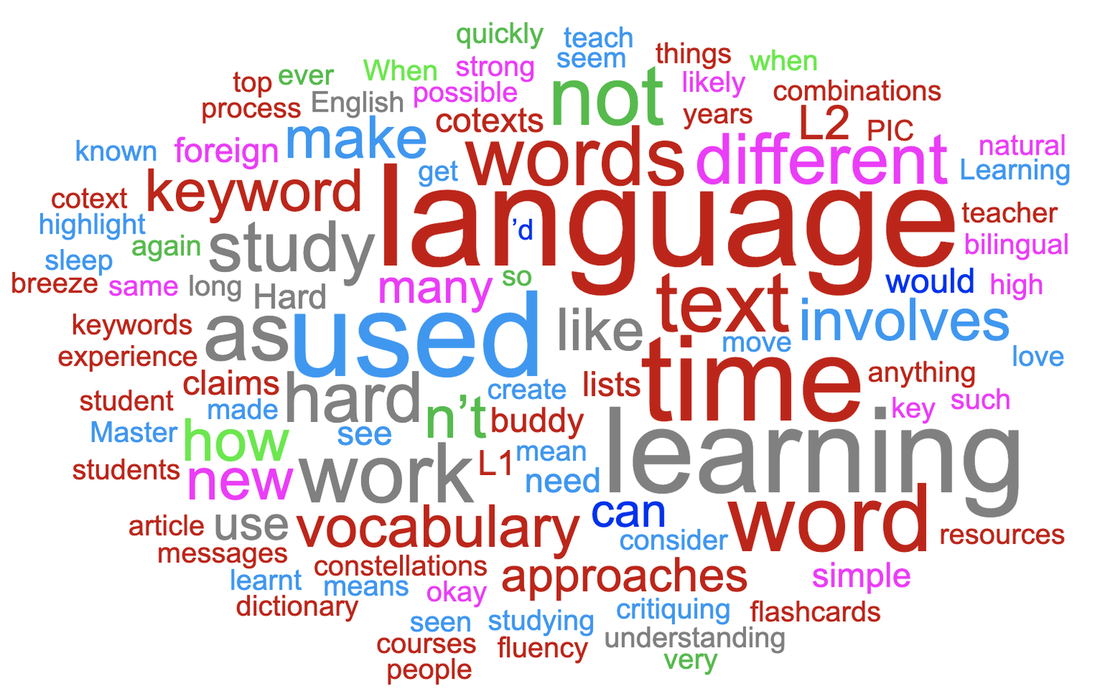

Who would make such claims? Certainly not someone who has achieved a high level of competence in a foreign language. As an eternal language student, and a language teacher and a teacher of teachers, I am pretty certain that you and I have worked hard to get to where we are in our foreign languages. It was not effortless, it wasn’t a breeze and no progress was made while we were asleep. I was so desperate to improve my vocabulary, that I used to sleep with my dictionary under my pillow. No I didn’t, but that is the impression you get from some of these slogans. Learning a language is hard work and there ain’t nothin’ wrong with hard work. Never confuse hard work with hard labour. Hard doesn’t mean boring and monotonous and it doesn’t mean frustrating and unrewarding. The hard work we do when learning a language involves planning, monitoring and revising. It involves understanding what we are learning, which in turn involves connecting what we already know with what is new to us. Hard work involves practising what we have learnt so that it becomes automatic. Hard work involves using our time efficiently, choosing approaches that work for us. This requires us to assess or critique the approaches to language study that are introduced to us if we are fortunate enough to have various approaches. It is worth reflecting on how many different learning experiences we are having while studying – the learning #affordances of an activity. For example, if we are learning a set of English words with their first language equivalents, whether in written lists, on paper or electronic flashcards, in a computer game or being tested by our study buddy, the only connection we make is between the L1 and L2 word. We do not learn how the word is used. This leads us to assume that the L2 word is used in the same way as it used in L1 and this is okay when it works. It is not okay the rest of the time. Psycholinguists refer to this assumption as the semantic equivalence hypothesis (Ijaz 1986, Ringbom 2007). Another issue with learning L1–L2 pairs is the mental processing of the L2 word: what is your mind doing whilst trying to remember a word? Lower order thinking does not make for a rich learning experience. When we are critiquing our approaches to vocabulary study, we need to consider how many different features of words we are learning at the same time. However, when we study the vocabulary of a text in a text, we see how keywords are used differently each time they are used. Yes, their different uses create different messages which means that the author is telling us something new about the keyword each time it is used. These different messages involve different words, which means we can make a diagram of a keyword as it is used in a text. I call these diagrams Word Constellations. We can identify a key word and highlight all of its occurrences in the text, then highlight the words that are used with it. I prefer to do this with #VersaText because it is easy to see the left and right cotexts of keywords in a concordance. You can do this with at least several key words in the text. In critiquing this approach, we need to consider how much the students learnt during the time spent.

If they didn't create a word constellation of a key word in a text, what did they do? How did they spend their time? What learning took place? Once we have a keyword in its multiple cotexts, we can use them as the bases of our own sentences. We might like to use them to form questions to discuss with our study buddy or our favourite AI tool. Here are some simple examples of a chat with Perplexity.ai. Hi. I'm a B1 student of English. Will you be my study buddy today? Of course! I'd be happy to help you with your English studies.

Is this time-consuming? Is it a good use of our time? Are we having strong learning experiences? Are connections forming in our minds that have a high chance of becoming permanent? I used bilingual lists for many years, long after I needed to. I think that if I were to start another foreign language, I would need them as a beginner. But applying what I have actually known for a long time, I would move as quickly as possible to studying words with their natural cotexts. It may be the case that people who make claims like those at the top of this article do actually teach vocabulary in cotext, but from the courses and resources that I have seen over the years, this does not seem very likely. If you or your students ever create word constellations, I’d love to see them. And I would love to know what the process led to. Feel free to join the VersaText Facebook Group where you can share your experiences and learn from others. ReferencesIjaz, I. H. (1986). Linguistic and cognitive determinants of lexical acquisition in a second language. Language Learning, 36(4): 401-451

Ringbom, H. (2007). Cross-linguistic similarity in foreign language learning (Vol. 21). Multilingual Matters. Veselá, Z. (2003) Czech Republic’s unrivalled system of marked walking trails. Radio Prague International, 5.12.2003. Collocation and VersaTextI had an email from a teacher who loves using my VersaText tool with his students. In addition to the very welcome and rarely received praise for VersaText, he was enquiring into the possibility of adding a collocation feature. As you know, VersaText works with single texts, its slogan being, “learning language from language, one text at a time”, collocations are vanishingly rare. In fact, “vanishingly rare” is a strong collocation in English. Check out the examples in #SkELL.

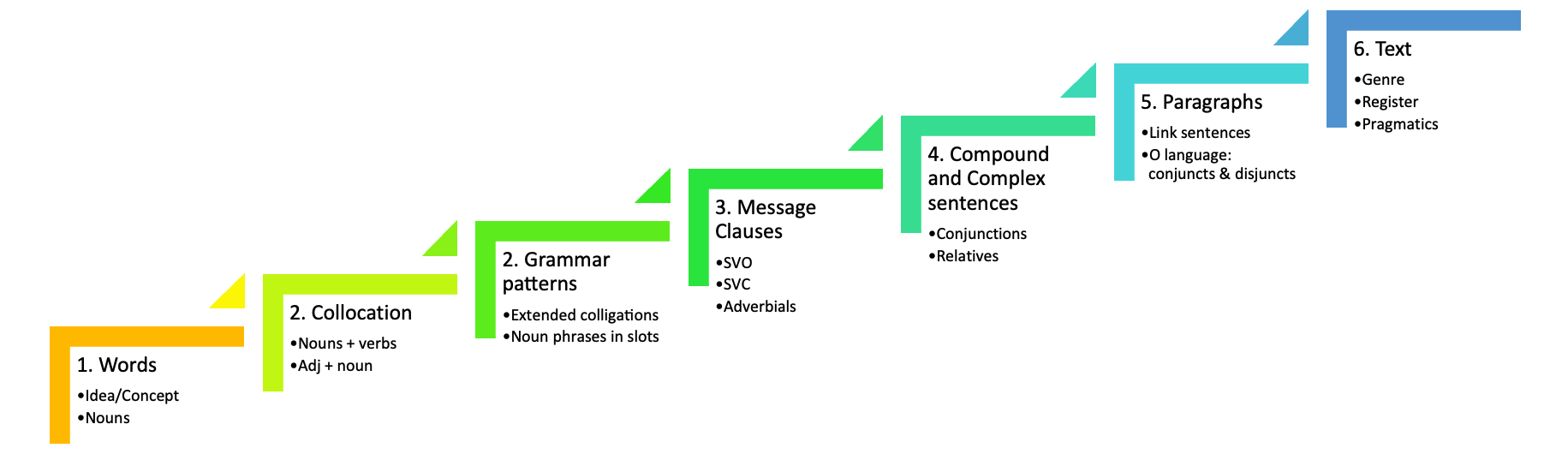

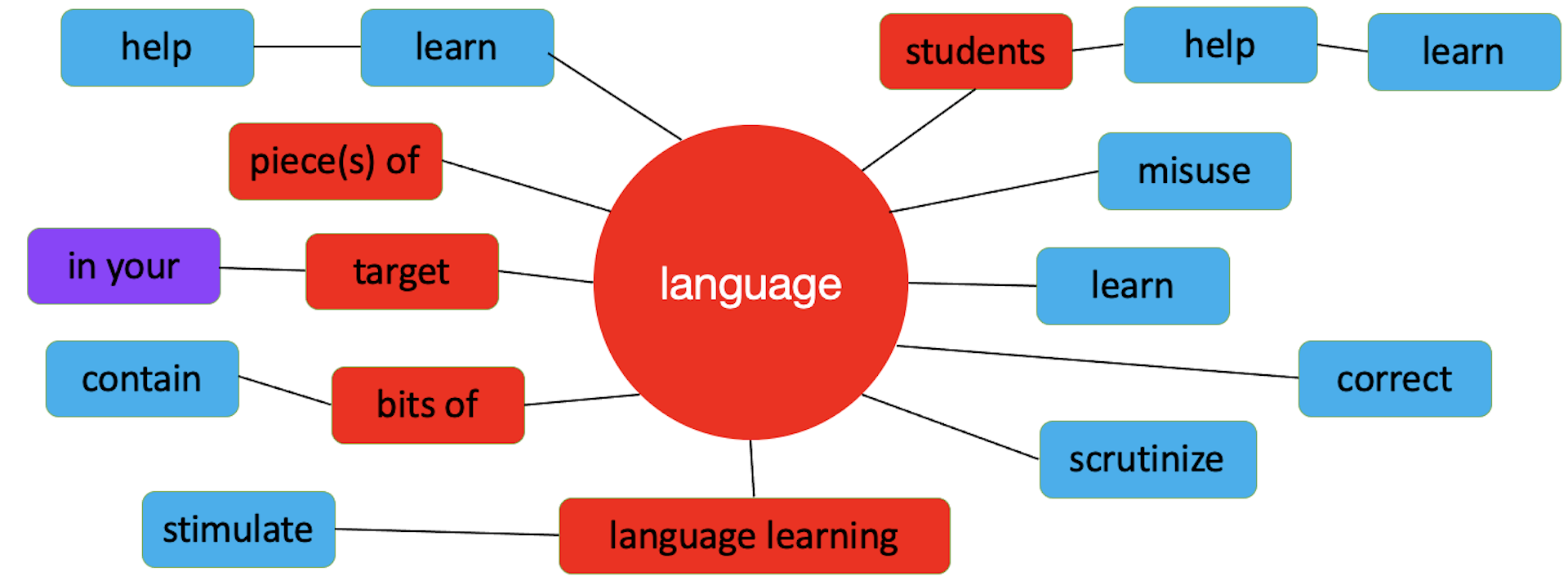

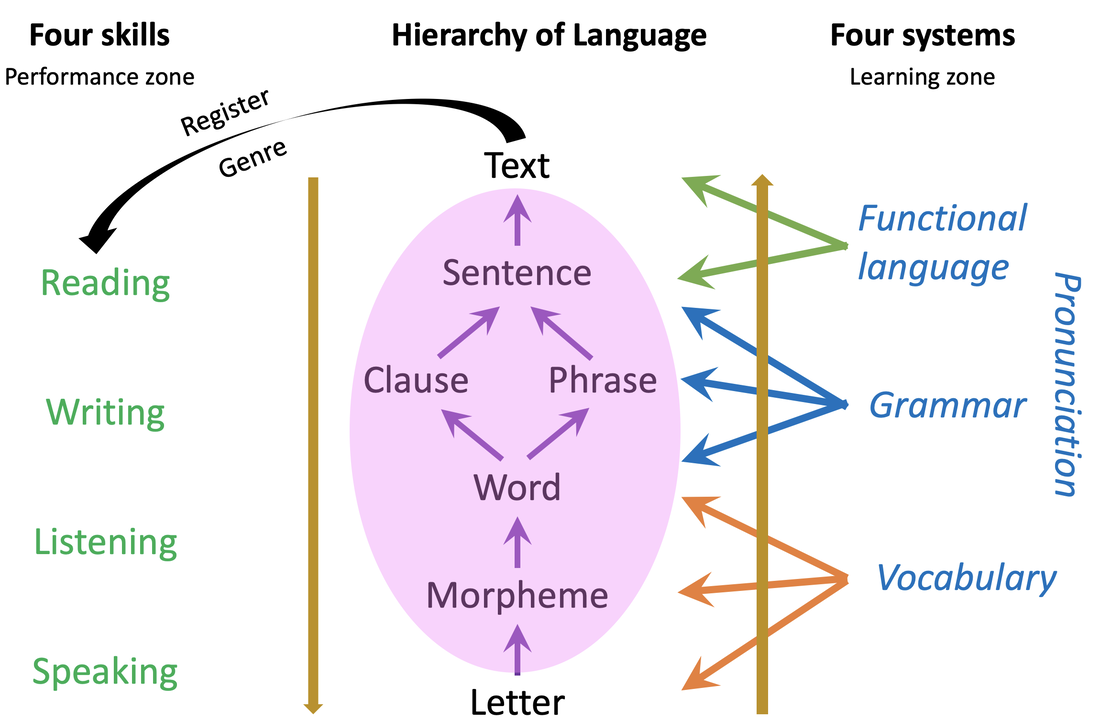

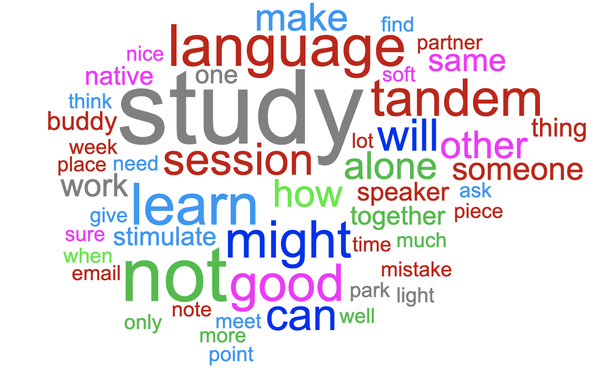

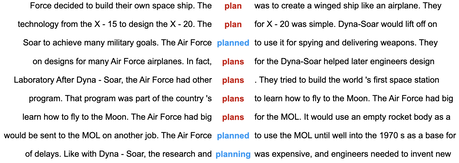

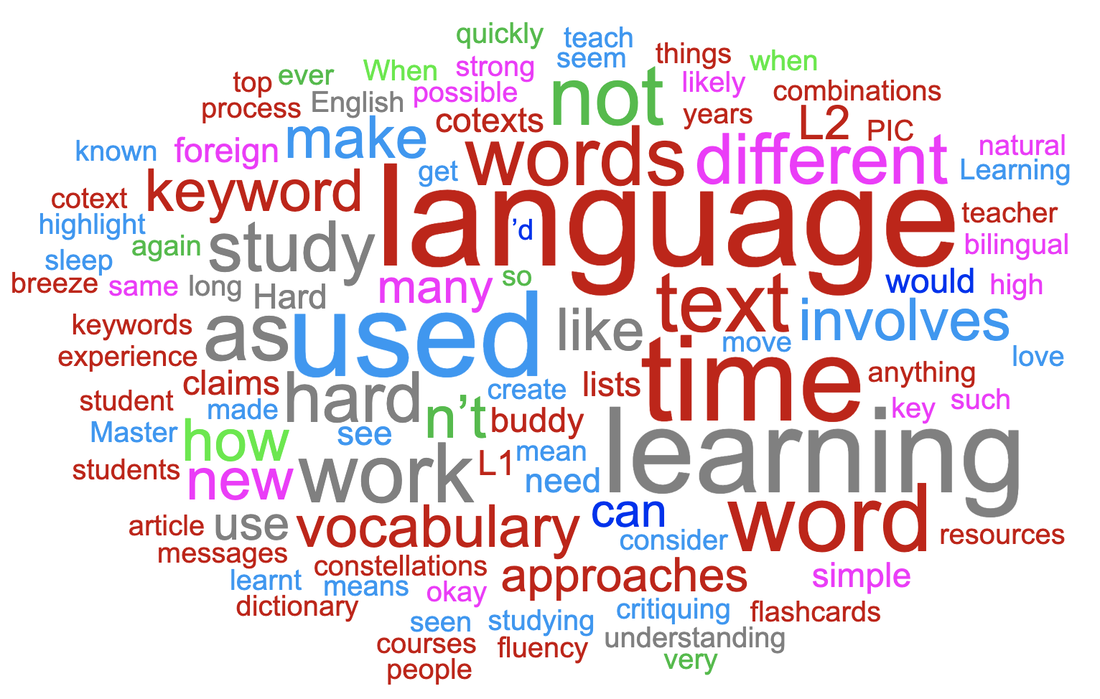

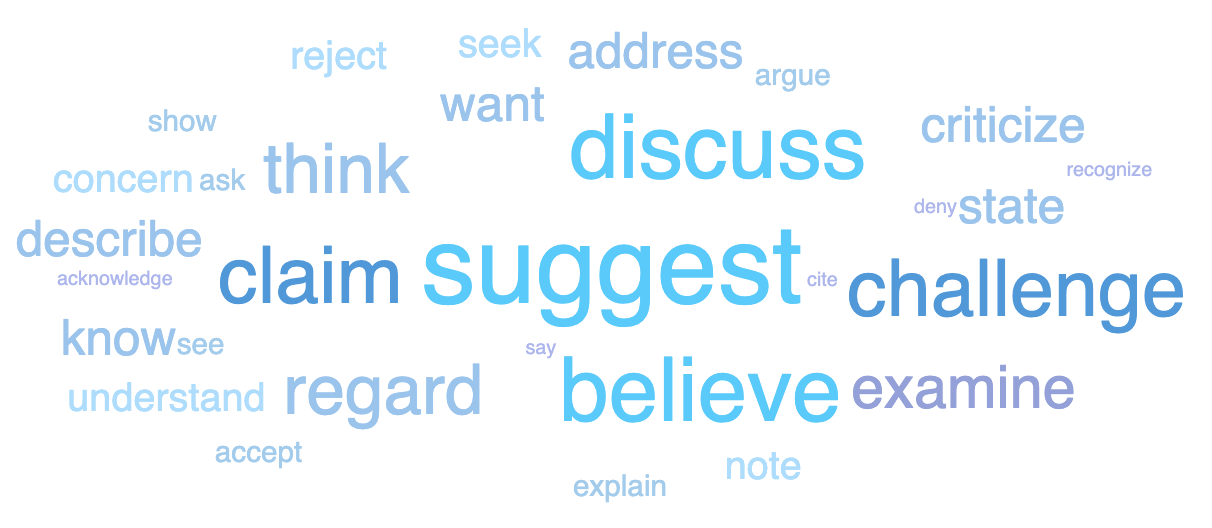

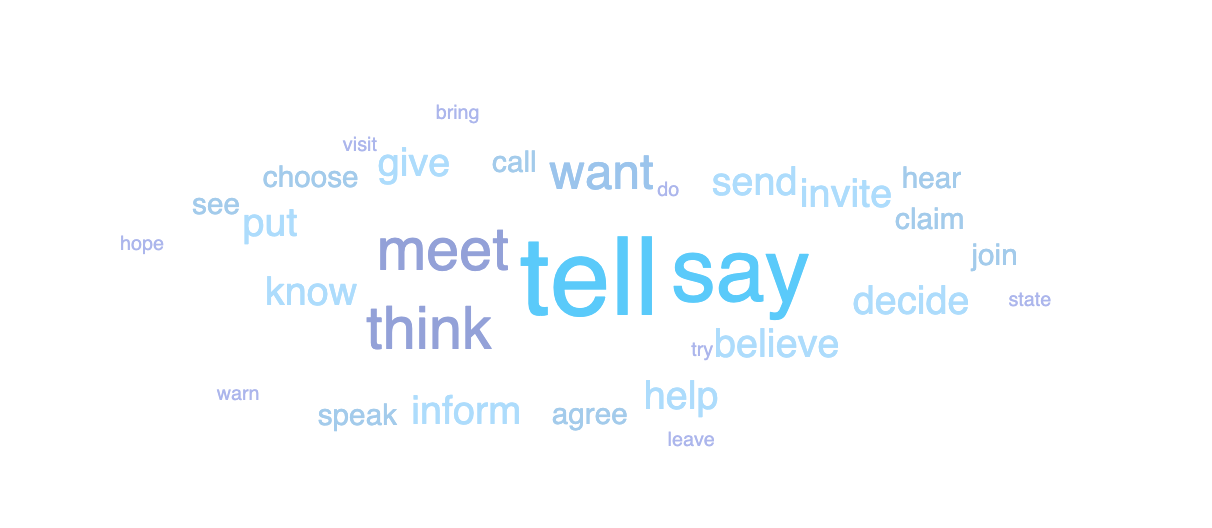

#Collocation is defined variously. First and foremost, collocation consists of two content words of different parts of speech. Compound nouns and adjectives, phrasal and delexical verbs are not collocations. And neither are words that combine with that/ -ing / inf / wh-/prepostions. These are colligations and offer very little choice, if any. You’ve all seen gap fills in coursebooks and exams that test this. Collocation does permit some variation, but within limits of acceptability if you are going to use the patterns of normal usage of the language. One category of definitions of collocation revolves around statistical frequency. These definitions rely on the number of times words occur in close proximity to each other. The verb collocates of trouble, for example, occur frequently within four words before and/or after the noun in SkELL's huge sample of English. Other definitions of collocation are phraseological: cause trouble is the core of a clause, which is the essential structure that creates Messages, which in turn constitutes text. Up the Hierarchy of Language we go! Most key words in most texts collocate with different items because the author is telling us something new about the word. And this is why a collocation tool in VersaText would be by and large redundant. One thing we can be sure of in a text is that the author is not going to repeat the same message repeatedly, again and again, over and over, unless they have some rhetorical reason for doing so. Here is an example. In VersaText’s sample text, Learning Zone (a transcript of a TED Talk), we see that the verb spend is frequently used with time, and with other time words, e.g. minutes, hours, our lives. It occurs 13 times in the text. Time occurs 28 times in the text and is used thus: CTRL F in the browser highlights the nominated word as it occurs in the cotext of the target word. Improve occurs 15 times in the text, each time in a different Message. This is far more typical of words in text than a frequently used collocation like spend time. Go to VersaText, select the Learning Zone text from the list, then click Wordcloud at the top. If you want the lemma of improve, for example, choose the lemma radio button under the word cloud. Click on any word to see its concordance in this text. This motivates many discovery learning tasks for the students. If you want to learn more about studying and teaching English with VersaText, click the Course button at the top of the VersaText pages. My phraseological approach to collocations in single texts is the Word Constellation. See my blog post linked below. This is a word constellation. It is built upon a VersaText concordance of the word language in text about language learning.

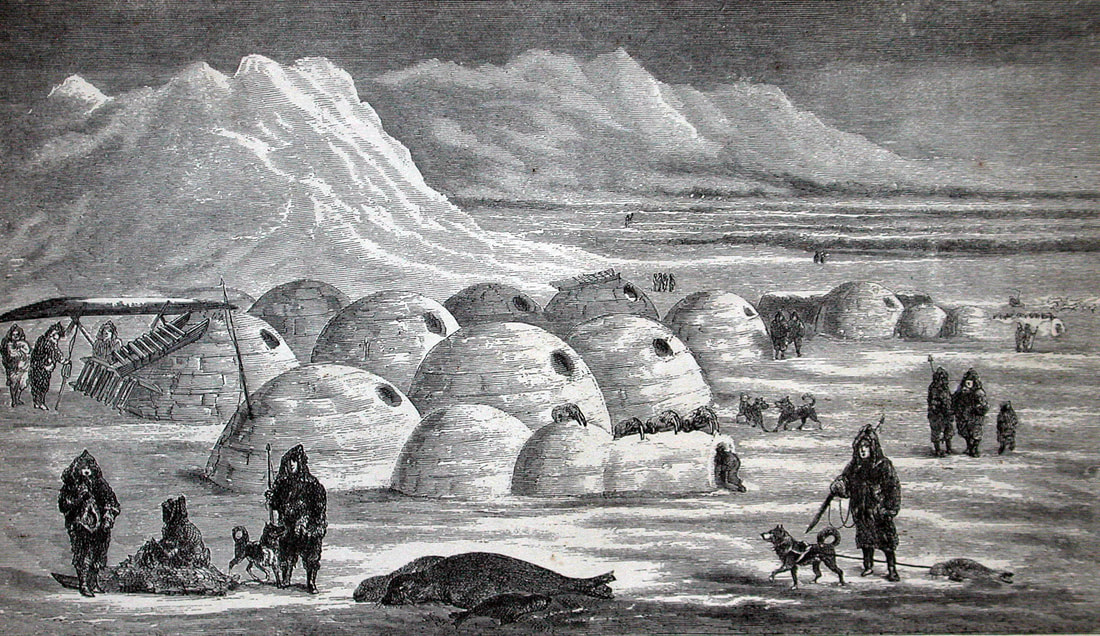

Snowclones adriftIt is a truth universally acknowledged, that a university student in possession of a strong academic vocabulary will be well on the way to toughing out their studies, for we know that when the going gets tough, the tough rush headlong into their studies and boldly go where no student has gone before. And other such exploitations of well-known expressions. You can see more examples of them in the SkELL corpus. And when you do explore them in SkELL, you can read the full sentences and make a wide range of observations. You can discover their original forms and observe how various people have exploited them. And talked about them. Remember that corpora generally consist of thousands of texts created by different individuals and a search provides a sample of the target word or structure. Because SkELL’s corpus is drawn from the internet, you can copy a sentence and Google it to see it in its source text and consider the author’s motivation for using it. You can consider the genre and register of the text: it is unlikely that they would be used in academic papers or in formal conversations. As you have probably heard, Eskimos have 17 words for snow, far more than any other language. This claim is as fatuous as the Great Wall of China being the only man-made object visible from space. And both of these statements are also snowclones, the term used for these linguistic exploitations. I have it on good authority (Wikipedia) that the term was coined by Glen Whitman, economics professor, in 2004, and the linguist, Geoffrey Pullum, endorsed it. Whitman’s inspiration for the term was the fatuous Eskimoan snow claim. Here are a few more snowclones that I have collected over the years. They have various origins and standard uses in English, but all are variously exploited as snowclones.

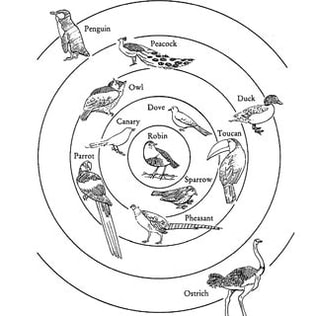

Like all linguistic phenomena, snowclones have been in existence much longer than the term coined to describe them. A term endows a phenomenon not only with a certain gravitas but a recognition that it has a set of features that an entity needs to be worthy of the name. If it has all of the required features it is a prototype (Rosch). Eleanor Rosch Most things deviate to some extent from prototypes, but if they have enough of the features in an adequate proportion, they can be thus labelled. The beloved example of semanticists is birds: which features of pigeons, eagles, emus, penguins and pterodactyls do they possess to be categorised as birds? Another fine example is the English language: which features of English do spoken Texan, Irish football journalese, and academic written English all possess? This makes for an interesting Venn diagram and it leads to a description of “core” English. A nice activity, by the way! Terms are of much use to language students and misuse impedes their progress. We are all familiar with the misnomers, past tense and past participle. As Michael Lewis convincingly conveyed, the past tense is actually about remoteness – in time, in reality, and in social distance. The past participle is a non-finite form and by definition cannot express time. Compound nouns and phrasal verbs are not collocations, and delexical verb structures are neither collocations nor phrasal verbs. Restaurant, bistro and canteen are co-hyponyms, not synonyms. The use of by in passive structures is not a preposition but a particle. When you know the defining features of linguistic phenomena, you can observe them, study them, learn them and use them with confidence. Our English students who also study maths, science, biology, sport, history, geography, literature and the rest, understand very well that their success depends on a profound understanding of the terminology of their field(s). They also know that their professional success demands a professional level of English. Our students deserve as accurate a description of the language as we can provide them. Until you know that snowclones are an identified and labelled feature of the language, you can’t look them up, talk about them, research them, or tag the next one you hear as one. But now you can.

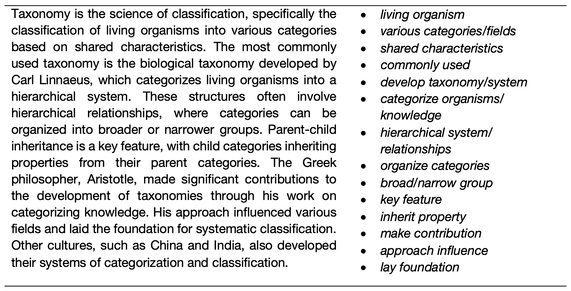

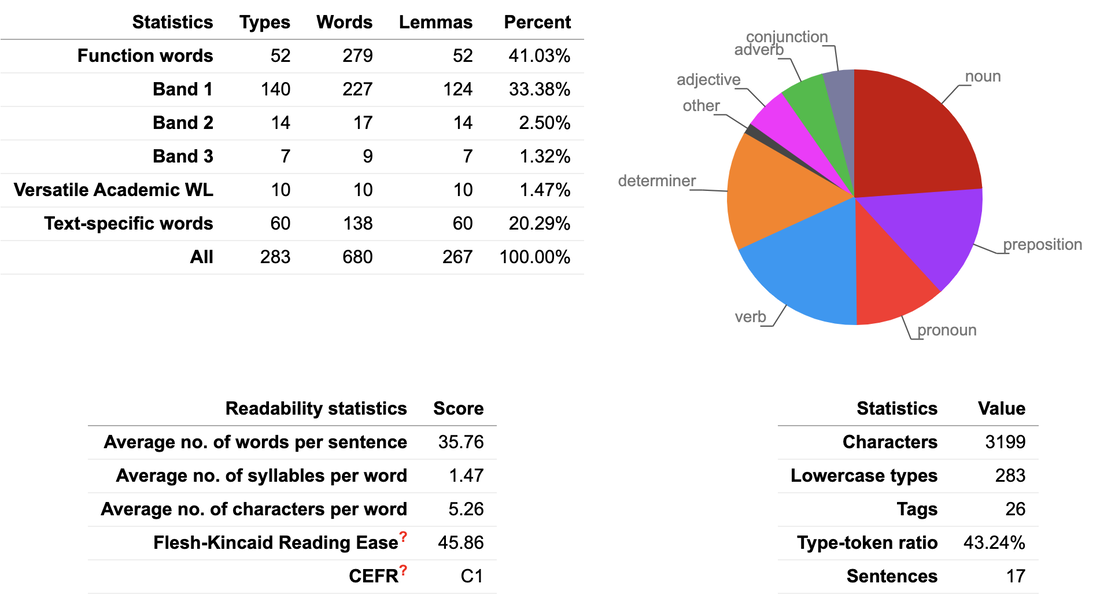

Ask not what students can do for you—ask what you can do for your students! If you have any other favourite, shareworthy snowclones, please add them in the comments below. It would be great to develop this. Learning language from language with VersaTextEvery layer of the hierarchy of language can be explored by students in a text. The exploration of Texts as Linguistic Objects (TALO) reveals how an author has used words and word forms, combined them as collocations and colligations, formed phrases and clauses that are linked with metadiscourse chunks to ultimately form texts. This is the bottom-up process that we employ both subconsciously and consciously when we speak and write. As well as being linguistic objects, Texts are also Vehicles of Information (TAVI) which invoke top-down processes as we combine the content of the text with what we know about the world through schemata, general knowledge and our expectations of text types. In this way, readers and listeners are engaged in their own personal knowledge creation. Thirdly, Texts are Springboards for Production (TASP). We respond to texts by combining several texts on the same topic, by critiquing aspects of the text, and by discussing the potential impact of this new knowledge, for example. To put texts under the microscope, VersaText is an open access, web-based resource that allows teachers and students to paste in a single text. The program provides several tools that foster discovery learning. The first tool is the word cloud, which depicts not only the relative frequencies of words in a text, but it colour-codes part of speech. The word cloud is highly customisable: the number of words, the choice of words vs. lemmas, which parts of speech to show. The relative sizes of words in the word cloud illustrate the extent of repetition in a text and repetition is the most commonly used resource to create lexical cohesion in text (Halliday & Hasan, 1976). When you click on a word in the word cloud, it shows a concordance of that word in the text. The concordance lines are in text order, which shows how the meaning of a key word evolves through different cotexts (Hoey, 1991). Inferring the meaning of an unknown word when it is shown in at least several cotexts is a far more realistic expectation than doing so from a single meeting with a word. It is possible to observe the use of articles with the first and subsequent noun references. Other colligation patterns can also be observed, such as the use of that and wh- clauses, and bound prepositions. Collocation, when defined as a frequency phenomenon, is not a pertinent feature of a single text, as a collocation is a unit of meaning that authors do not need to repeat. A phraseological definition of collocation is therefore more appropriate here (Partington, 1998). It is not uncommon for a text to include many verbs that collocate with a key noun. Observing collocation in such authentic contexts is an authentic learning task, as is employing said collocations in TASP. As students observe the key words in a text and their cotexts that create each of the author’s messages or propositions, they are not only engaged in TALO but they are also deepening their TAVI. Engaging such higher order thinking skills respects the intelligence of our students unlike so-called “tasks” such as multiple choice comprehension questions and gap filling. In addition to word clouds and concordances, VersaText provides text statistics including an estimate of a text’s CEFR level. It also shows the percentages of words that are function words, three bands of content words, academic words and text-specific words. It also lists all of these words in these categories in tables which can be used by teachers and students who are especially focused on vocabulary development. The opportunity to put the language of a single text under such a microscope is invaluable to students of CLIL, EMI and ESP, as the texts are models of the language of subjects and fields that the students need to have a productive knowledge of, if they are to be acculturated into their subject disciplines. This is essential for TASP. Feel free to join the VersaText Facebook Group where you can share your experiences and learn from others. ReferencesHalliday, M.A.K. & Hasan, R. (1976) Cohesion in English. Longman

Hoey, M. (1991) Patterns of Lexis in Text. OUP. Johns, T., Davies, F. (1983) Text as a vehicle for information: the classroom use of written texts in teaching reading in a foreign language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 1 (1) Partington, A. (1998) Patterns and Meanings: Using Corpora for English Language Research and Teaching. John Benjamins. Patrick Hanks 1940–2024 |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|