The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

A few issues with traditional vocabulary teachingHaving been engaged in language study for over four decades, made attempts on four foreign languages and witnessed the growth of my first language, English, I can assure you that I have invested a great deal of time into learning vocabulary. Much of it was wasted. Much of it was spent learning useless words in ways that did not teach me how the words work in the target language. Vocabulary learning strategies were not taught. It was simply assumed that students would memorise context-free bilingual lists as if the L2 words worked in the same way as in L1. If I was lucky, my attempts to use the words in sentences and texts were returned bespattered with red ink highlighting collocation and colligation errors in particular. In my experience as a language learner, teacher, trainer and author, I consider the following activities useful but limited:

The reasons I consider these procedures limited:

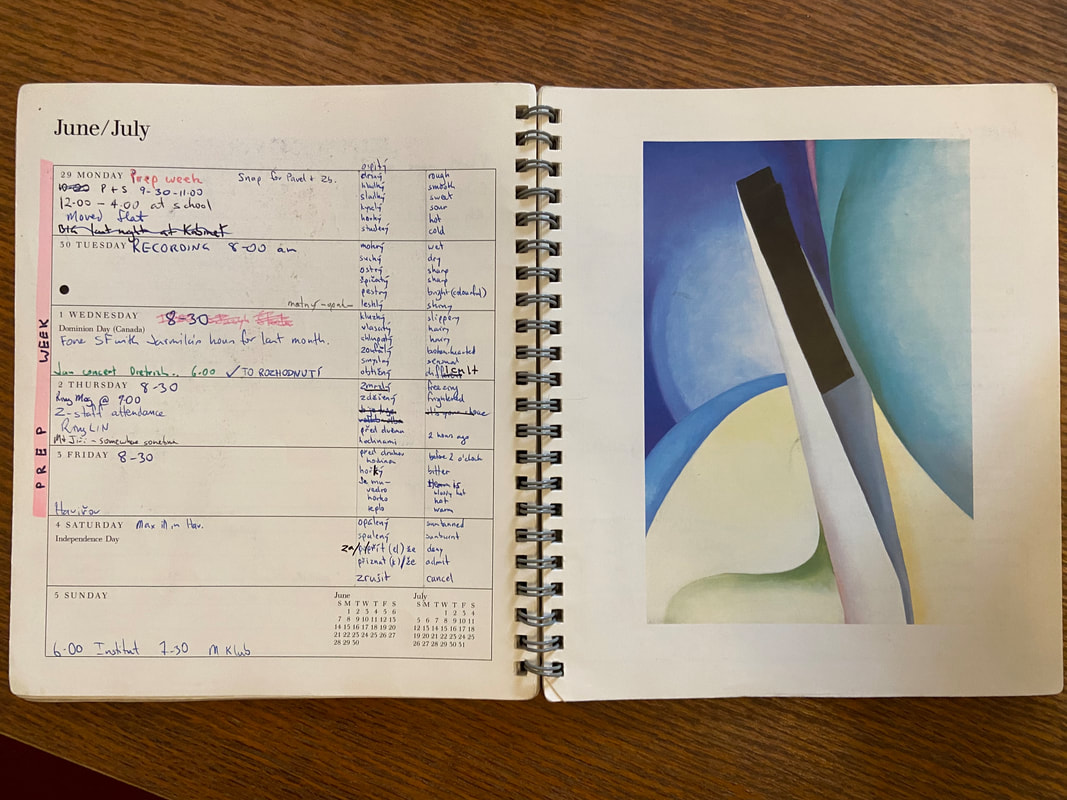

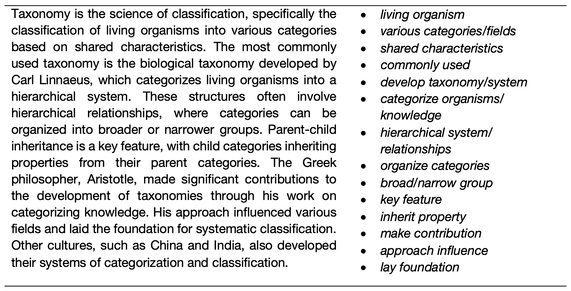

You can probably think of some counter examples. And so can I. But what I see in contemporary course books does not negate most of the above. Alternatively, we could respect our students' intelligence and creativity.We can task our students with identifying relationships between words and within words, and depict them meaningfully. These examples come from my Versatile Blank Book, which you can read about on this site.

0 Comments

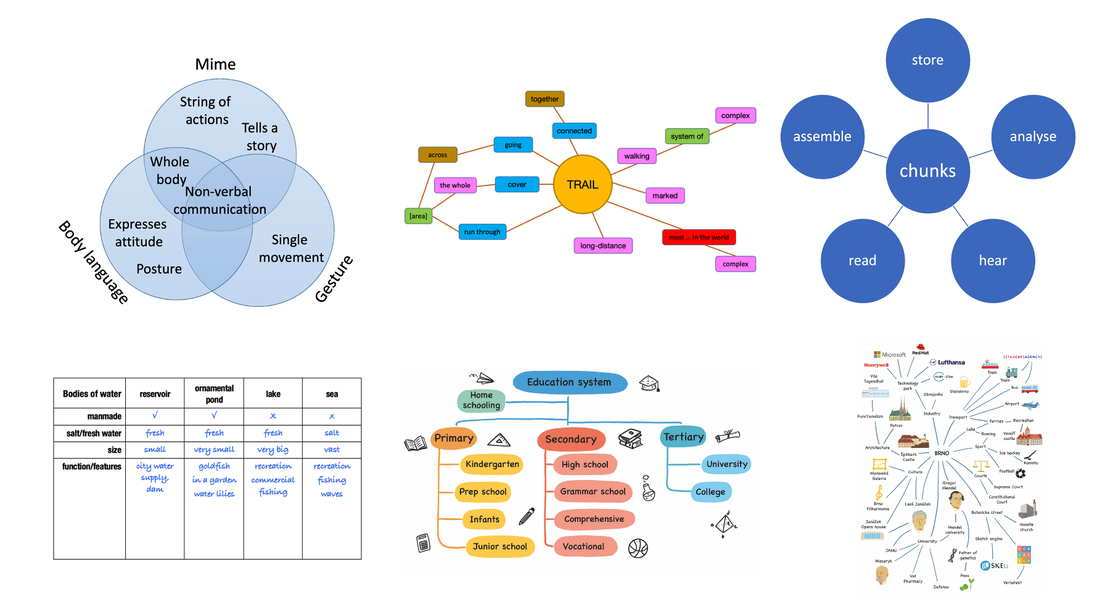

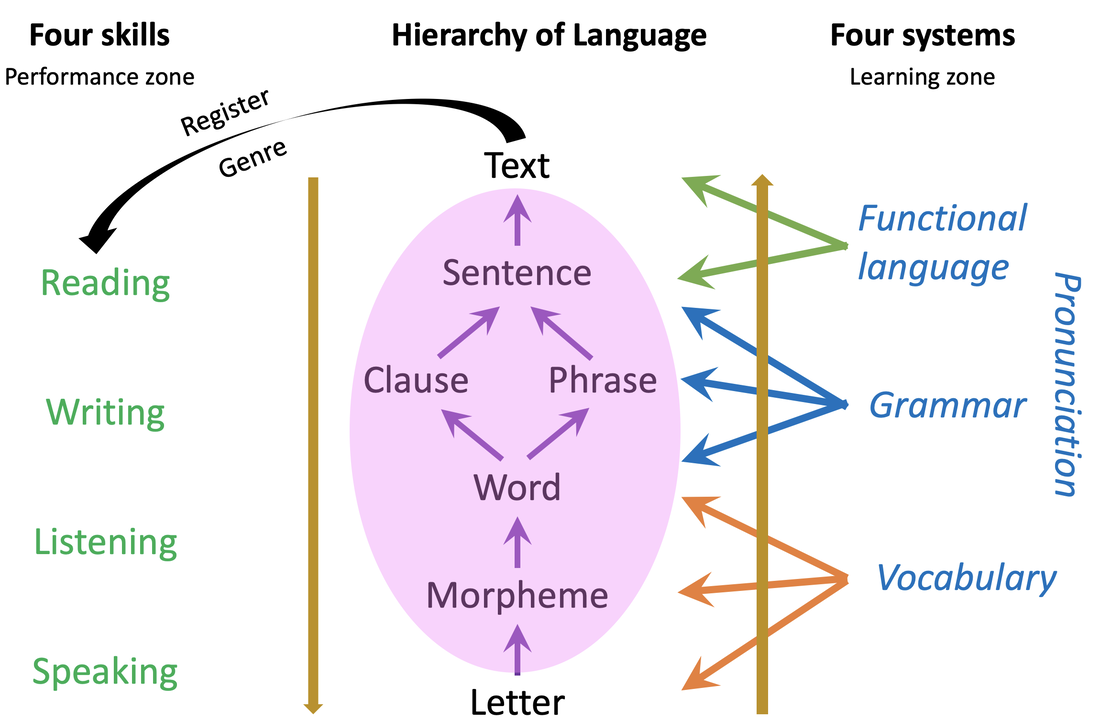

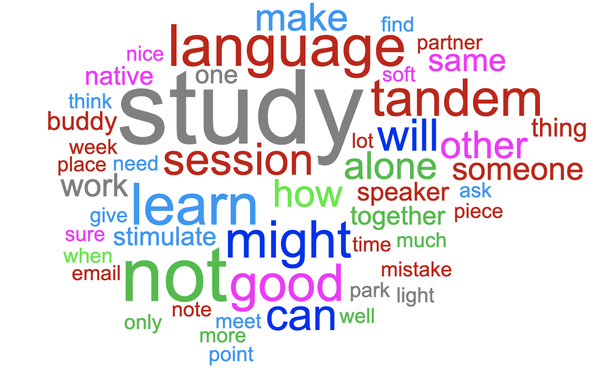

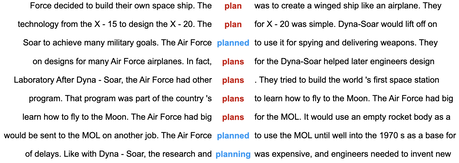

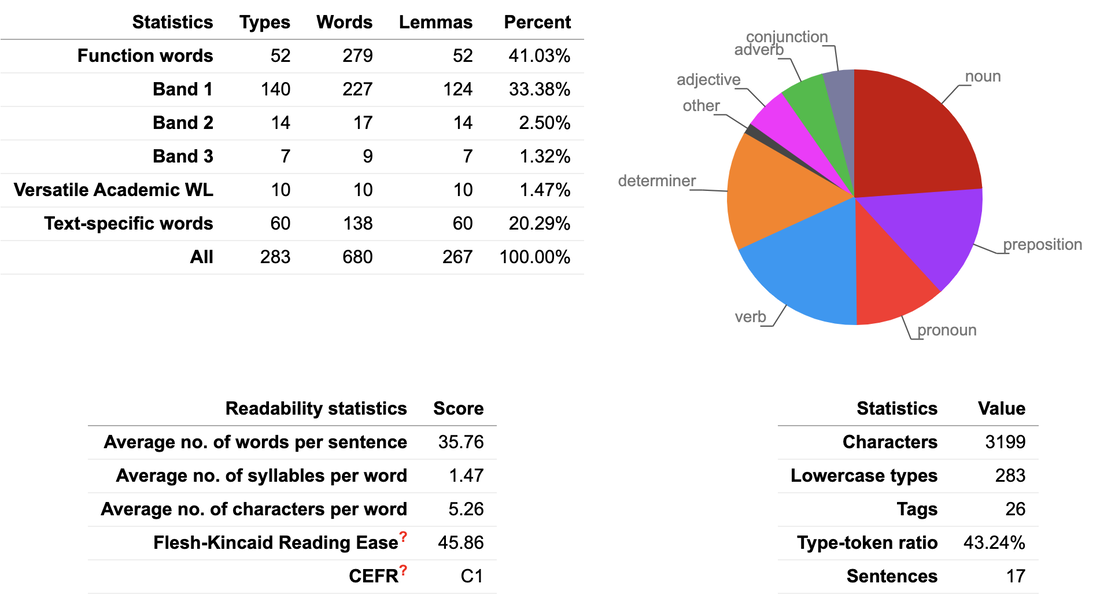

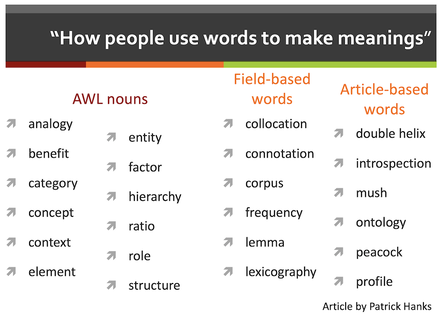

Learning language from language with VersaTextEvery layer of the hierarchy of language can be explored by students in a text. The exploration of Texts as Linguistic Objects (TALO) reveals how an author has used words and word forms, combined them as collocations and colligations, formed phrases and clauses that are linked with metadiscourse chunks to ultimately form texts. This is the bottom-up process that we employ both subconsciously and consciously when we speak and write. As well as being linguistic objects, Texts are also Vehicles of Information (TAVI) which invoke top-down processes as we combine the content of the text with what we know about the world through schemata, general knowledge and our expectations of text types. In this way, readers and listeners are engaged in their own personal knowledge creation. Thirdly, Texts are Springboards for Production (TASP). We respond to texts by combining several texts on the same topic, by critiquing aspects of the text, and by discussing the potential impact of this new knowledge, for example. To put texts under the microscope, VersaText is an open access, web-based resource that allows teachers and students to paste in a single text. The program provides several tools that foster discovery learning. The first tool is the word cloud, which depicts not only the relative frequencies of words in a text, but it colour-codes part of speech. The word cloud is highly customisable: the number of words, the choice of words vs. lemmas, which parts of speech to show. The relative sizes of words in the word cloud illustrate the extent of repetition in a text and repetition is the most commonly used resource to create lexical cohesion in text (Halliday & Hasan, 1976). When you click on a word in the word cloud, it shows a concordance of that word in the text. The concordance lines are in text order, which shows how the meaning of a key word evolves through different cotexts (Hoey, 1991). Inferring the meaning of an unknown word when it is shown in at least several cotexts is a far more realistic expectation than doing so from a single meeting with a word. It is possible to observe the use of articles with the first and subsequent noun references. Other colligation patterns can also be observed, such as the use of that and wh- clauses, and bound prepositions. Collocation, when defined as a frequency phenomenon, is not a pertinent feature of a single text, as a collocation is a unit of meaning that authors do not need to repeat. A phraseological definition of collocation is therefore more appropriate here (Partington, 1998). It is not uncommon for a text to include many verbs that collocate with a key noun. Observing collocation in such authentic contexts is an authentic learning task, as is employing said collocations in TASP. As students observe the key words in a text and their cotexts that create each of the author’s messages or propositions, they are not only engaged in TALO but they are also deepening their TAVI. Engaging such higher order thinking skills respects the intelligence of our students unlike so-called “tasks” such as multiple choice comprehension questions and gap filling. In addition to word clouds and concordances, VersaText provides text statistics including an estimate of a text’s CEFR level. It also shows the percentages of words that are function words, three bands of content words, academic words and text-specific words. It also lists all of these words in these categories in tables which can be used by teachers and students who are especially focused on vocabulary development. The opportunity to put the language of a single text under such a microscope is invaluable to students of CLIL, EMI and ESP, as the texts are models of the language of subjects and fields that the students need to have a productive knowledge of, if they are to be acculturated into their subject disciplines. This is essential for TASP. Feel free to join the VersaText Facebook Group where you can share your experiences and learn from others. ReferencesHalliday, M.A.K. & Hasan, R. (1976) Cohesion in English. Longman

Hoey, M. (1991) Patterns of Lexis in Text. OUP. Johns, T., Davies, F. (1983) Text as a vehicle for information: the classroom use of written texts in teaching reading in a foreign language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 1 (1) Partington, A. (1998) Patterns and Meanings: Using Corpora for English Language Research and Teaching. John Benjamins. Patrick Hanks 1940–2024 |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|