The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

Casual encounters rarely lead to life-long relationshipsThe title of this post is a sentence in a book I don’t seem to be able to finish: Grammar, Vocabulary and Everything in Between (GVEB). It’s a book full of language learning tasks on whose cover I would like to plaster “More fun than Murphy". Better not :-). But what is holding me up at the moment is the writing of another task book called After IELTS (and e-course), which is for students who have passed the Academic IELTS and will soon start their university studies in English, perhaps in the belief that IELTS prepared them for university level work. This belief was at least partly engendered by the low IELTS score that the university declared adequate for this level of study. I witnessed many hundreds of students in exactly this situation being seriously ill-prepared. So, when I finish writing After IELTS, I will finally finalise the final version of GVEB. Watch this space! In the context of GVEB, "casual encounters rarely lead to life-long relationships” refers to the lack of long-term impact that a meeting with a word whilst reading, listening and watching has. It’s like being in your local shopping mall or at a reception with hundreds of people milling about. They all share the properties of [HUMAN] – walking upright, head, body, four limbs, clothed, a sense of purpose. There will be some outliers – very tall, blue hair, in a wheelchair, atypically dressed, looking lost and confused. Some people look very familiar, some less familiar, and others not at all. It will be clear that some people are there with another person, and others are functioning in small groups. Some people will be helping others and some people will be performing their roles in their milieu independently. If we don’t stop and get to know someone in a crowd or a word in a text, they are not going to enter into our consciousness or become a part of our understanding of the world. They are just going to be a part of “the general mush of goings on”, to quote J. R. Firth, whom some regard as the founding father of British linguistics. People do stop, even crouch, to pat someone’s dog or goo-gah someone’s child as a coy excuse to talk to the accompanying adult. At a reception, people have the shared context of the event itself to thaw the ice. When I was teacher training for the BC in Tashkent, the British Ambassador held occasional garden parties. At one such event, I walked up to two women nursing wines and announced that I didn’t know anyone there. They said they didn’t either. We got chatting and ended up Sunday lunching together for the next few months till COVID put paid to that. And a few other social niceties and professional MOs. We three have a Telegram group and stay in touch. I’ve met them both once since. They have most definitely become a part of my worldview. If we want new words to become part of our "wordview", a fleeting meeting ain’t gonna cut it. We can read and listen and watch till the cows come home, but if we don’t devote some attention to the desirably unfamiliar, they will remain unfamiliar and the desire will remain unquenched. If you have never seen the word unquenched before, be not surprised. In the 52 billion (sic) word corpus, EnTenTen (Sketch Engine), it occurs a paltry 1,292 times. By comparison, desire occurs 5 million times in said corpus. Even the lemma of quench only occurs 112,342 times. The lemma includes quench, quenched, quenching. Does quench typically keep company with desire? Yes, 821 times. It more typically keeps company with thirst, hunger, craving and curiosity. The words that typically come between quench and one of these objects are my, your, etc., In the chunk, quench the thirst of (3,105 times), thirst is mainly used metaphorically, e.g. the thirst of millions. Quench also collocates with fire, flame, furnace. If you encounter quench as a new word in a text, it is unlikely that its meaning would be clear from this single casual encounter, let alone its usage. To befriend it, we need to invoke J. R. Firth’s most famous maxim, You shall know a word by the company it keeps (1957). For a relationship to develop, you need to spend some time together, asking questions, discussing, structuring your understanding and restructuring it as each new tidbit falls into place. It also helps if we have structures in place to slot new findings into. If we know the structure, someone verbed their body part, e.g., he cut his nails, she washed her hair, it is not a great leap for humankind to embrace, he quenched his thirst. If you have been taught not to use a preposition to end a sentence with, then the first sentence in this paragraph may have made you a little antsy. I have often teased my students with, One swallow does not a summer make, since the aberrant word order grates. When we search a corpus for "does not a .* make", it is clear that this is a systematic linguistic exploitation, as the great British lexicography, Patrick Hanks refers to such creative uses of language. When we meet pieces of language several times and then explore them, they become entrenched in our thinking. After all, one swallow does not a summer make. Instead of rejecting them as a one-off creative use of language, or worse, a mistake (yikes!), we find or make a home for them in our thinking about the language. Thus begins our relationship with them. ReferencesFirth, J.R. (1957) Papers in Linguistics 1934 – 1951. Oxford University Press.

Hanks, P. (2013) Lexical Analysis: Norms and Exploitations. MIT.

0 Comments

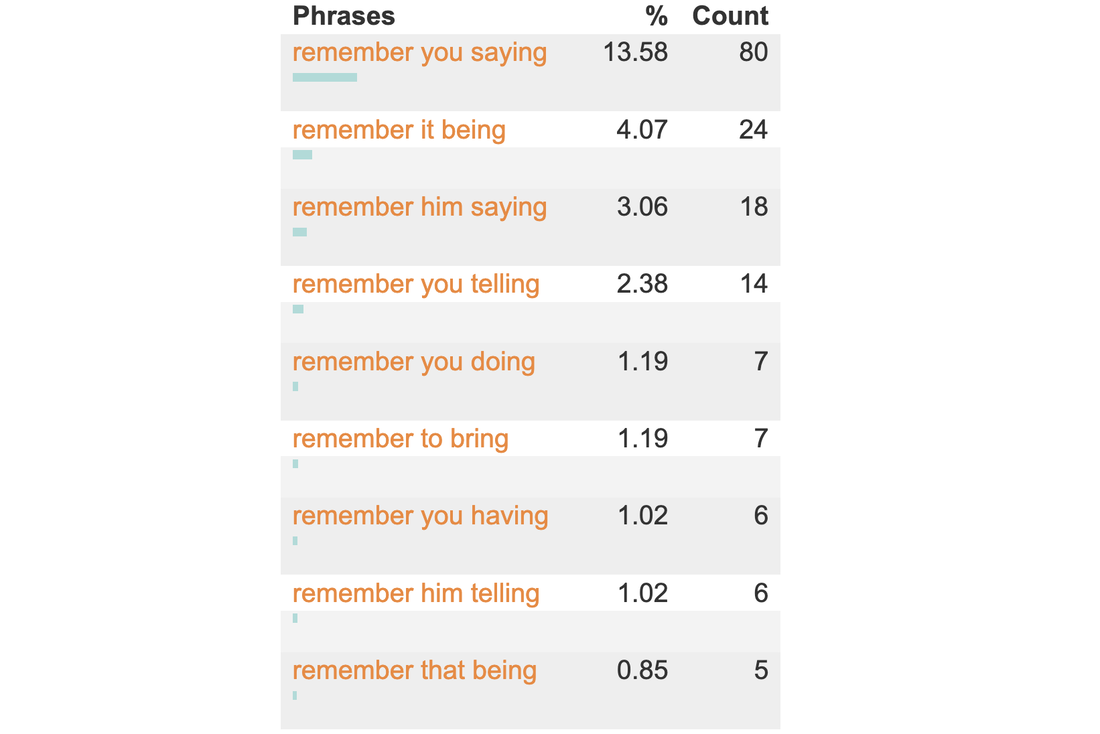

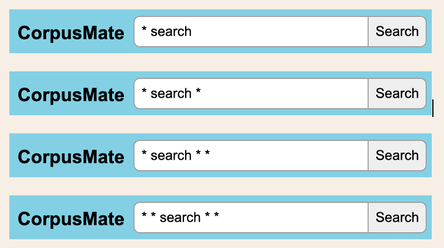

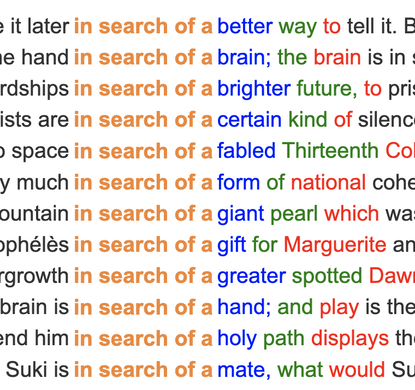

The mighty power of the asteriskFollowing on from my previous post about constellations, in this post I'm looking at the asterisk, which some of my students refer to as a star. I admit that that's a pretty tenuous connection and I apologise whole-heartedly. But the universe does get a mention here, so bear with me. I'm drafting a vocabulary workbook at the moment, or should I say yet another vocabulary workbook. In this one, the students are often tasked with discovering how words work in grammar patterns. They mainly use CorpusMate. This is quite a new, free, open-access and superfast corpus tool that was designed by Peter Croswaithe and programmed by Vit Baisa, who also programmed my VersaText and was instrumental in the development of SkELL. The CorpusMate corpus does not have part of speech tagging, which means that you can't search for a pattern such as Verb + noun + v-ing and there are hundreds of verbs in English that function in this pattern, e.g. remember, picture, catch, tolerate, leave. There are not only hundreds of words, but there are also hundreds of patterns that nouns, verbs and adjectives function in. My current vocabulary book revolves around the COBUILD grammar pattern reference books from the late 1990s. In fact, I wrote my masters dissertation on the grammar patterns of the verbs in the then new Academic Wordlist (2000) that Averil Coxhead had created for her masters dissertation. It is always interesting to see how much can be gleaned about the grammar pattern of a word without part of speech tags. The asterisk is mighty. In fact, it holds the secret to the meaning of life, the universe and everything. Read on! A supercomputer called Deep Thought was asked what the meaning of life, the universe and everything was. It calculated that it was 42. See the announcement in this extract from the film. Douglas Adams, the author of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, the cult 1979 novel from which this comes, always claimed that he chose the number 42 randomly. But 42 is the ASCII code for the asterisk, which in computer searches means anything and everything. Did Deep Thought calculate that the meaning of life, the universe and everything is anything and everything? This search uses two asterisks. The first has spaces before and after it, which makes the program search the corpus for all of the words in between the items to the left and the right of it. The second asterisk is used with a dot and is attached to ing. Dot-star, as my students call it. This makes the program search for words ending with ing. While this might include words such as thing and during, the fact is that the -ing word that follows remember followed by another word tends to be an -ing verb. This is the reality of pattern grammar. Click this link to see the first 250 of the 589 results of this search. This data is automatically sorted so that this pattern in the use of remember can be gleaned. To make these patterns even more visible and student friendly, clicking on the Pattern finder button generates a tidy table. Here are the top nine entries in that table. As mentioned, Verb + noun + -ing is one of hundreds of grammar patterns of words that the COBUILD team uncovered. They were not the first to identify this or many other patterns, but they were able to demonstrate with large corpora the semantic relationships between words that function in the same pattern. This means that the words in a grammar pattern are related in meaning. Important and interesting. Chunks Now back to our mighty asterisk! With queries such as these, you can find the frequent chunks that a target word is used in. The concordance extract below shows some things that people are "in search of a". I'm hoping that a vocabulary workbook that has students learning about the patterns that words function in and the words that go in these patterns through tasking them with discovering these properties of words for themselves using CorpusMate and other tools will be a stimulating voyage of discovery which will add a layer of systematicity to their vocabulary study which will in turn lead to them using words with more confidence and fewer hesitations. Think fluency. They might become stars themselves!

Reach for the stars and draw a constellation. Happy new year!How often have you seen claims like these?

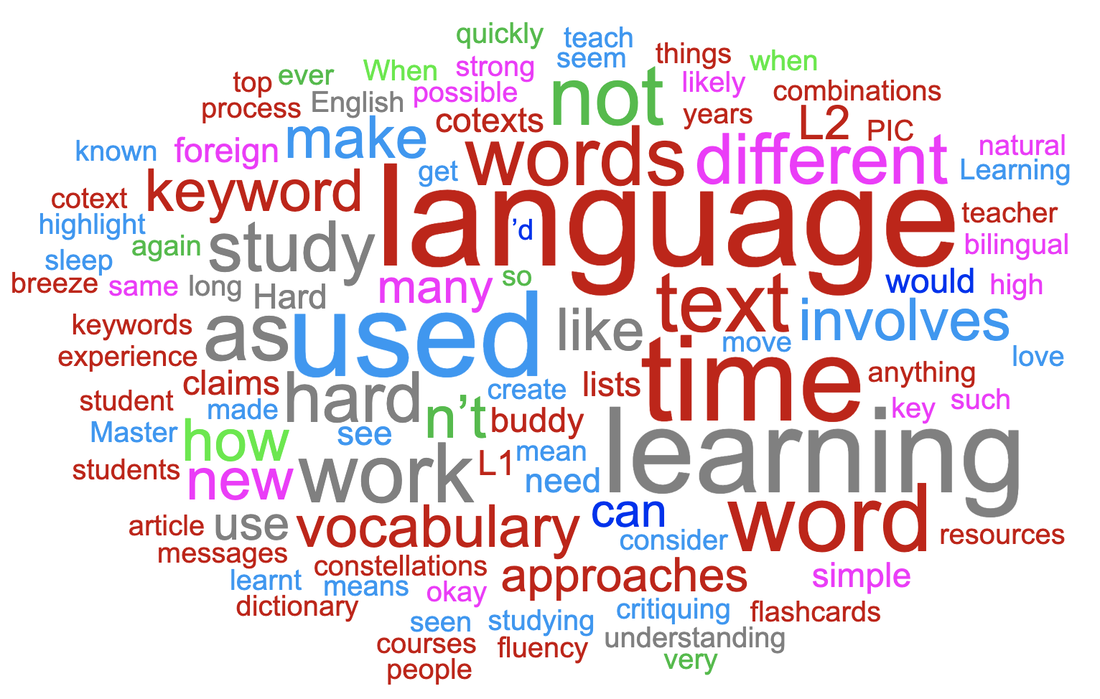

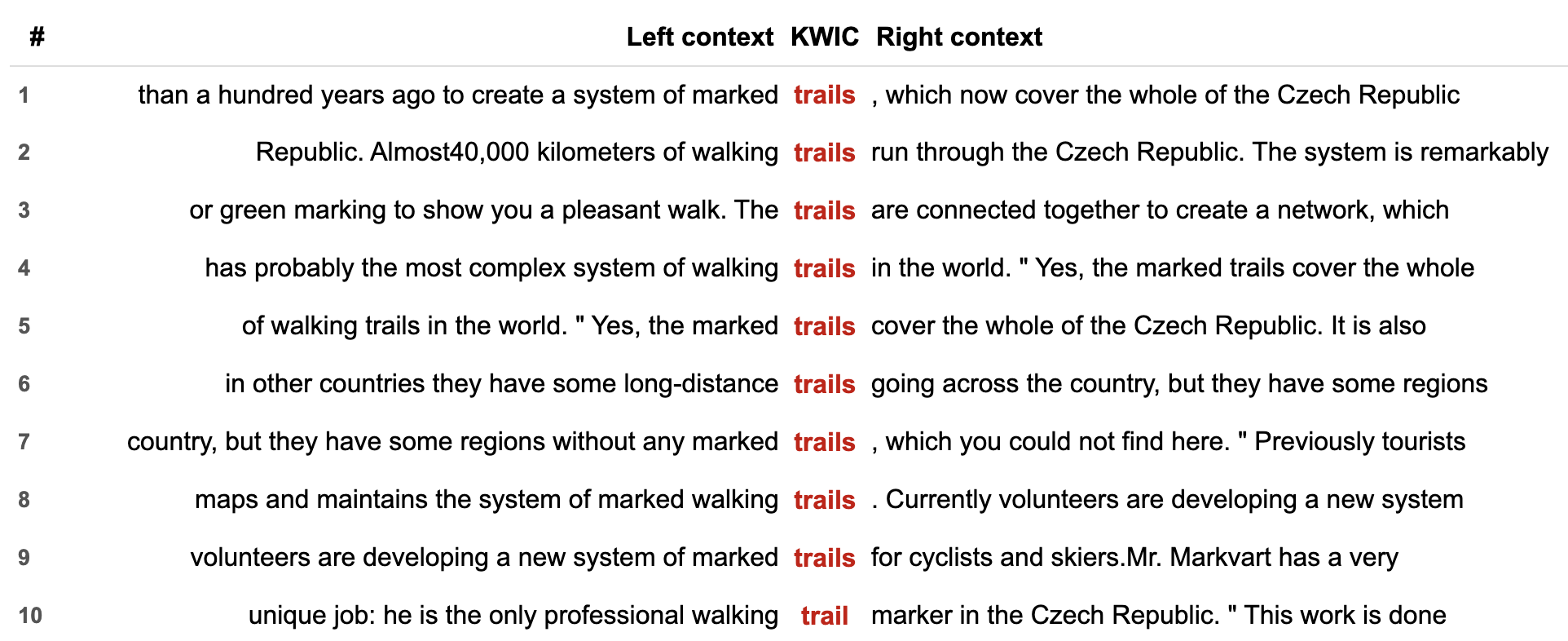

Who would make such claims? Certainly not someone who has achieved a high level of competence in a foreign language. As an eternal language student, and a language teacher and a teacher of teachers, I am pretty certain that you and I have worked hard to get to where we are in our foreign languages. It was not effortless, it wasn’t a breeze and no progress was made while we were asleep. I was so desperate to improve my vocabulary, that I used to sleep with my dictionary under my pillow. No I didn’t, but that is the impression you get from some of these slogans. Learning a language is hard work and there ain’t nothin’ wrong with hard work. Do not confuse hard work with hard labour. Hard doesn’t mean boring and monotonous and it doesn’t mean frustrating and unrewarding. 100 lemmas from this blog post, thank you VersaText. The hard work we do when learning a language involves planning, monitoring and revising. It involves understanding what we are learning, which in turn involves connecting what we already know with what is new to us. Hard work involves practising what we have learnt so that it becomes automatic. Hard work involves using our time efficiently, choosing approaches that work for us. This requires us to assess or critique the approaches to language study that are introduced to us if we are fortunate enough to have various approaches. It is worth reflecting on how many different things we are learning while studying – the learning affordances of an activity. For example, if we are learning a set of words with their first language equivalents, whether in written lists, on paper or electronic flashcards, in a computer game or being tested by our study buddy, the only connection we make is between the L1 and L2 word. We do not learn how the word is used. This leads us to assume that the L2 word is used in the same way as it used in L1 and this is okay when it works. It is not okay the rest of the time. This assumption is referred to by psycholinguists as the semantic equivalence hypothesis (Ijaz 1986, Ringbom 2007), Another issue with learning L1 - L2 pairs is the mental processing of the L2 word: what is your mind doing whilst trying to remember a word? Lower order thinking does not make for a rich learning experience. When we are critiquing our approaches to vocabulary study, we need to consider how many different things we are learning at the same time, a.ka. the affordances. When we study the vocabulary of a text in a text, we see how keywords are used differently each time it is used. Their different uses create different messages which means that the author is telling us something new about the keyword each time it is used. These different messages involve different words, which means we can make a diagram of a keyword as it is used in a text. I call these diagrams Word Constellations. Word constellation from the Czech Walking Trails article (Veselá) We can identify a key word and highlight all of its occurrences in the text, then highlight the words that are used with it. I prefer to do this with VersaText because it is easy to see the left and right cotexts of keywords in a concordance. You can do this with at least several key words in the text. Concordance of trails in said article created in VersaText In critiquing this approach, we need to consider how much was learnt during the time spent. Did the knowledge gained empower us to use the keyword and its cotextual words better than learning such combinations from flashcards or bilingual lists? Did we meet any combinations of words that were new and useful? Did we have to check our dictionary for anything? Did we notice anything about the distribution of the keyword through the text? Did the process heighten our understanding of the text? Did drawing the word constellations feel like a strong learning experience? Was it an enjoyable process? Can we imagine many of these in our vocabulary notebook? Are we likely to refer to them again? And again? Once we have a keyword in its multiple cotexts, we can use these as the bases of our own sentences. We might like to use them to form questions to discuss with our study buddy or our favourite AI tool. Here are some simple examples of a chat with Perplexity.ai. I'm a B1 student of English. Will you be my study buddy today? Of course! I'd be happy to help you with your English studies. Are Czech walking trails a complex system? Are they connected together? Do they run through the whole country? Is this time-consuming? Is it a good use of our time? Are we having strong learning experiences? Are connections forming in our minds that have a high chance of becoming permanent? I used bilingual lists for many years, long after I needed to. I think that if I were to start another foreign language, I would need them as a beginner. But applying what I have actually known for a long time, I would move as quickly as possible to studying words with their natural cotexts. It is possible that people who make claims like those at the top of this article teach vocabulary in cotext, but from the courses and resources that I have seen over the years, it does not seem very likely. If you or your students ever create word constellations, I’d love to see them. And I love to know what the process led to. References

Ijaz, I. H. (1986). Linguistic and cognitive determinants of lexical acquisition in a second language. Language Learning, 36(4): 401-451 Ringbom, H. (2007). Cross-linguistic similarity in foreign language learning (Vol. 21). Multilingual Matters. Veselá, Z. (2003) Czech Republic’s unrivalled system of marked walking trails. Radio Prague International, 5.12.2003. |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|