The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

Reach for the stars and draw a constellation. Happy new year!How often have you seen claims like these?

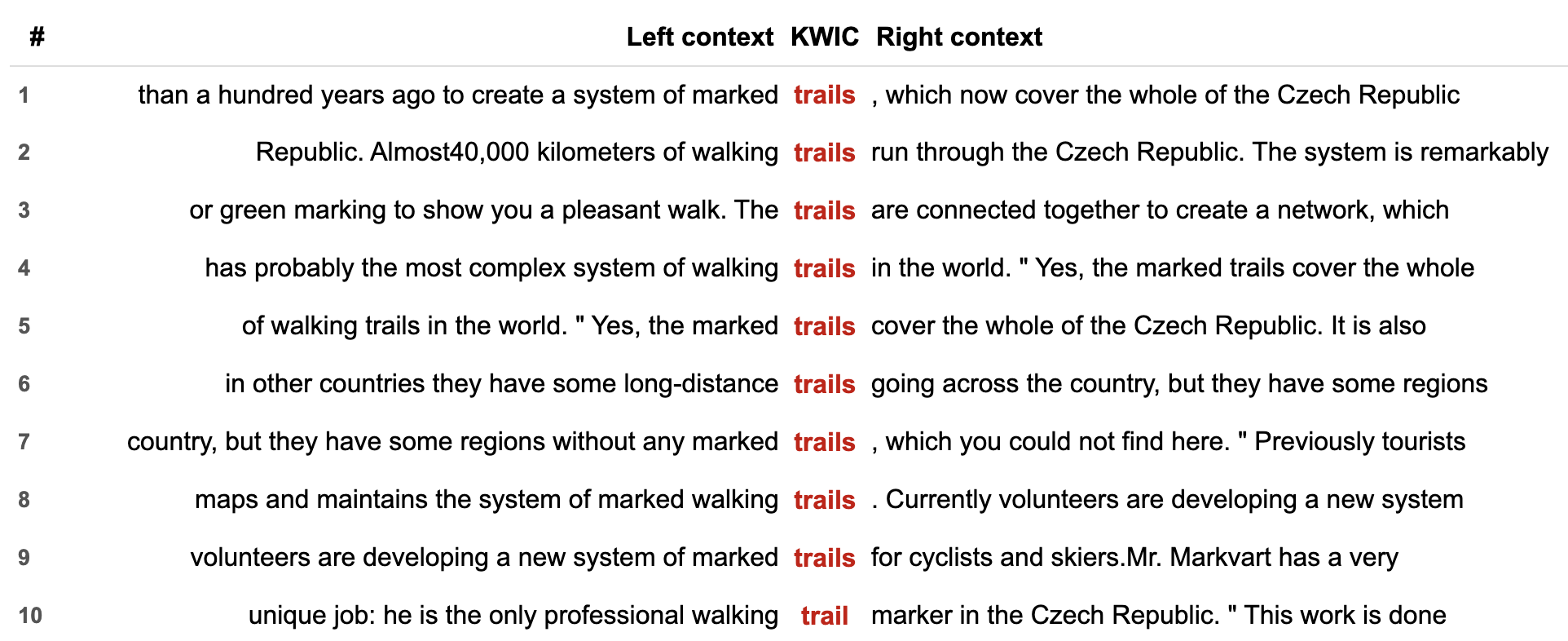

Who would make such claims? Certainly not someone who has achieved a high level of competence in a foreign language. As an eternal language student, and a language teacher and a teacher of teachers, I am pretty certain that you and I have worked hard to get to where we are in our foreign languages. It was not effortless, it wasn’t a breeze and no progress was made while we were asleep. I was so desperate to improve my vocabulary, that I used to sleep with my dictionary under my pillow. No I didn’t, but that is the impression you get from some of these slogans. Learning a language is hard work and there ain’t nothin’ wrong with hard work. Do not confuse hard work with hard labour. Hard doesn’t mean boring and monotonous and it doesn’t mean frustrating and unrewarding. 100 lemmas from this blog post, thank you VersaText. The hard work we do when learning a language involves planning, monitoring and revising. It involves understanding what we are learning, which in turn involves connecting what we already know with what is new to us. Hard work involves practising what we have learnt so that it becomes automatic. Hard work involves using our time efficiently, choosing approaches that work for us. This requires us to assess or critique the approaches to language study that are introduced to us if we are fortunate enough to have various approaches. It is worth reflecting on how many different things we are learning while studying – the learning affordances of an activity. For example, if we are learning a set of words with their first language equivalents, whether in written lists, on paper or electronic flashcards, in a computer game or being tested by our study buddy, the only connection we make is between the L1 and L2 word. We do not learn how the word is used. This leads us to assume that the L2 word is used in the same way as it used in L1 and this is okay when it works. It is not okay the rest of the time. This assumption is referred to by psycholinguists as the semantic equivalence hypothesis (Ijaz 1986, Ringbom 2007), Another issue with learning L1 - L2 pairs is the mental processing of the L2 word: what is your mind doing whilst trying to remember a word? Lower order thinking does not make for a rich learning experience. When we are critiquing our approaches to vocabulary study, we need to consider how many different things we are learning at the same time, a.ka. the affordances. When we study the vocabulary of a text in a text, we see how keywords are used differently each time it is used. Their different uses create different messages which means that the author is telling us something new about the keyword each time it is used. These different messages involve different words, which means we can make a diagram of a keyword as it is used in a text. I call these diagrams Word Constellations. Word constellation from the Czech Walking Trails article (Veselá) We can identify a key word and highlight all of its occurrences in the text, then highlight the words that are used with it. I prefer to do this with VersaText because it is easy to see the left and right cotexts of keywords in a concordance. You can do this with at least several key words in the text. Concordance of trails in said article created in VersaText In critiquing this approach, we need to consider how much was learnt during the time spent. Did the knowledge gained empower us to use the keyword and its cotextual words better than learning such combinations from flashcards or bilingual lists? Did we meet any combinations of words that were new and useful? Did we have to check our dictionary for anything? Did we notice anything about the distribution of the keyword through the text? Did the process heighten our understanding of the text? Did drawing the word constellations feel like a strong learning experience? Was it an enjoyable process? Can we imagine many of these in our vocabulary notebook? Are we likely to refer to them again? And again? Once we have a keyword in its multiple cotexts, we can use these as the bases of our own sentences. We might like to use them to form questions to discuss with our study buddy or our favourite AI tool. Here are some simple examples of a chat with Perplexity.ai. I'm a B1 student of English. Will you be my study buddy today? Of course! I'd be happy to help you with your English studies. Are Czech walking trails a complex system? Are they connected together? Do they run through the whole country? Is this time-consuming? Is it a good use of our time? Are we having strong learning experiences? Are connections forming in our minds that have a high chance of becoming permanent? I used bilingual lists for many years, long after I needed to. I think that if I were to start another foreign language, I would need them as a beginner. But applying what I have actually known for a long time, I would move as quickly as possible to studying words with their natural cotexts. It is possible that people who make claims like those at the top of this article teach vocabulary in cotext, but from the courses and resources that I have seen over the years, it does not seem very likely. If you or your students ever create word constellations, I’d love to see them. And I love to know what the process led to. References

Ijaz, I. H. (1986). Linguistic and cognitive determinants of lexical acquisition in a second language. Language Learning, 36(4): 401-451 Ringbom, H. (2007). Cross-linguistic similarity in foreign language learning (Vol. 21). Multilingual Matters. Veselá, Z. (2003) Czech Republic’s unrivalled system of marked walking trails. Radio Prague International, 5.12.2003.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|