The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

The undersung "and" A sign seen recently in Tashkent. I was adding a little section on fuzzy and fuzziness to my #AfterIELTS course book last week – it is currently on p.72 but that may change between now and its imminent publication. The word fuzzy sounds about as academic as chunk, yet both are revered linguistic concepts. Anyway, whilst writing about fuzzy, I was reminded of the “and” relationship that conspicuously appears in most #wordsketches of most words. Without an awareness of this mighty relationship, however, it is easily overlooked. Conspicuous is it not.

Our fuzzy examples, however, are properties of the word. Make a word sketch for pretty much any noun, verb, adjective, or adverb in the English language and you will find words that and links it with. The more arcane the word, the more arcane the partners. See arcane, for example. Search for words that are in a text you are studying or on a word list you are working with. Explore the "and" relationship by clicking on a word to see it in sentence examples. For example, in the "and" relationship of class, we see among others:

Clicking on category shows 40 sentences related to categorisation. Once again, this represents the way this topic is written and spoken about. Remember that we do not need to read and grasp the sentence examples that corpus searches yield. A concordance page is not a text – it is a source of language data that we skim and scan to identify patterns of normal usage from which we learn how the language works so that our use of the foreign language approximates that of the many native speakers whose output has turned up in the corpus. The "and" pattern, connecting two words of the same part of speech and with similar semantics, often offers lexical support. Rather than expressing something new, this quasi repetition reinforces the meaning or general impression being communicated. This is particularly noticeable with subjective and emotive words. Look at the "and" relationships of: There is also the matter of word order. Words in these and relationships are usually said in a set order.

As language teachers and speakers of foreign languages, we are always interested in the properties of words. Knowing a word’s patterns of normal usage is key to using words as native speakers do. And the confidence that emerges from this knowledge impacts on fluency.

0 Comments

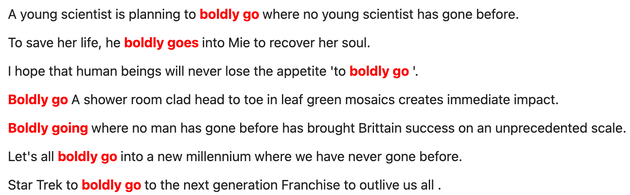

Snowclones adriftIt is a truth universally acknowledged, that a university student in possession of a strong academic vocabulary will be well on the way to toughing out their studies, for we know that when the going gets tough, the tough rush headlong into their studies and boldly go where no student has gone before. And other such exploitations of well-known expressions. You can see more examples of them in the SkELL corpus. And when you do explore them in SkELL, you can read the full sentences and make a wide range of observations. You can discover their original forms and observe how various people have exploited them. And talked about them. Remember that corpora generally consist of thousands of texts created by different individuals and a search provides a sample of the target word or structure. Because SkELL’s corpus is drawn from the internet, you can copy a sentence and Google it to see it in its source text and consider the author’s motivation for using it. You can consider the genre and register of the text: it is unlikely that they would be used in academic papers or in formal conversations. As you have probably heard, Eskimos have 17 words for snow, far more than any other language. This claim is as fatuous as the Great Wall of China being the only man-made object visible from space. And both of these statements are also snowclones, the term used for these linguistic exploitations. I have it on good authority (Wikipedia) that the term was coined by Glen Whitman, economics professor, in 2004, and the linguist, Geoffrey Pullum, endorsed it. Whitman’s inspiration for the term was the fatuous Eskimoan snow claim. Here are a few more snowclones that I have collected over the years. They have various origins and standard uses in English, but all are variously exploited as snowclones.

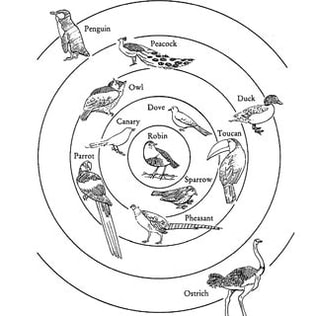

Like all linguistic phenomena, snowclones have been in existence much longer than the term coined to describe them. A term endows a phenomenon not only with a certain gravitas but a recognition that it has a set of features that an entity needs to be worthy of the name. If it has all of the required features it is a prototype (Rosch). Eleanor Rosch Most things deviate to some extent from prototypes, but if they have enough of the features in an adequate proportion, they can be thus labelled. The beloved example of semanticists is birds: which features of pigeons, eagles, emus, penguins and pterodactyls do they possess to be categorised as birds? Another fine example is the English language: which features of English do spoken Texan, Irish football journalese, and academic written English all possess? This makes for an interesting Venn diagram and it leads to a description of “core” English. A nice activity, by the way! Terms are of much use to language students and misuse impedes their progress. We are all familiar with the misnomers, past tense and past participle. As Michael Lewis convincingly conveyed, the past tense is actually about remoteness – in time, in reality, and in social distance. The past participle is a non-finite form and by definition cannot express time. Compound nouns and phrasal verbs are not collocations, and delexical verb structures are neither collocations nor phrasal verbs. Restaurant, bistro and canteen are co-hyponyms, not synonyms. The use of by in passive structures is not a preposition but a particle. When you know the defining features of linguistic phenomena, you can observe them, study them, learn them and use them with confidence. Our English students who also study maths, science, biology, sport, history, geography, literature and the rest, understand very well that their success depends on a profound understanding of the terminology of their field(s). They also know that their professional success demands a professional level of English. Our students deserve as accurate a description of the language as we can provide them. Until you know that snowclones are an identified and labelled feature of the language, you can’t look them up, talk about them, research them, or tag the next one you hear as one. But now you can.

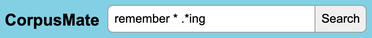

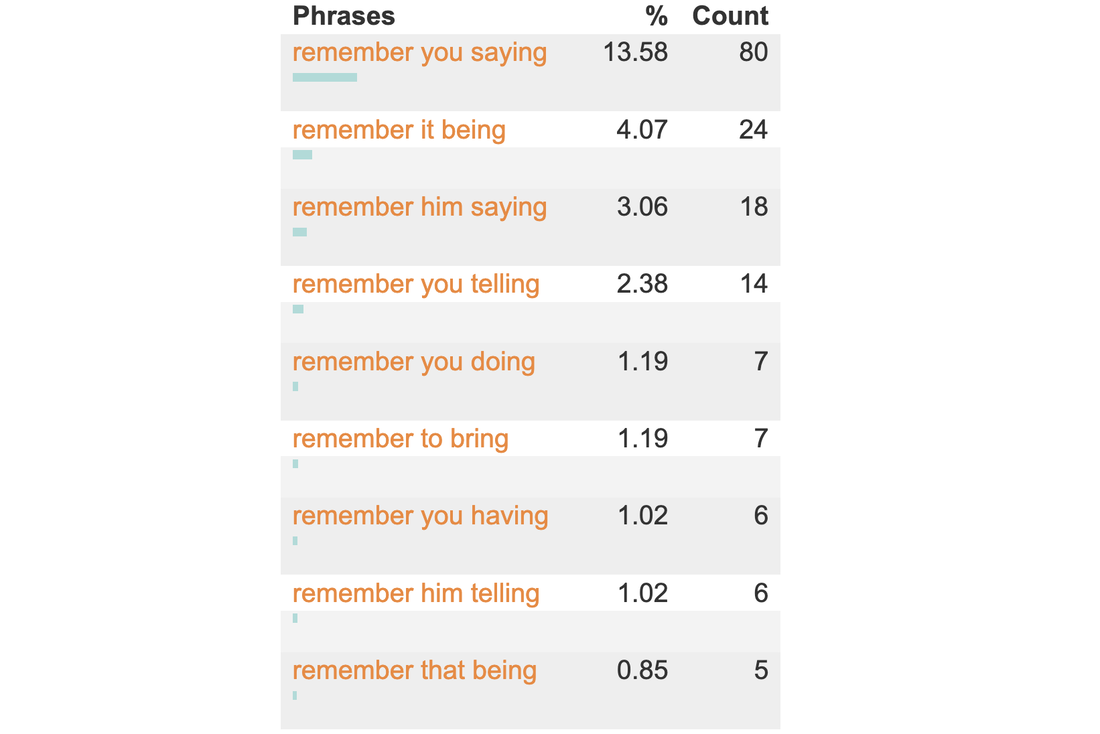

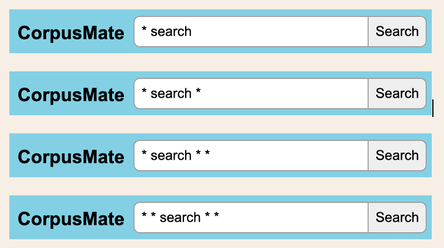

Ask not what students can do for you—ask what you can do for your students! If you have any other favourite, shareworthy snowclones, please add them in the comments below. It would be great to develop this. The mighty power of the asteriskFollowing on from my previous post about constellations, in this post I'm looking at the asterisk, which some of my students refer to as a star. I admit that that's a pretty tenuous connection and I apologise whole-heartedly. But the universe does get a mention here, so bear with me. I'm drafting a vocabulary workbook at the moment, or should I say yet another vocabulary workbook. In this one, the students are often tasked with discovering how words work in grammar patterns. They mainly use CorpusMate. This is quite a new, free, open-access and superfast corpus tool that was designed by Peter Croswaithe and programmed by Vit Baisa, who also programmed my VersaText and was instrumental in the development of SkELL. The CorpusMate corpus does not have part of speech tagging, which means that you can't search for a pattern such as Verb + noun + v-ing and there are hundreds of verbs in English that function in this pattern, e.g. remember, picture, catch, tolerate, leave. There are not only hundreds of words, but there are also hundreds of patterns that nouns, verbs and adjectives function in. My current vocabulary book revolves around the COBUILD grammar pattern reference books from the late 1990s. In fact, I wrote my masters dissertation on the grammar patterns of the verbs in the then new Academic Wordlist (2000) that Averil Coxhead had created for her masters dissertation. It is always interesting to see how much can be gleaned about the grammar pattern of a word without part of speech tags. The asterisk is mighty. In fact, it holds the secret to the meaning of life, the universe and everything. Read on! A supercomputer called Deep Thought was asked what the meaning of life, the universe and everything was. It calculated that it was 42. See the announcement in this extract from the film. Douglas Adams, the author of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, the cult 1979 novel from which this comes, always claimed that he chose the number 42 randomly. But 42 is the ASCII code for the asterisk, which in computer searches means anything and everything. Did Deep Thought calculate that the meaning of life, the universe and everything is anything and everything? This search uses two asterisks. The first has spaces before and after it, which makes the program search the corpus for all of the words in between the items to the left and the right of it. The second asterisk is used with a dot and is attached to ing. Dot-star, as my students call it. This makes the program search for words ending with ing. While this might include words such as thing and during, the fact is that the -ing word that follows remember followed by another word tends to be an -ing verb. This is the reality of pattern grammar. Click this link to see the first 250 of the 589 results of this search. This data is automatically sorted so that this pattern in the use of remember can be gleaned. To make these patterns even more visible and student friendly, clicking on the Pattern finder button generates a tidy table. Here are the top nine entries in that table. As mentioned, Verb + noun + -ing is one of hundreds of grammar patterns of words that the COBUILD team uncovered. They were not the first to identify this or many other patterns, but they were able to demonstrate with large corpora the semantic relationships between words that function in the same pattern. This means that the words in a grammar pattern are related in meaning. Important and interesting. Chunks Now back to our mighty asterisk! With queries such as these, you can find the frequent chunks that a target word is used in. The concordance extract below shows some things that people are "in search of a". I'm hoping that a vocabulary workbook that has students learning about the patterns that words function in and the words that go in these patterns through tasking them with discovering these properties of words for themselves using CorpusMate and other tools will be a stimulating voyage of discovery which will add a layer of systematicity to their vocabulary study which will in turn lead to them using words with more confidence and fewer hesitations. Think fluency. They might become stars themselves!

|

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|