The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

Imperfect passiveI asked ChatGPT for ten passive sentences about the topic of connectionism. As usual, the sentences are bland and inauthentic. But this is one was also problematic.

Consider yourself warned.

1 Comment

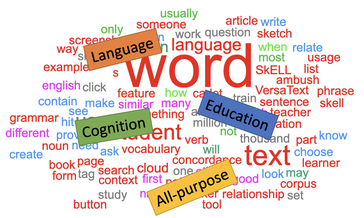

My Tashkent students threw an end of "Vocabulary Strategies" course party. Everyone knows what a word is, right?So, how many words are in this sentence?

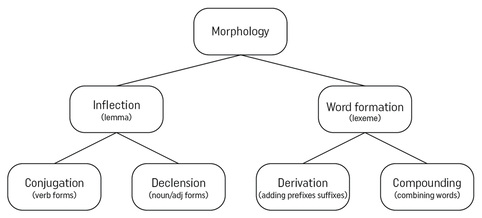

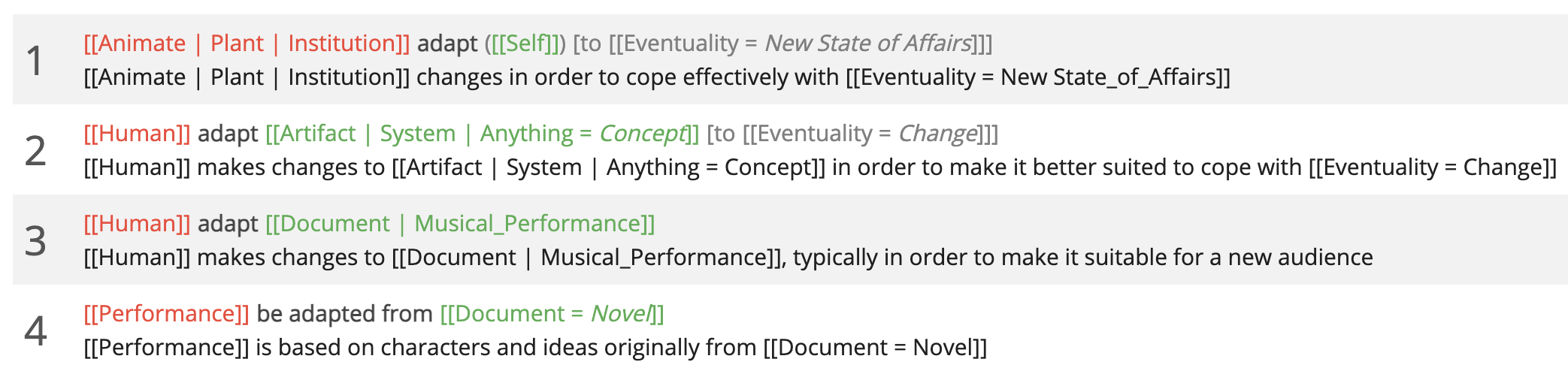

If our definition of a word is a string of letters surrounded by a space or punctuation, it is the same as our computer’s word counts. These are known as orthographic words. We count strike and struck as two word forms of the lemma strike. The other word forms are strikes, striking, stricken. We can distinguish tokens - the number of orthographic words in a sentence or text from types - the number of different word forms. In the next sentence, strike is a noun and a verb. This is variously known as conversion and zero derivation. These are different lemmas – a lemma is the set of word forms of one part of speech. The noun lemma is strike, strikes.

Is flight attendant one word or two? In the next sentence, we have a phrasal verb and a compound adjective.

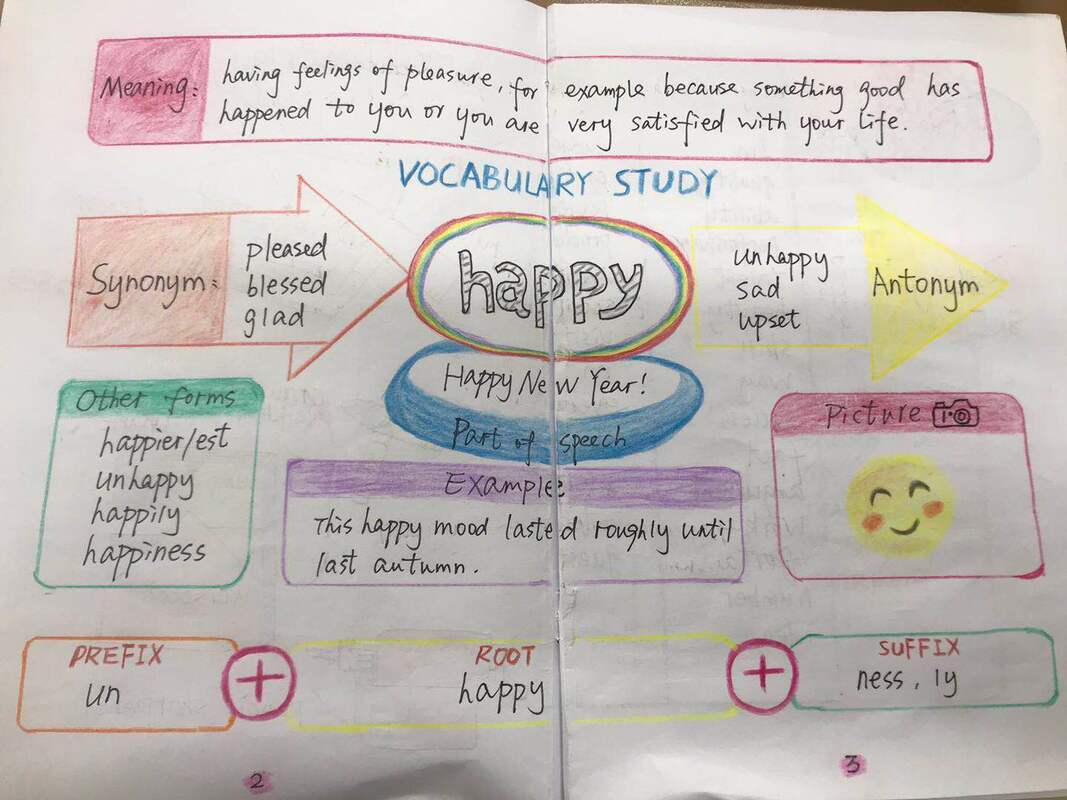

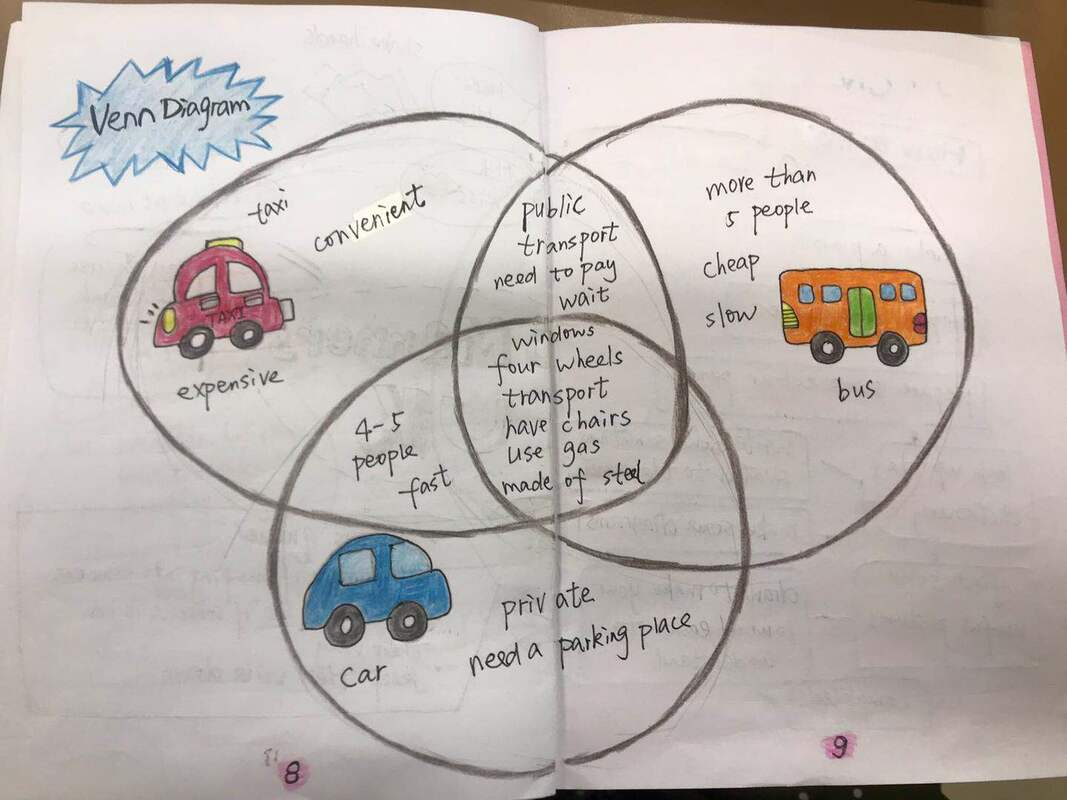

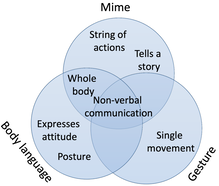

The two orthographic words create these lexemes, i.e. units of meaning. Lexemes can be single words or compounds. Flight attendant is a compound noun, i.e. a lexeme. It is not a collocation because the two words in a collocation retain their individual meanings, e.g. end strike in the second sentence and good approach in the third – best being part of the lemma good. The set of word forms that are formed from a single word are a word family. If you fill the Taxonomy of Morphology with all the word forms of strike, you will have depicted its word family. In addition to the word forms of strike we have already seen, it might include misstrike, overstrike, outstrike, pre-strike, re-strike, strikeout, strike-through, striker, striking (adj), strikingly. Taxonomy of Morphology This may seem like a lot of trouble to go to to answer a question about the number of words in a sentence. In fact, counting words is just a task that draws attention to the issue. Having a superior conceptual grasp of “word” allows students to complete the Taxonomy of Morphology for any lexical items they are studying. Ideally they would observe them whilst reading, listening and watching and add them to their stunningly visual or visually stunning vocabulary notebooks. This would be the impetus for seeking out more word forms of a target word. Halliday considered the term lexical item less indeterminate than the folk-definition of word as he called it. Our students deserve more than the folk definition. They don’t have folk definitions of concepts of physics, chemistry, biology, literary devices and other conceptual networks that they study at secondary school and beyond. They don’t even have folk definitions of the passive voice, articles, conditionals, subordinate clauses and other grammatical concepts when learning English. Their knowledge of vocabulary is however profoundly superficial. We are not helping our students develop their active vocabulary if they cannot distinguish a collocation from a compound noun, if they do not know the properties of phrasal verbs and delexical verb structures, if they do not know that the relationship between vehicle, car and sedan is systematic, if they are unaware of the patterned use of prepositions with nouns, verbs and adjectives as comprehensively demonstrated in these two books from COBUILD. If students are to observe the properties of the words that they encounter in their input so that they can use them in their output, they need to know what a word is and what the properties of different types of words are. Students can learn a great deal of language through learning about language, and this in turn equips them to learn. The standard fare of bilingual lists, flash cards and gapfills reside on the bottom rung of Blooms’ Taxonomy, unlike creatively recording their observations of language in use. Every property of a word begets a learning task. When students structure their vocabulary in mind maps, word roses, word constellations, flow charts, Venn diagrams, semantic features tables, word profiles and the rest, they are engaging higher order thinking skills, they are negotiating with classmates, they are using a lot of words that are related to the target words, some of which may be new or being used in new ways, while others are being recycled. Their higher order thinking skills are also being exercised when they annotate vocabulary features of whole texts. They can trace the topic trails, the different uses of repeated keywords, the collocations and colligations that the author has used. When the students are engaged in wide reading and observe patterns in the use of key words in CLIL, ESP, EMI or general English projects, they learn their genre and register specific usages. This plays a significant role in acculturating students into the conceptual and linguistic milieu of their field.

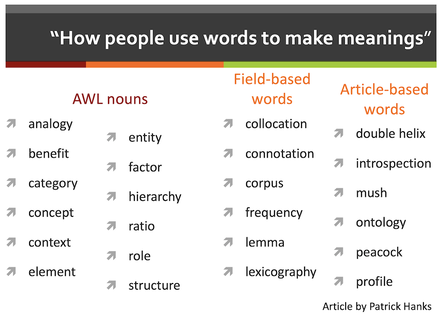

Only students can learn vocabulary. Teachers can teach them about vocabulary and provide them many vocabulary learning strategies, many of which depend on an awareness of lemmas and lexemes, types and tokens, collocation and colligation, word templates and topic trails. And the rest! There is much to be done. Patrick Hanks 1940–2024 |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|