The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

Sort of knowing a wordBack in 1991, I was teaching English on a weekend residential course in old Czechoslovakia. One of the assistants was a student in the arts faculty, where many years later I would find myself head of teacher training. In chatting with this student, she said, but you’re a native speaker – of course you know every word in the English language.

Max’s podcasts are mostly targeted at B1 level, and since his work is partly motivated by Krashen’s comprehensible input hypothesis, I listen for gist. My Russian is well below B1 but I comprehend a lot, and could probably retell the thrust of his monologues in English. This is thanks to my study of Russian, its closeness to Czech and its vocabulary having many English and international words, including those that have Greek and Latin origins. I should mention that there are many false friends between Russian and Czech, my favourite being užasný (amazing, awesome) vs. ужасный (terrible). Each of Max’s podcasts revolve around a single topic, so there is always the general context to help with the gist, but since he only speaks Russian in the podcasts, you have to infer the topic as well. There is no time during the podcast to analyse his use of words so that you might be able to use them in the cotexts that he employs. It is challenging to observe collocation, colligation and chunks on a single listening, and it is not why we listen. So, while the gym has a leg abduction machine, I would say that our brains have a language abduction machine. Abductive reasoning is a form of logical inference that seeks the simplest and most likely conclusion from a set of observations. We do a lot of abducting when our comprehensible input is only just comprehensible.

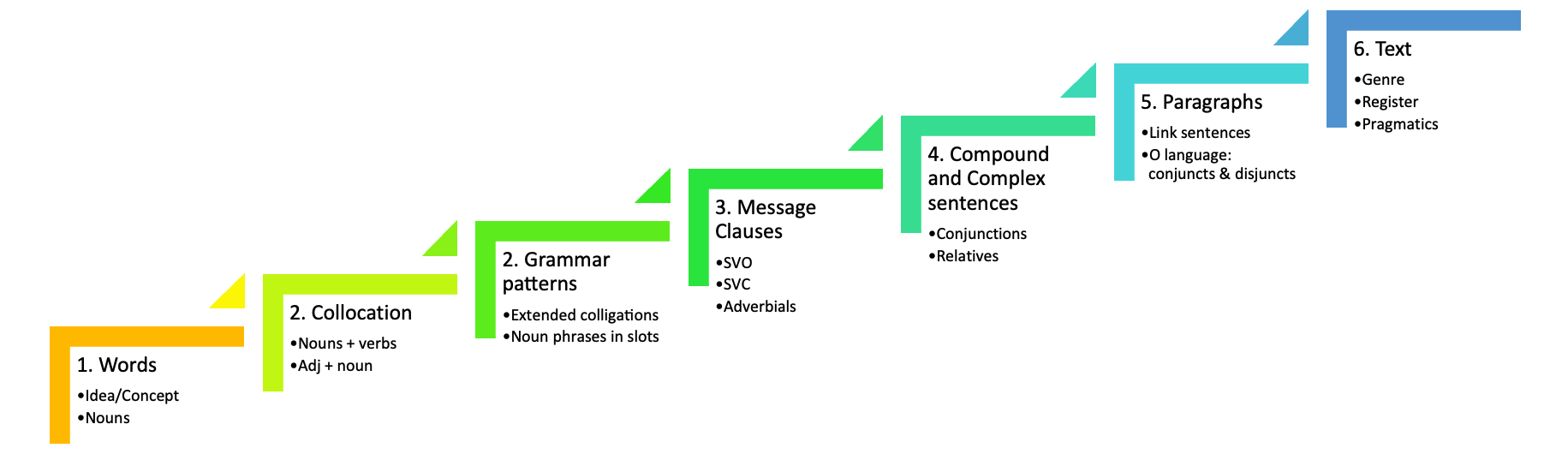

Our word knowledge typically emerges over time in both first and second language acquisition contexts. In FLA our word knowledge mainly accrues through multiple exposure, although we do use dictionaries, chat to friends about new and surprising uses of words. We even read and watch videos about language. In SLA, our word knowledge mainly accrues through structured study, which is both motivated and reinforced by exposure as we read, write, speak and listen. The emergent stages of vocabulary competence can be described thus:

An important application of this continuum is in the revision and recycling of previously studied words. We obviously cannot learn everything there is to know about a word on its first encounter, so this helps temper our expectations. We can also structure the word knowledge that we add in successive revisions. This layering is especially valuable in creating our own vocabulary workbooks and flashcards. I am devoting some pages to flashcards, the use of AI, and this continuum in the book I am writing at the moment. It might have the bumptious title, How to Learn Vocabulary Properly. We’ll see!

0 Comments

One swallow does not summer make

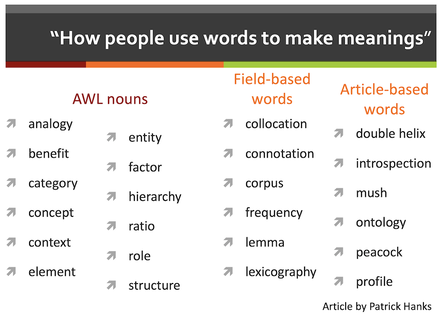

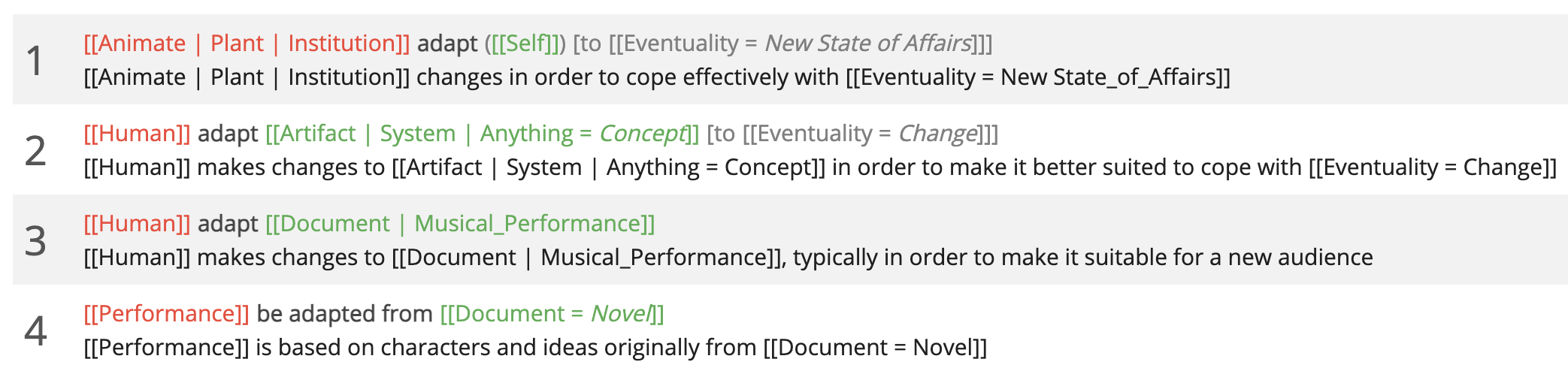

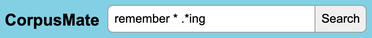

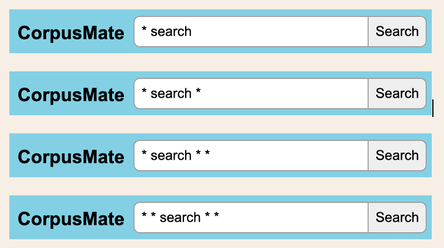

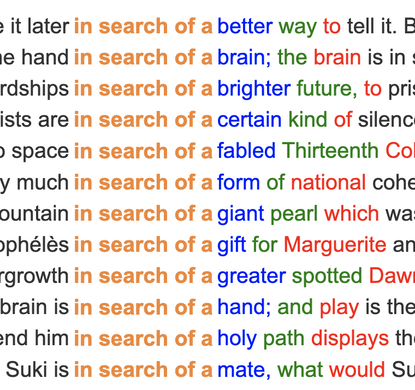

Hoey in fact studied foreign languages so that he could experience the processes of language learning and the practical applications of linguistic and pedagogical theory. When he was observing language in context, that is by reading and listening, he would notice certain collocations but he needed proof of their typicality before he could consider them worth learning. Just because someone has combined a pair of words does not mean that this combination is a typical formulation in the language. The lexicographer, Patrick Hanks (1940–2024) felt the same: Authenticity alone is not enough. Evidence of conventionality is also needed (2013:5). Some years before these two Englishman made these pronouncements, Aristotle (384–322 BC) observed that one swallow does not a summer make. Other languages have their own version of this proverb, sometimes using quite different metaphors, but all making the same point. In order to ascertain that an observed collocation is natural, typical, characteristic or conventional, it is necessary to hunt it down, and there is no better hunting ground for linguistic features than databases containing large samples of the language, a.k.a corpora. In the second paragraph, Hoey experienced the processes … Is experience a process a typical collocation? This is the data that CorpusMate yields: In the same paragraph, we have the following collocation candidates:

Here is some more data from CorpusMate. In the following example, we have a wildcard which allows for one element to appear between the two words of the collocation. Even in these first 12 of the 59 results, other patterns are evident.  The process of validating your findings through multiple sources or methods is known as triangulation, and it is an essential stage in most research. When we train students to triangulate their linguistic observations, it is quite likely that they are familiar with this process from their other school subjects. This is not just a quantitative observation, i.e. this collocation occurs X times in the corpus. It is qualitative as well: the students observe other elements of the cotext, such as the use of other words and grammar structures that the collocation occurs in. They might also observe contextual features that relate to the genres and registers in which the target structure occurs. They are being trained in task-based linguistics as citizen scientists, engaging their higher order thinking skills as pattern hunters. This metacognitive training is a skill for life that will extend far beyond the life of any language course they are undertaking. Triangulation does not apply only to collocation. Any aspect of language can be explored in this way. You may have noticed the word order in the idiom: does not a summer make. Many people have run with this curious word order and exploited it creatively. It is thus a snowclone. Here are some examples from SkELL. Respect our students' intelligence and equip them to learn language from language. ReferencesCroswaithe, P. & Baisa, V. (2024) A user-friendly corpus tool for disciplinary data-driven learning: Introducing CorpusMate International Journal of Corpus Linguistics.

Hanks, P. (2013) Lexical Analysis: Norms and Exploitations. MIT. Hoey, M. (2000) A world beyond collocation: new perspectives on vocabulary teaching. Teaching Collocation. Further Developments in the Lexical Approach. LTP (ed. Lewis, M.) The undersung "and" A sign seen recently in Tashkent. I was adding a little section on fuzzy and fuzziness to my #AfterIELTS course book last week – it is currently on p.72 but that may change between now and its imminent publication. The word fuzzy sounds about as academic as chunk, yet both are revered linguistic concepts. Anyway, whilst writing about fuzzy, I was reminded of the “and” relationship that conspicuously appears in most #wordsketches of most words. Without an awareness of this mighty relationship, however, it is easily overlooked. Conspicuous is it not.

Our fuzzy examples, however, are properties of the word. Make a word sketch for pretty much any noun, verb, adjective, or adverb in the English language and you will find words that and links it with. The more arcane the word, the more arcane the partners. See arcane, for example. Search for words that are in a text you are studying or on a word list you are working with. Explore the "and" relationship by clicking on a word to see it in sentence examples. For example, in the "and" relationship of class, we see among others:

Clicking on category shows 40 sentences related to categorisation. Once again, this represents the way this topic is written and spoken about. Remember that we do not need to read and grasp the sentence examples that corpus searches yield. A concordance page is not a text – it is a source of language data that we skim and scan to identify patterns of normal usage from which we learn how the language works so that our use of the foreign language approximates that of the many native speakers whose output has turned up in the corpus. The "and" pattern, connecting two words of the same part of speech and with similar semantics, often offers lexical support. Rather than expressing something new, this quasi repetition reinforces the meaning or general impression being communicated. This is particularly noticeable with subjective and emotive words. Look at the "and" relationships of: There is also the matter of word order. Words in these and relationships are usually said in a set order.

As language teachers and speakers of foreign languages, we are always interested in the properties of words. Knowing a word’s patterns of normal usage is key to using words as native speakers do. And the confidence that emerges from this knowledge impacts on fluency. Collocation and VersaTextI had an email from a teacher who loves using my VersaText tool with his students. In addition to the very welcome and rarely received praise for VersaText, he was enquiring into the possibility of adding a collocation feature. As you know, VersaText works with single texts, its slogan being, “learning language from language, one text at a time”, collocations are vanishingly rare. In fact, “vanishingly rare” is a strong collocation in English. Check out the examples in #SkELL.

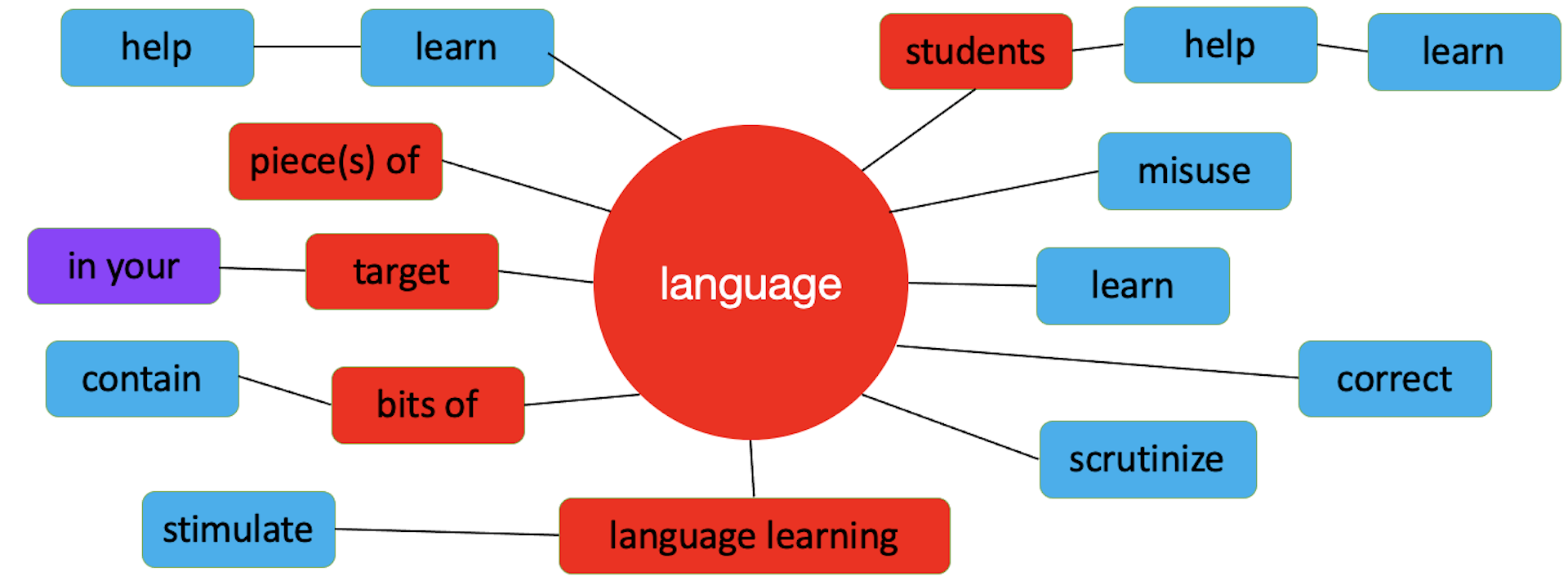

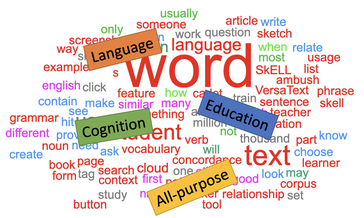

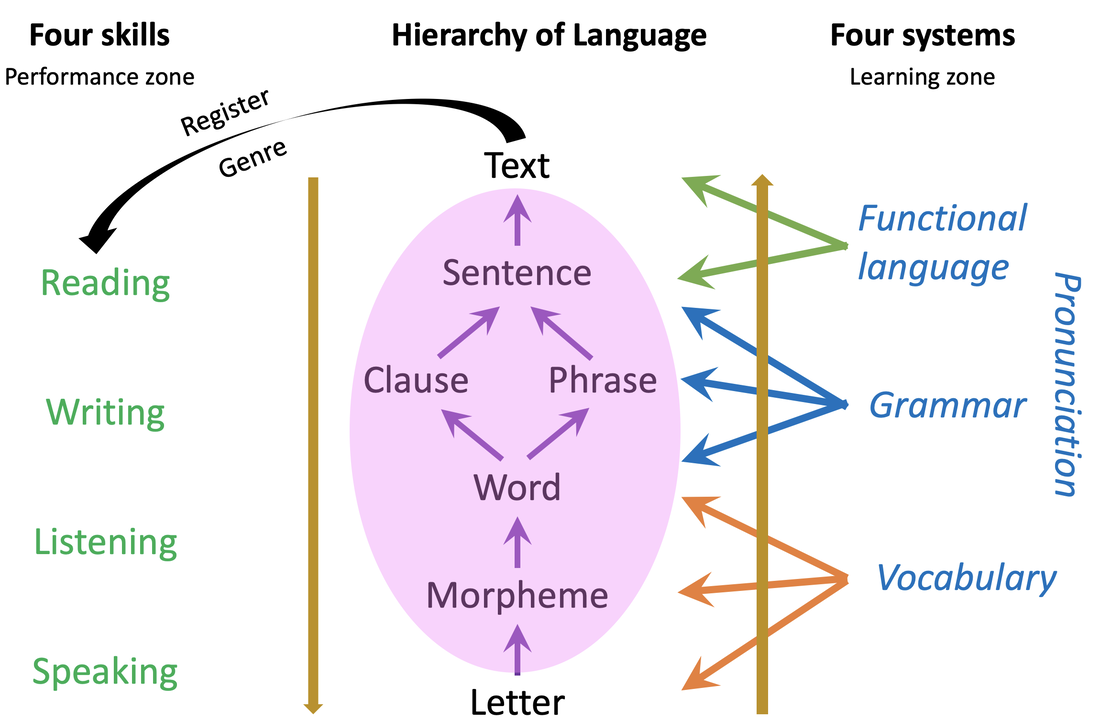

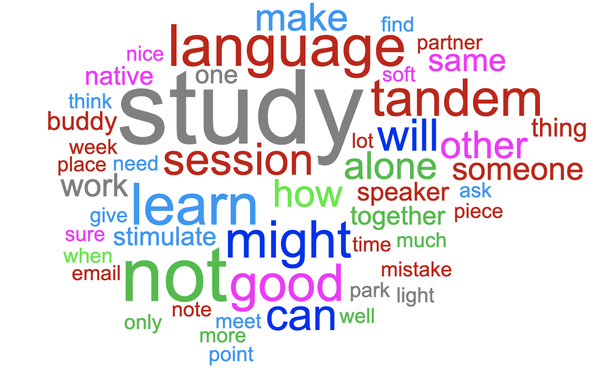

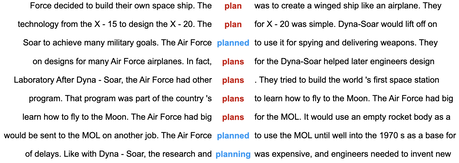

#Collocation is defined variously. First and foremost, collocation consists of two content words of different parts of speech. Compound nouns and adjectives, phrasal and delexical verbs are not collocations. And neither are words that combine with that/ -ing / inf / wh-/prepostions. These are colligations and offer very little choice, if any. You’ve all seen gap fills in coursebooks and exams that test this. Collocation does permit some variation, but within limits of acceptability if you are going to use the patterns of normal usage of the language. One category of definitions of collocation revolves around statistical frequency. These definitions rely on the number of times words occur in close proximity to each other. The verb collocates of trouble, for example, occur frequently within four words before and/or after the noun in SkELL's huge sample of English. Other definitions of collocation are phraseological: cause trouble is the core of a clause, which is the essential structure that creates Messages, which in turn constitutes text. Up the Hierarchy of Language we go! Most key words in most texts collocate with different items because the author is telling us something new about the word. And this is why a collocation tool in VersaText would be by and large redundant. One thing we can be sure of in a text is that the author is not going to repeat the same message repeatedly, again and again, over and over, unless they have some rhetorical reason for doing so. Here is an example. In VersaText’s sample text, Learning Zone (a transcript of a TED Talk), we see that the verb spend is frequently used with time, and with other time words, e.g. minutes, hours, our lives. It occurs 13 times in the text. Time occurs 28 times in the text and is used thus: CTRL F in the browser highlights the nominated word as it occurs in the cotext of the target word. Improve occurs 15 times in the text, each time in a different Message. This is far more typical of words in text than a frequently used collocation like spend time. Go to VersaText, select the Learning Zone text from the list, then click Wordcloud at the top. If you want the lemma of improve, for example, choose the lemma radio button under the word cloud. Click on any word to see its concordance in this text. This motivates many discovery learning tasks for the students. If you want to learn more about studying and teaching English with VersaText, click the Course button at the top of the VersaText pages. My phraseological approach to collocations in single texts is the Word Constellation. See my blog post linked below. This is a word constellation. It is built upon a VersaText concordance of the word language in text about language learning.

My Tashkent students threw an end of "Vocabulary Strategies" course party. Everyone knows what a word is, right?So, how many words are in this sentence?

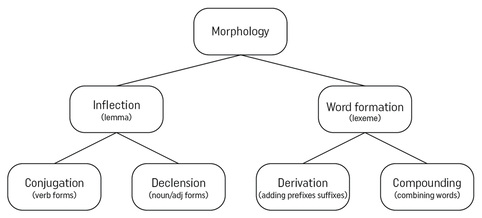

If our definition of a word is a string of letters surrounded by a space or punctuation, it is the same as our computer’s word counts. These are known as orthographic words. We count strike and struck as two word forms of the lemma strike. The other word forms are strikes, striking, stricken. We can distinguish tokens - the number of orthographic words in a sentence or text from types - the number of different word forms. In the next sentence, strike is a noun and a verb. This is variously known as conversion and zero derivation. These are different lemmas – a lemma is the set of word forms of one part of speech. The noun lemma is strike, strikes.

Is flight attendant one word or two? In the next sentence, we have a phrasal verb and a compound adjective.

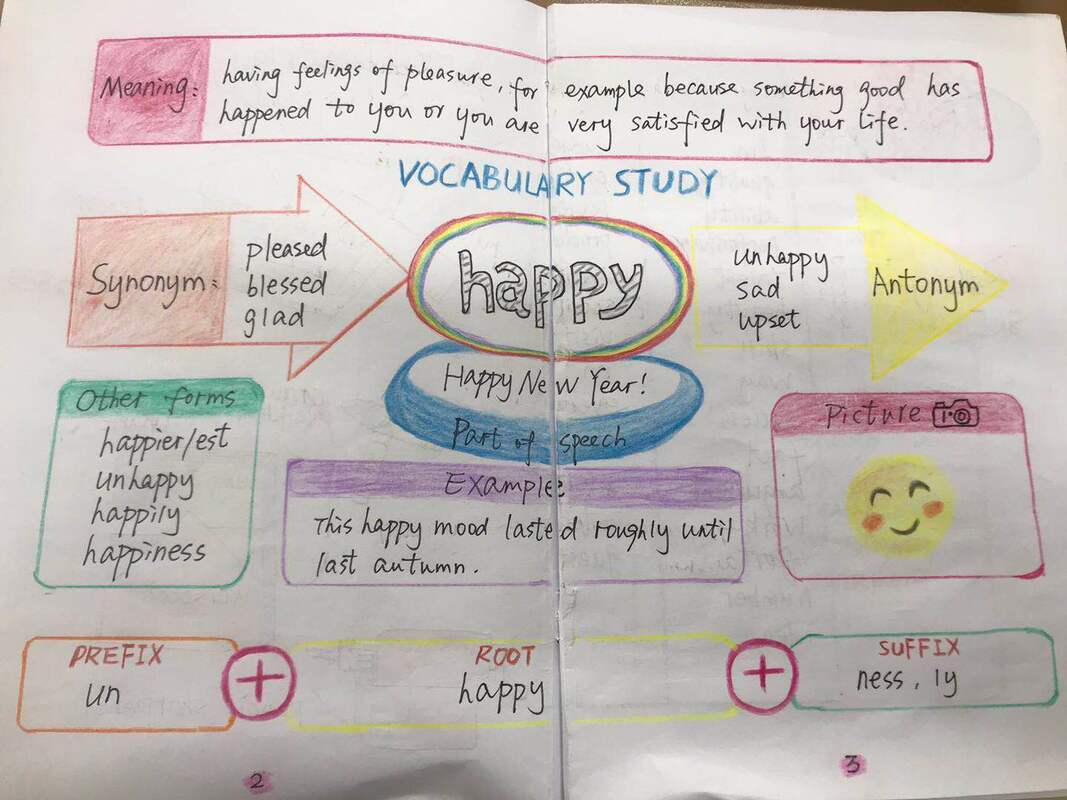

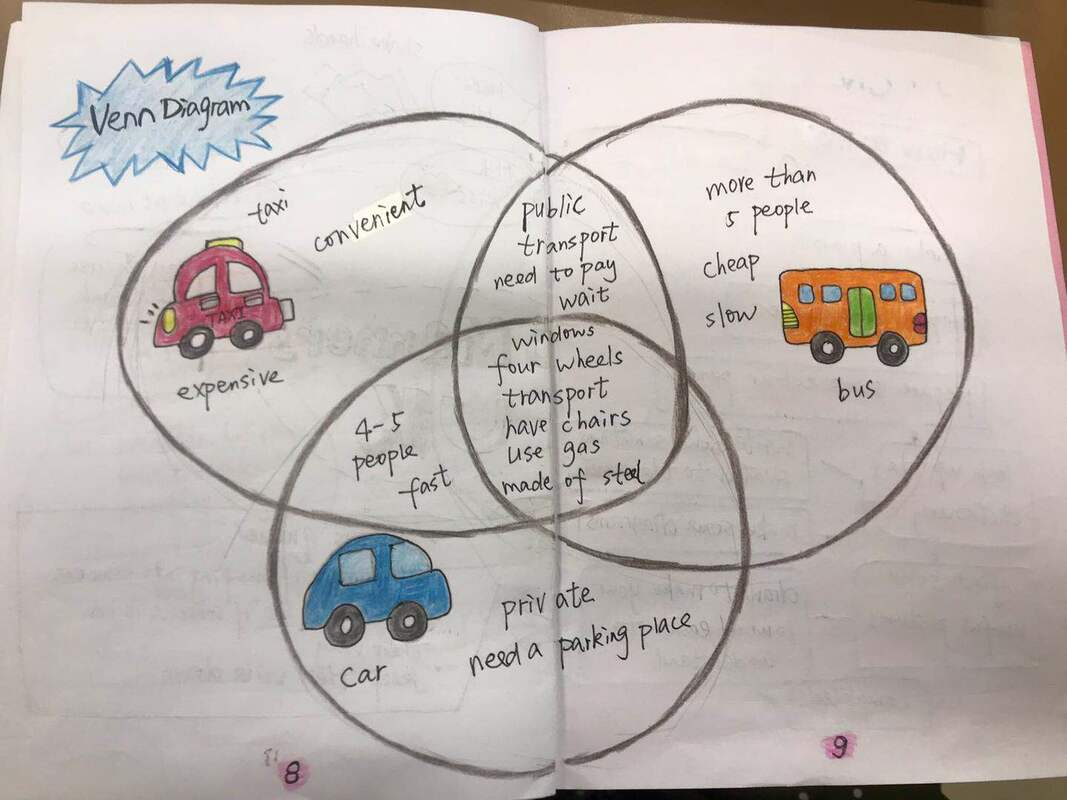

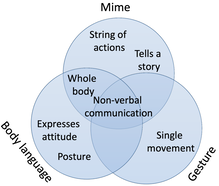

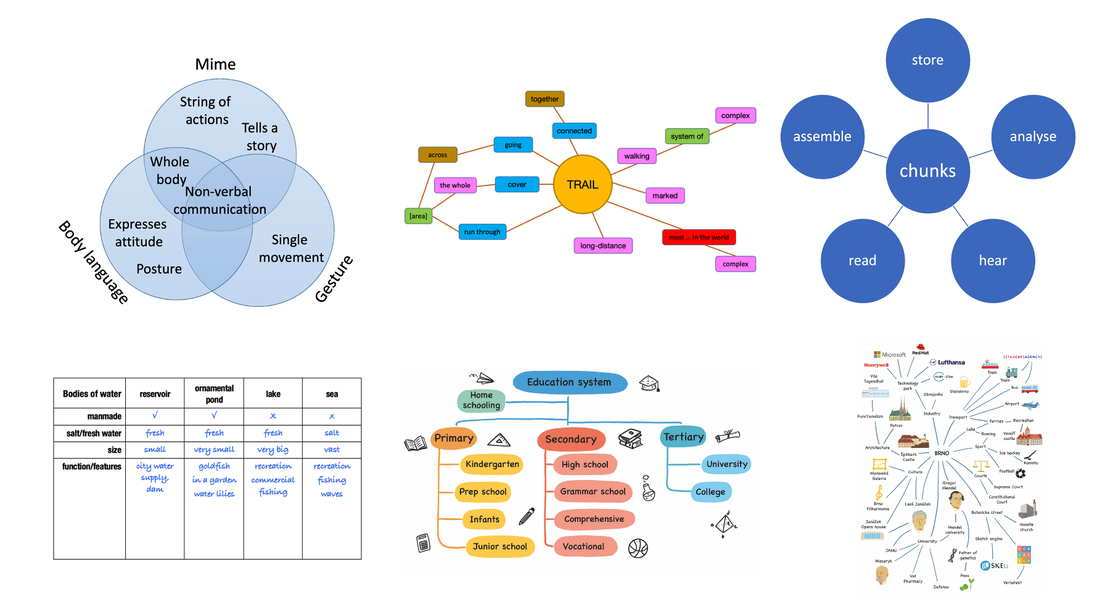

The two orthographic words create these lexemes, i.e. units of meaning. Lexemes can be single words or compounds. Flight attendant is a compound noun, i.e. a lexeme. It is not a collocation because the two words in a collocation retain their individual meanings, e.g. end strike in the second sentence and good approach in the third – best being part of the lemma good. The set of word forms that are formed from a single word are a word family. If you fill the Taxonomy of Morphology with all the word forms of strike, you will have depicted its word family. In addition to the word forms of strike we have already seen, it might include misstrike, overstrike, outstrike, pre-strike, re-strike, strikeout, strike-through, striker, striking (adj), strikingly. Taxonomy of Morphology This may seem like a lot of trouble to go to to answer a question about the number of words in a sentence. In fact, counting words is just a task that draws attention to the issue. Having a superior conceptual grasp of “word” allows students to complete the Taxonomy of Morphology for any lexical items they are studying. Ideally they would observe them whilst reading, listening and watching and add them to their stunningly visual or visually stunning vocabulary notebooks. This would be the impetus for seeking out more word forms of a target word. Halliday considered the term lexical item less indeterminate than the folk-definition of word as he called it. Our students deserve more than the folk definition. They don’t have folk definitions of concepts of physics, chemistry, biology, literary devices and other conceptual networks that they study at secondary school and beyond. They don’t even have folk definitions of the passive voice, articles, conditionals, subordinate clauses and other grammatical concepts when learning English. Their knowledge of vocabulary is however profoundly superficial. We are not helping our students develop their active vocabulary if they cannot distinguish a collocation from a compound noun, if they do not know the properties of phrasal verbs and delexical verb structures, if they do not know that the relationship between vehicle, car and sedan is systematic, if they are unaware of the patterned use of prepositions with nouns, verbs and adjectives as comprehensively demonstrated in these two books from COBUILD. If students are to observe the properties of the words that they encounter in their input so that they can use them in their output, they need to know what a word is and what the properties of different types of words are. Students can learn a great deal of language through learning about language, and this in turn equips them to learn. The standard fare of bilingual lists, flash cards and gapfills reside on the bottom rung of Blooms’ Taxonomy, unlike creatively recording their observations of language in use. Every property of a word begets a learning task. When students structure their vocabulary in mind maps, word roses, word constellations, flow charts, Venn diagrams, semantic features tables, word profiles and the rest, they are engaging higher order thinking skills, they are negotiating with classmates, they are using a lot of words that are related to the target words, some of which may be new or being used in new ways, while others are being recycled. Their higher order thinking skills are also being exercised when they annotate vocabulary features of whole texts. They can trace the topic trails, the different uses of repeated keywords, the collocations and colligations that the author has used. When the students are engaged in wide reading and observe patterns in the use of key words in CLIL, ESP, EMI or general English projects, they learn their genre and register specific usages. This plays a significant role in acculturating students into the conceptual and linguistic milieu of their field.

Only students can learn vocabulary. Teachers can teach them about vocabulary and provide them many vocabulary learning strategies, many of which depend on an awareness of lemmas and lexemes, types and tokens, collocation and colligation, word templates and topic trails. And the rest! There is much to be done. A few issues with traditional vocabulary teachingHaving been engaged in language study for over four decades, made attempts on four foreign languages and witnessed the growth of my first language, English, I can assure you that I have invested a great deal of time into learning vocabulary. Much of it was wasted. Much of it was spent learning useless words in ways that did not teach me how the words work in the target language. Vocabulary learning strategies were not taught. It was simply assumed that students would memorise context-free bilingual lists as if the L2 words worked in the same way as in L1. If I was lucky, my attempts to use the words in sentences and texts were returned bespattered with red ink highlighting collocation and colligation errors in particular. In my experience as a language learner, teacher, trainer and author, I consider the following activities useful but limited:

The reasons I consider these procedures limited:

You can probably think of some counter examples. And so can I. But what I see in contemporary course books does not negate most of the above. Alternatively, we could respect our students' intelligence and creativity.We can task our students with identifying relationships between words and within words, and depict them meaningfully. These examples come from my Versatile Blank Book, which you can read about on this site.

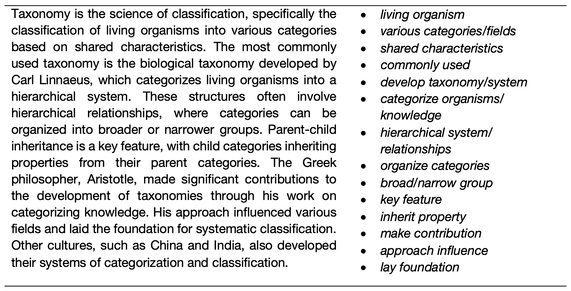

Learning language from language with VersaTextEvery layer of the hierarchy of language can be explored by students in a text. The exploration of Texts as Linguistic Objects (TALO) reveals how an author has used words and word forms, combined them as collocations and colligations, formed phrases and clauses that are linked with metadiscourse chunks to ultimately form texts. This is the bottom-up process that we employ both subconsciously and consciously when we speak and write. As well as being linguistic objects, Texts are also Vehicles of Information (TAVI) which invoke top-down processes as we combine the content of the text with what we know about the world through schemata, general knowledge and our expectations of text types. In this way, readers and listeners are engaged in their own personal knowledge creation. Thirdly, Texts are Springboards for Production (TASP). We respond to texts by combining several texts on the same topic, by critiquing aspects of the text, and by discussing the potential impact of this new knowledge, for example. To put texts under the microscope, VersaText is an open access, web-based resource that allows teachers and students to paste in a single text. The program provides several tools that foster discovery learning. The first tool is the word cloud, which depicts not only the relative frequencies of words in a text, but it colour-codes part of speech. The word cloud is highly customisable: the number of words, the choice of words vs. lemmas, which parts of speech to show. The relative sizes of words in the word cloud illustrate the extent of repetition in a text and repetition is the most commonly used resource to create lexical cohesion in text (Halliday & Hasan, 1976). When you click on a word in the word cloud, it shows a concordance of that word in the text. The concordance lines are in text order, which shows how the meaning of a key word evolves through different cotexts (Hoey, 1991). Inferring the meaning of an unknown word when it is shown in at least several cotexts is a far more realistic expectation than doing so from a single meeting with a word. It is possible to observe the use of articles with the first and subsequent noun references. Other colligation patterns can also be observed, such as the use of that and wh- clauses, and bound prepositions. Collocation, when defined as a frequency phenomenon, is not a pertinent feature of a single text, as a collocation is a unit of meaning that authors do not need to repeat. A phraseological definition of collocation is therefore more appropriate here (Partington, 1998). It is not uncommon for a text to include many verbs that collocate with a key noun. Observing collocation in such authentic contexts is an authentic learning task, as is employing said collocations in TASP. As students observe the key words in a text and their cotexts that create each of the author’s messages or propositions, they are not only engaged in TALO but they are also deepening their TAVI. Engaging such higher order thinking skills respects the intelligence of our students unlike so-called “tasks” such as multiple choice comprehension questions and gap filling. In addition to word clouds and concordances, VersaText provides text statistics including an estimate of a text’s CEFR level. It also shows the percentages of words that are function words, three bands of content words, academic words and text-specific words. It also lists all of these words in these categories in tables which can be used by teachers and students who are especially focused on vocabulary development. The opportunity to put the language of a single text under such a microscope is invaluable to students of CLIL, EMI and ESP, as the texts are models of the language of subjects and fields that the students need to have a productive knowledge of, if they are to be acculturated into their subject disciplines. This is essential for TASP. Feel free to join the VersaText Facebook Group where you can share your experiences and learn from others. ReferencesHalliday, M.A.K. & Hasan, R. (1976) Cohesion in English. Longman

Hoey, M. (1991) Patterns of Lexis in Text. OUP. Johns, T., Davies, F. (1983) Text as a vehicle for information: the classroom use of written texts in teaching reading in a foreign language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 1 (1) Partington, A. (1998) Patterns and Meanings: Using Corpora for English Language Research and Teaching. John Benjamins. Patrick Hanks 1940–2024 |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|