The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

Reach for the stars and draw a constellation.How often have you seen claims like these?

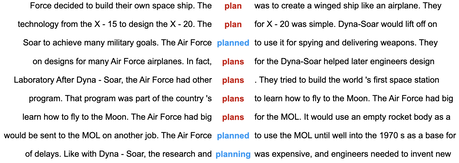

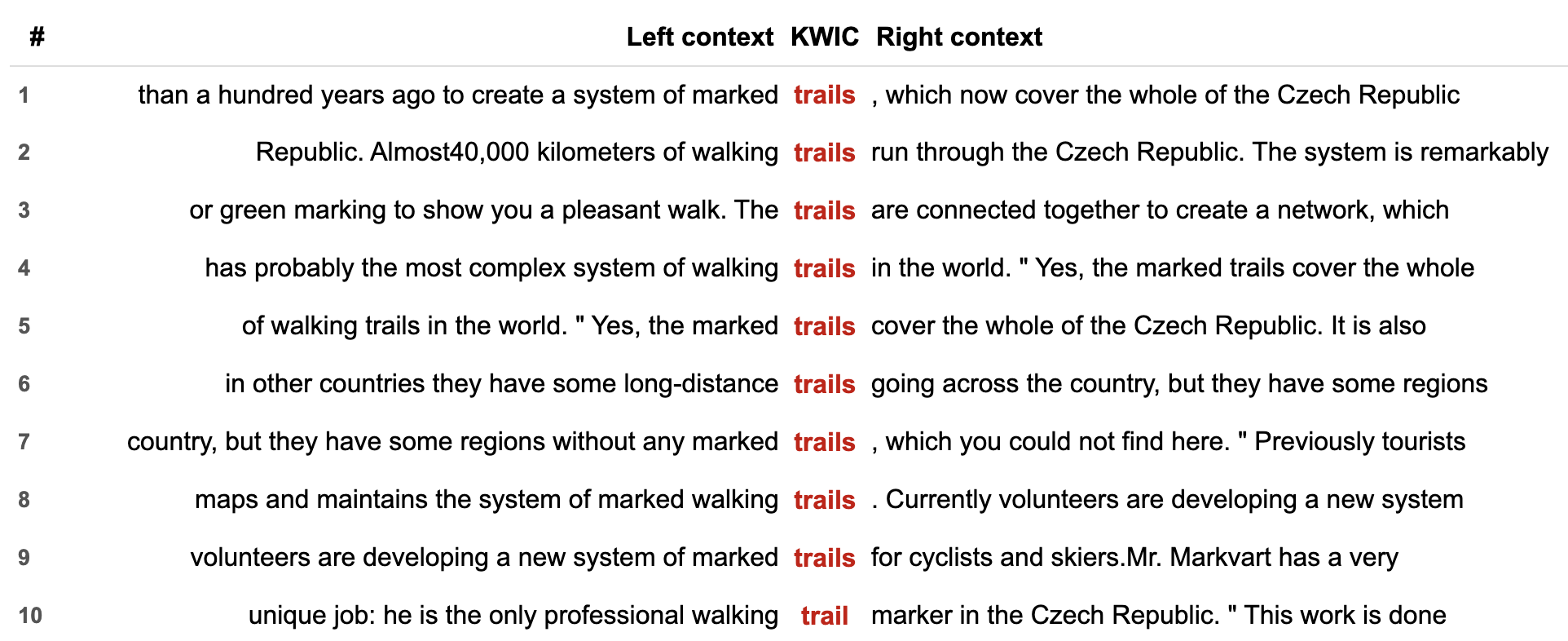

Who would make such claims? Certainly not someone who has achieved a high level of competence in a foreign language. As an eternal language student, and a language teacher and a teacher of teachers, I am pretty certain that you and I have worked hard to get to where we are in our foreign languages. It was not effortless, it wasn’t a breeze and no progress was made while we were asleep. I was so desperate to improve my vocabulary, that I used to sleep with my dictionary under my pillow. No I didn’t, but that is the impression you get from some of these slogans. Learning a language is hard work and there ain’t nothin’ wrong with hard work. Never confuse hard work with hard labour. Hard doesn’t mean boring and monotonous and it doesn’t mean frustrating and unrewarding. The hard work we do when learning a language involves planning, monitoring and revising. It involves understanding what we are learning, which in turn involves connecting what we already know with what is new to us. Hard work involves practising what we have learnt so that it becomes automatic. Hard work involves using our time efficiently, choosing approaches that work for us. This requires us to assess or critique the approaches to language study that are introduced to us if we are fortunate enough to have various approaches. It is worth reflecting on how many different learning experiences we are having while studying – the learning #affordances of an activity. For example, if we are learning a set of English words with their first language equivalents, whether in written lists, on paper or electronic flashcards, in a computer game or being tested by our study buddy, the only connection we make is between the L1 and L2 word. We do not learn how the word is used. This leads us to assume that the L2 word is used in the same way as it used in L1 and this is okay when it works. It is not okay the rest of the time. Psycholinguists refer to this assumption as the semantic equivalence hypothesis (Ijaz 1986, Ringbom 2007). Another issue with learning L1–L2 pairs is the mental processing of the L2 word: what is your mind doing whilst trying to remember a word? Lower order thinking does not make for a rich learning experience. When we are critiquing our approaches to vocabulary study, we need to consider how many different features of words we are learning at the same time. However, when we study the vocabulary of a text in a text, we see how keywords are used differently each time they are used. Yes, their different uses create different messages which means that the author is telling us something new about the keyword each time it is used. These different messages involve different words, which means we can make a diagram of a keyword as it is used in a text. I call these diagrams Word Constellations. We can identify a key word and highlight all of its occurrences in the text, then highlight the words that are used with it. I prefer to do this with #VersaText because it is easy to see the left and right cotexts of keywords in a concordance. You can do this with at least several key words in the text. In critiquing this approach, we need to consider how much the students learnt during the time spent.

If they didn't create a word constellation of a key word in a text, what did they do? How did they spend their time? What learning took place? Once we have a keyword in its multiple cotexts, we can use them as the bases of our own sentences. We might like to use them to form questions to discuss with our study buddy or our favourite AI tool. Here are some simple examples of a chat with Perplexity.ai. Hi. I'm a B1 student of English. Will you be my study buddy today? Of course! I'd be happy to help you with your English studies.

Is this time-consuming? Is it a good use of our time? Are we having strong learning experiences? Are connections forming in our minds that have a high chance of becoming permanent? I used bilingual lists for many years, long after I needed to. I think that if I were to start another foreign language, I would need them as a beginner. But applying what I have actually known for a long time, I would move as quickly as possible to studying words with their natural cotexts. It may be the case that people who make claims like those at the top of this article do actually teach vocabulary in cotext, but from the courses and resources that I have seen over the years, this does not seem very likely. If you or your students ever create word constellations, I’d love to see them. And I would love to know what the process led to. Feel free to join the VersaText Facebook Group where you can share your experiences and learn from others. ReferencesIjaz, I. H. (1986). Linguistic and cognitive determinants of lexical acquisition in a second language. Language Learning, 36(4): 401-451

Ringbom, H. (2007). Cross-linguistic similarity in foreign language learning (Vol. 21). Multilingual Matters. Veselá, Z. (2003) Czech Republic’s unrivalled system of marked walking trails. Radio Prague International, 5.12.2003.

0 Comments

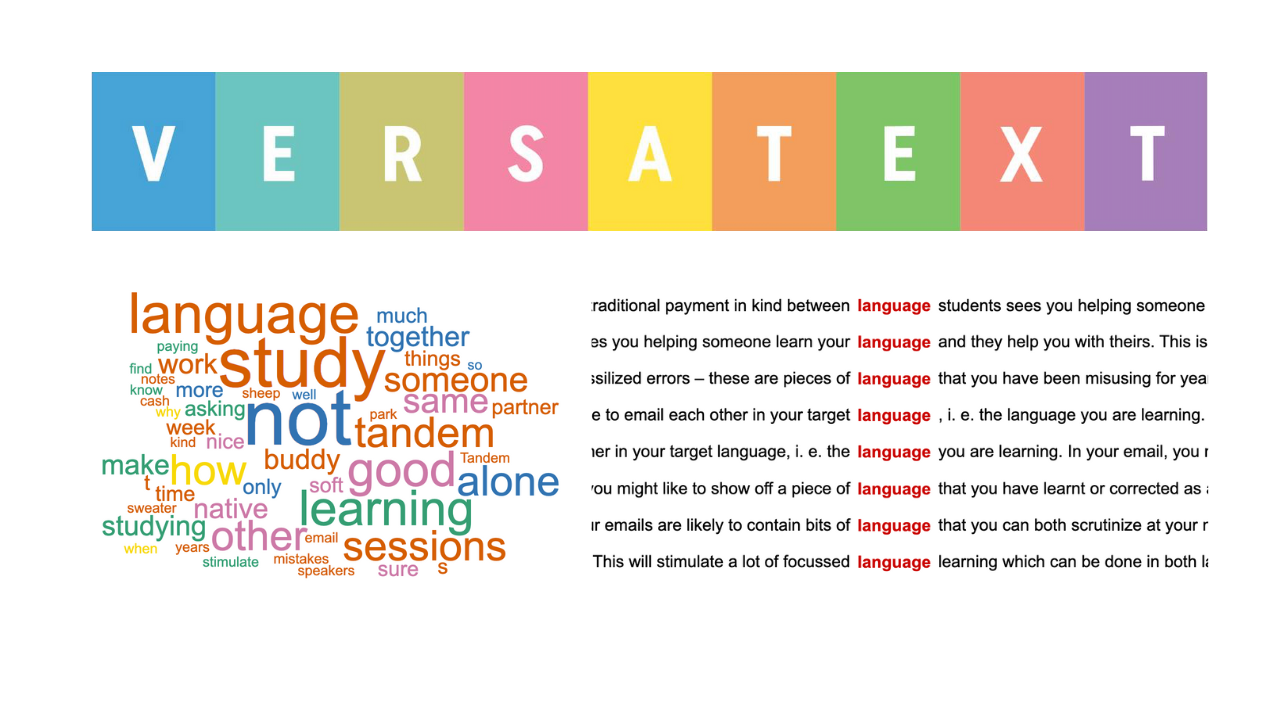

Collocation and VersaTextI had an email from a teacher who loves using my VersaText tool with his students. In addition to the very welcome and rarely received praise for VersaText, he was enquiring into the possibility of adding a collocation feature. As you know, VersaText works with single texts, its slogan being, “learning language from language, one text at a time”, collocations are vanishingly rare. In fact, “vanishingly rare” is a strong collocation in English. Check out the examples in #SkELL.

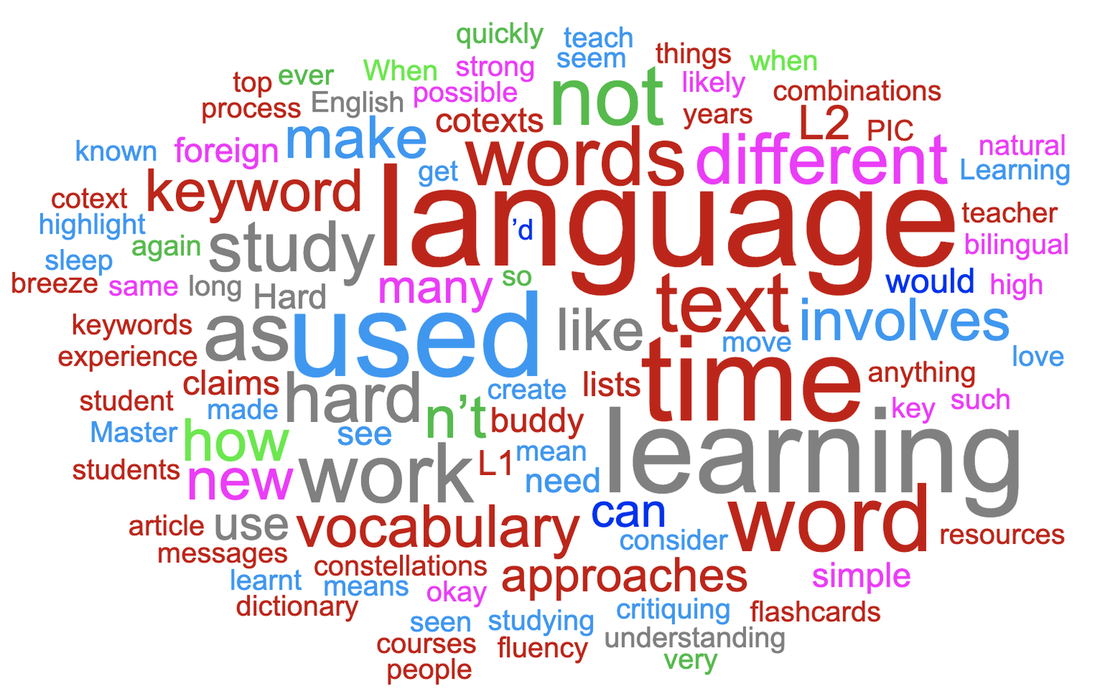

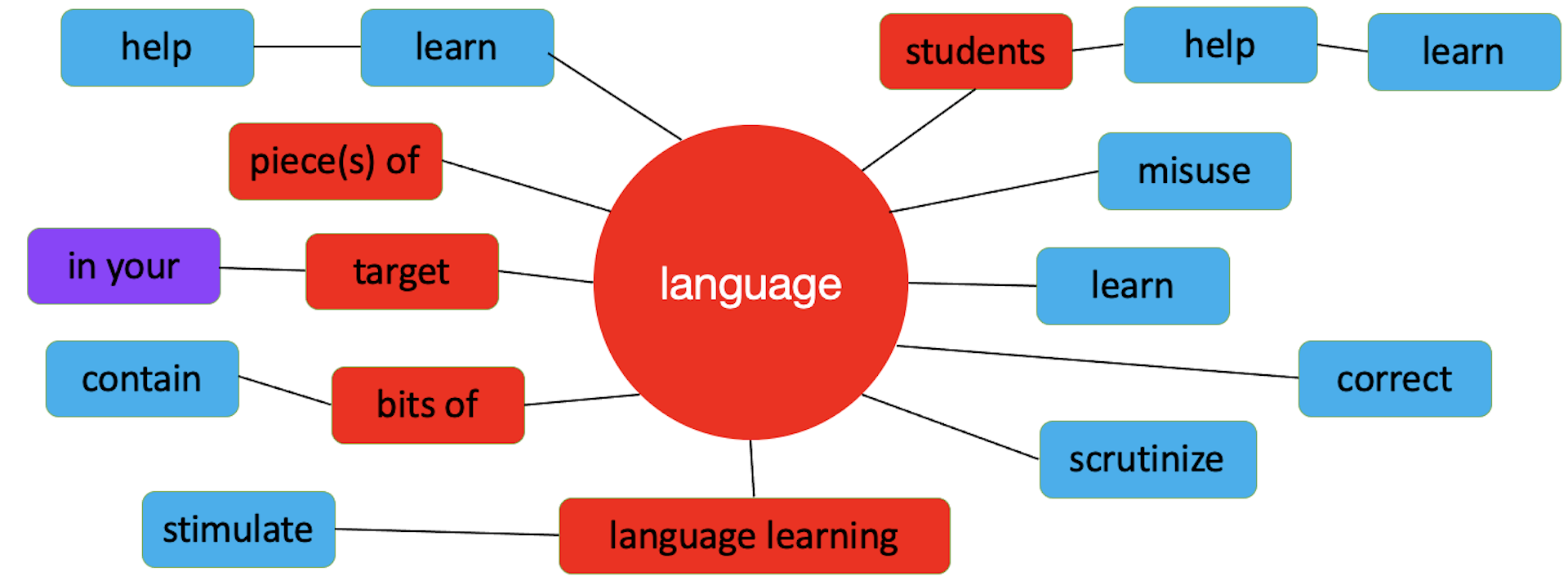

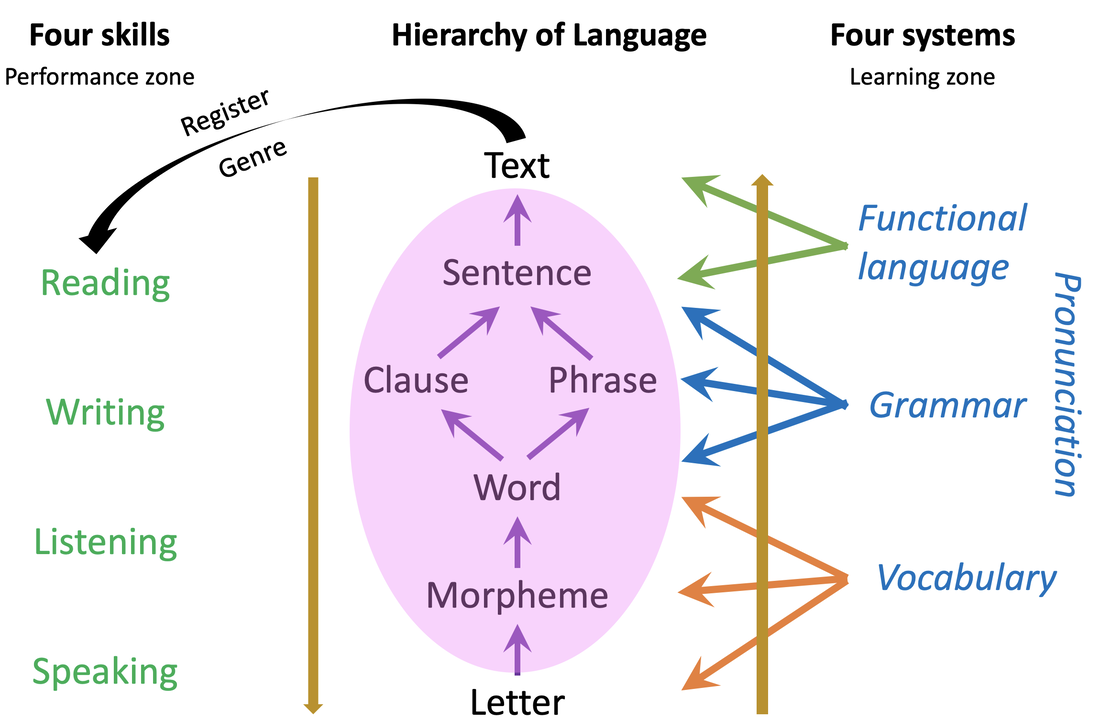

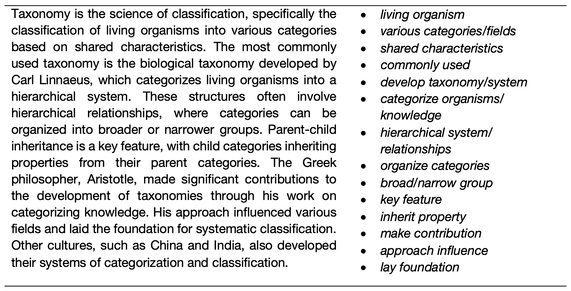

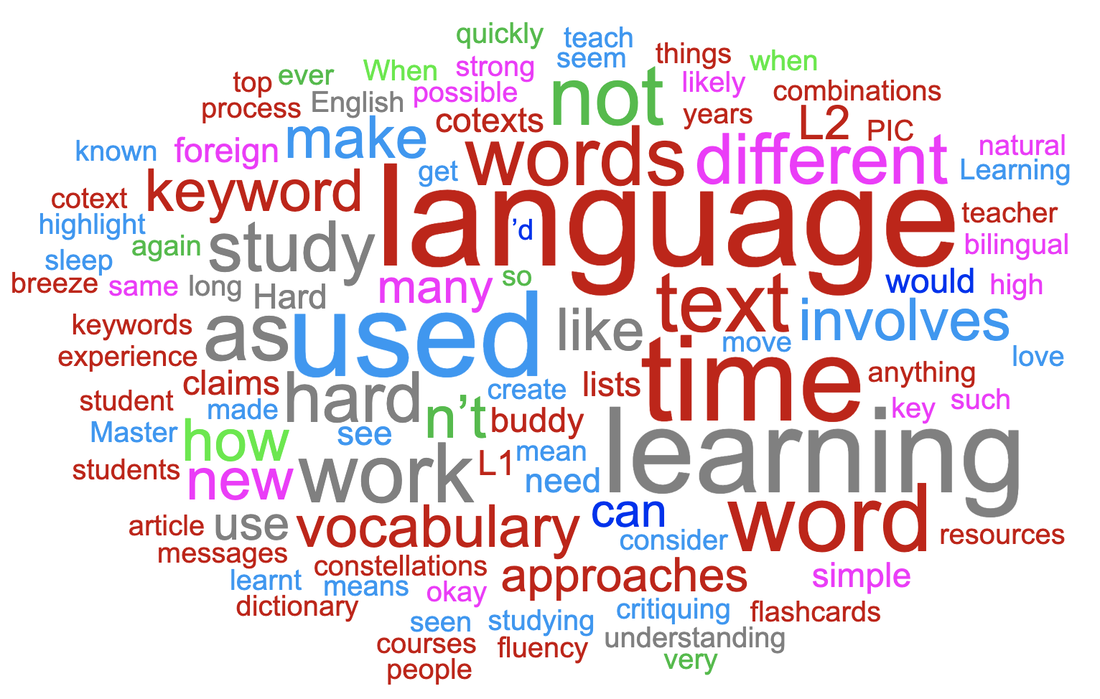

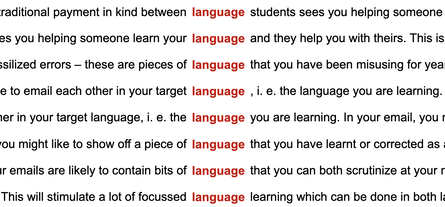

#Collocation is defined variously. First and foremost, collocation consists of two content words of different parts of speech. Compound nouns and adjectives, phrasal and delexical verbs are not collocations. And neither are words that combine with that/ -ing / inf / wh-/prepostions. These are colligations and offer very little choice, if any. You’ve all seen gap fills in coursebooks and exams that test this. Collocation does permit some variation, but within limits of acceptability if you are going to use the patterns of normal usage of the language. One category of definitions of collocation revolves around statistical frequency. These definitions rely on the number of times words occur in close proximity to each other. The verb collocates of trouble, for example, occur frequently within four words before and/or after the noun in SkELL's huge sample of English. Other definitions of collocation are phraseological: cause trouble is the core of a clause, which is the essential structure that creates Messages, which in turn constitutes text. Up the Hierarchy of Language we go! Most key words in most texts collocate with different items because the author is telling us something new about the word. And this is why a collocation tool in VersaText would be by and large redundant. One thing we can be sure of in a text is that the author is not going to repeat the same message repeatedly, again and again, over and over, unless they have some rhetorical reason for doing so. Here is an example. In VersaText’s sample text, Learning Zone (a transcript of a TED Talk), we see that the verb spend is frequently used with time, and with other time words, e.g. minutes, hours, our lives. It occurs 13 times in the text. Time occurs 28 times in the text and is used thus: CTRL F in the browser highlights the nominated word as it occurs in the cotext of the target word. Improve occurs 15 times in the text, each time in a different Message. This is far more typical of words in text than a frequently used collocation like spend time. Go to VersaText, select the Learning Zone text from the list, then click Wordcloud at the top. If you want the lemma of improve, for example, choose the lemma radio button under the word cloud. Click on any word to see its concordance in this text. This motivates many discovery learning tasks for the students. If you want to learn more about studying and teaching English with VersaText, click the Course button at the top of the VersaText pages. My phraseological approach to collocations in single texts is the Word Constellation. See my blog post linked below. This is a word constellation. It is built upon a VersaText concordance of the word language in text about language learning.

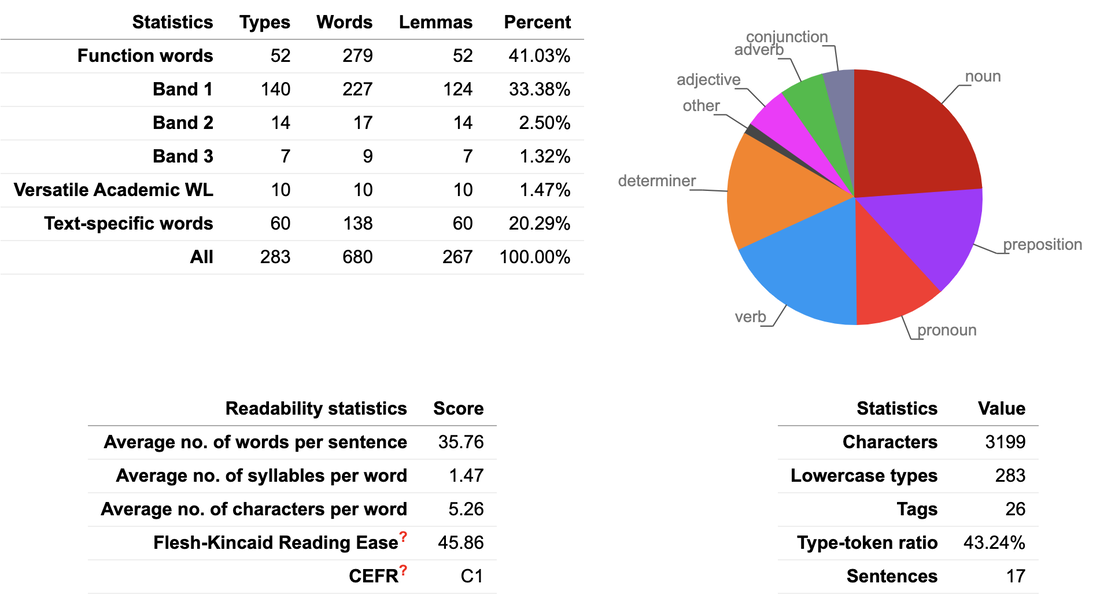

Learning language from language with VersaTextEvery layer of the hierarchy of language can be explored by students in a text. The exploration of Texts as Linguistic Objects (TALO) reveals how an author has used words and word forms, combined them as collocations and colligations, formed phrases and clauses that are linked with metadiscourse chunks to ultimately form texts. This is the bottom-up process that we employ both subconsciously and consciously when we speak and write. As well as being linguistic objects, Texts are also Vehicles of Information (TAVI) which invoke top-down processes as we combine the content of the text with what we know about the world through schemata, general knowledge and our expectations of text types. In this way, readers and listeners are engaged in their own personal knowledge creation. Thirdly, Texts are Springboards for Production (TASP). We respond to texts by combining several texts on the same topic, by critiquing aspects of the text, and by discussing the potential impact of this new knowledge, for example. To put texts under the microscope, VersaText is an open access, web-based resource that allows teachers and students to paste in a single text. The program provides several tools that foster discovery learning. The first tool is the word cloud, which depicts not only the relative frequencies of words in a text, but it colour-codes part of speech. The word cloud is highly customisable: the number of words, the choice of words vs. lemmas, which parts of speech to show. The relative sizes of words in the word cloud illustrate the extent of repetition in a text and repetition is the most commonly used resource to create lexical cohesion in text (Halliday & Hasan, 1976). When you click on a word in the word cloud, it shows a concordance of that word in the text. The concordance lines are in text order, which shows how the meaning of a key word evolves through different cotexts (Hoey, 1991). Inferring the meaning of an unknown word when it is shown in at least several cotexts is a far more realistic expectation than doing so from a single meeting with a word. It is possible to observe the use of articles with the first and subsequent noun references. Other colligation patterns can also be observed, such as the use of that and wh- clauses, and bound prepositions. Collocation, when defined as a frequency phenomenon, is not a pertinent feature of a single text, as a collocation is a unit of meaning that authors do not need to repeat. A phraseological definition of collocation is therefore more appropriate here (Partington, 1998). It is not uncommon for a text to include many verbs that collocate with a key noun. Observing collocation in such authentic contexts is an authentic learning task, as is employing said collocations in TASP. As students observe the key words in a text and their cotexts that create each of the author’s messages or propositions, they are not only engaged in TALO but they are also deepening their TAVI. Engaging such higher order thinking skills respects the intelligence of our students unlike so-called “tasks” such as multiple choice comprehension questions and gap filling. In addition to word clouds and concordances, VersaText provides text statistics including an estimate of a text’s CEFR level. It also shows the percentages of words that are function words, three bands of content words, academic words and text-specific words. It also lists all of these words in these categories in tables which can be used by teachers and students who are especially focused on vocabulary development. The opportunity to put the language of a single text under such a microscope is invaluable to students of CLIL, EMI and ESP, as the texts are models of the language of subjects and fields that the students need to have a productive knowledge of, if they are to be acculturated into their subject disciplines. This is essential for TASP. Feel free to join the VersaText Facebook Group where you can share your experiences and learn from others. ReferencesHalliday, M.A.K. & Hasan, R. (1976) Cohesion in English. Longman

Hoey, M. (1991) Patterns of Lexis in Text. OUP. Johns, T., Davies, F. (1983) Text as a vehicle for information: the classroom use of written texts in teaching reading in a foreign language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 1 (1) Partington, A. (1998) Patterns and Meanings: Using Corpora for English Language Research and Teaching. John Benjamins. Reach for the stars and draw a constellation. Happy new year!How often have you seen claims like these?

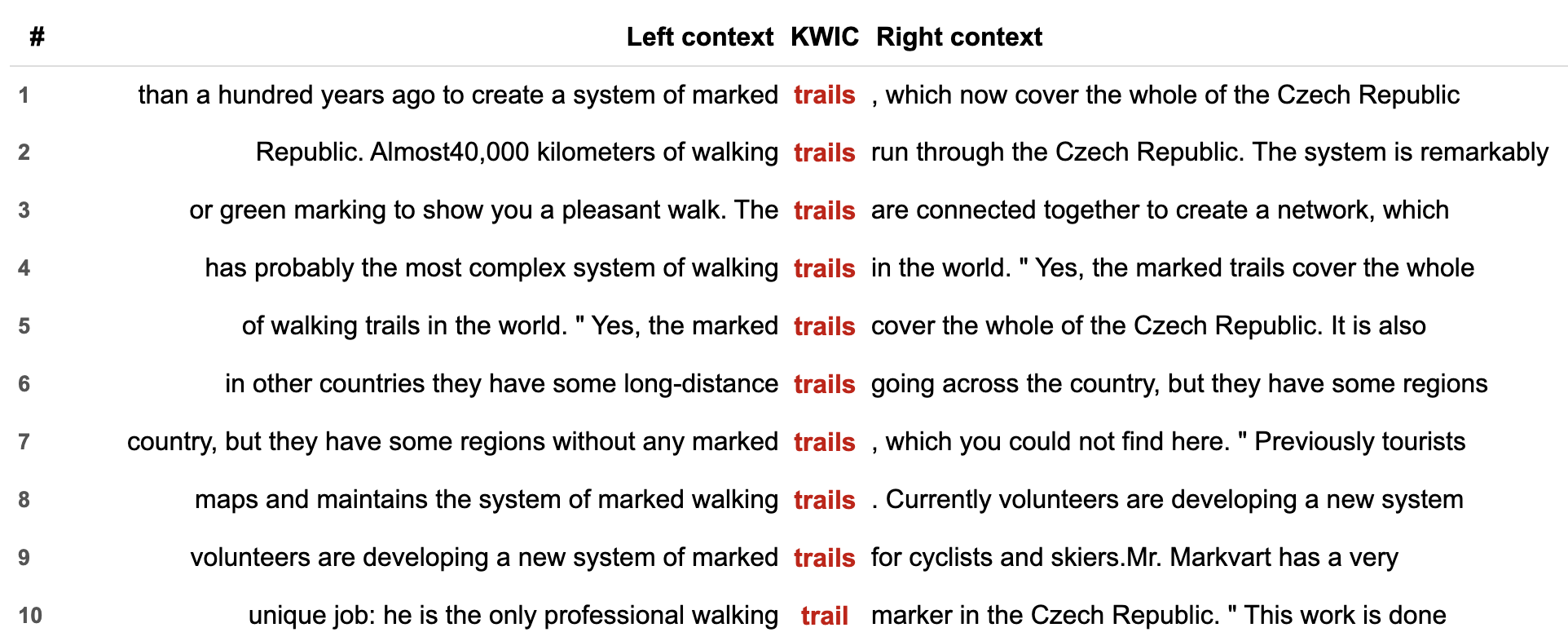

Who would make such claims? Certainly not someone who has achieved a high level of competence in a foreign language. As an eternal language student, and a language teacher and a teacher of teachers, I am pretty certain that you and I have worked hard to get to where we are in our foreign languages. It was not effortless, it wasn’t a breeze and no progress was made while we were asleep. I was so desperate to improve my vocabulary, that I used to sleep with my dictionary under my pillow. No I didn’t, but that is the impression you get from some of these slogans. Learning a language is hard work and there ain’t nothin’ wrong with hard work. Do not confuse hard work with hard labour. Hard doesn’t mean boring and monotonous and it doesn’t mean frustrating and unrewarding. 100 lemmas from this blog post, thank you VersaText. The hard work we do when learning a language involves planning, monitoring and revising. It involves understanding what we are learning, which in turn involves connecting what we already know with what is new to us. Hard work involves practising what we have learnt so that it becomes automatic. Hard work involves using our time efficiently, choosing approaches that work for us. This requires us to assess or critique the approaches to language study that are introduced to us if we are fortunate enough to have various approaches. It is worth reflecting on how many different things we are learning while studying – the learning affordances of an activity. For example, if we are learning a set of words with their first language equivalents, whether in written lists, on paper or electronic flashcards, in a computer game or being tested by our study buddy, the only connection we make is between the L1 and L2 word. We do not learn how the word is used. This leads us to assume that the L2 word is used in the same way as it used in L1 and this is okay when it works. It is not okay the rest of the time. This assumption is referred to by psycholinguists as the semantic equivalence hypothesis (Ijaz 1986, Ringbom 2007), Another issue with learning L1 - L2 pairs is the mental processing of the L2 word: what is your mind doing whilst trying to remember a word? Lower order thinking does not make for a rich learning experience. When we are critiquing our approaches to vocabulary study, we need to consider how many different things we are learning at the same time, a.ka. the affordances. When we study the vocabulary of a text in a text, we see how keywords are used differently each time it is used. Their different uses create different messages which means that the author is telling us something new about the keyword each time it is used. These different messages involve different words, which means we can make a diagram of a keyword as it is used in a text. I call these diagrams Word Constellations. Word constellation from the Czech Walking Trails article (Veselá) We can identify a key word and highlight all of its occurrences in the text, then highlight the words that are used with it. I prefer to do this with VersaText because it is easy to see the left and right cotexts of keywords in a concordance. You can do this with at least several key words in the text. Concordance of trails in said article created in VersaText In critiquing this approach, we need to consider how much was learnt during the time spent. Did the knowledge gained empower us to use the keyword and its cotextual words better than learning such combinations from flashcards or bilingual lists? Did we meet any combinations of words that were new and useful? Did we have to check our dictionary for anything? Did we notice anything about the distribution of the keyword through the text? Did the process heighten our understanding of the text? Did drawing the word constellations feel like a strong learning experience? Was it an enjoyable process? Can we imagine many of these in our vocabulary notebook? Are we likely to refer to them again? And again? Once we have a keyword in its multiple cotexts, we can use these as the bases of our own sentences. We might like to use them to form questions to discuss with our study buddy or our favourite AI tool. Here are some simple examples of a chat with Perplexity.ai. I'm a B1 student of English. Will you be my study buddy today? Of course! I'd be happy to help you with your English studies. Are Czech walking trails a complex system? Are they connected together? Do they run through the whole country? Is this time-consuming? Is it a good use of our time? Are we having strong learning experiences? Are connections forming in our minds that have a high chance of becoming permanent? I used bilingual lists for many years, long after I needed to. I think that if I were to start another foreign language, I would need them as a beginner. But applying what I have actually known for a long time, I would move as quickly as possible to studying words with their natural cotexts. It is possible that people who make claims like those at the top of this article teach vocabulary in cotext, but from the courses and resources that I have seen over the years, it does not seem very likely. If you or your students ever create word constellations, I’d love to see them. And I love to know what the process led to. References

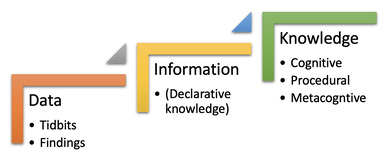

Ijaz, I. H. (1986). Linguistic and cognitive determinants of lexical acquisition in a second language. Language Learning, 36(4): 401-451 Ringbom, H. (2007). Cross-linguistic similarity in foreign language learning (Vol. 21). Multilingual Matters. Veselá, Z. (2003) Czech Republic’s unrivalled system of marked walking trails. Radio Prague International, 5.12.2003. Some years ago, I was part of an EU funded “experiment” in which a group of scientists worked with a group of English teachers to co-create a semester-long “science in English” course for non-native speaking university students. Non-native speakers of English, that is! Unfortunately, I was the only native speaker of English in the group and unfortunately, my expertise as an applied linguist, teacher trainer and materials writer were not in high demand. I was just the native speaking English teacher who could offer alternative wordings and arbitrate quandaries about the pronunciation of a word. Negotiations among the dozen people were mostly awkward as the approaches of science teachers were largely incompatible with mindset of the English teachers. The English level of the science teachers was quite low and therefore most of the planning meetings were not held in English. One of the most important things I learnt during this “science experiment” was that the fun-and-games communicative mindset of the English teachers did not challenge the science students “sciencly”. Science students learn about their world through identifying patterns and relationships in the data they explore, structuring their observations and combining their findings with the information they get from books, articles and lectures. They develop their cognitive, procedural and metacognitve knowledge in concert with their factual knowledge (a.k.a. information). Surely they could learn English in this way too. As just-the-native-speaker in the room, there was no opportunity to offer such a radical departure from the attempt to “funify” the high stakes, serious business of language learning. The alternative would have involved teaching the students how to learn language from the language they read, listen to and watch. They would use this input as data from which they would be guided to discover patterns and relationships in the language that they could ultimately use in their own speaking and writing. Another strand running through this course was soft skills training, which amounted to little more than reminding presenters to speak slowly and clearly, maintain eye contact and make sure you don’t have too many words on your slides. These wise words were typically shared in feedback. Improving the students’ use of English was not germane. A particularly telling moment was when one of the relatively young science teachers in the group pointed out that some of the English teachers in the group were his university English teachers not that long ago, and now he understands why his English level is so poor. He unwittingly agreed with Michael Swan’s bon mot: Language teaching is teaching language. Or is it: Engish teaching is teaching English? The whole experience strengthened my resolve to help students learn language from language in ways which are commensurate with their age, needs and sophistication. Their professional careers depend on a professional level of English, which for most learners does not emerge from extensive reading, role plays, soft skills and fun.

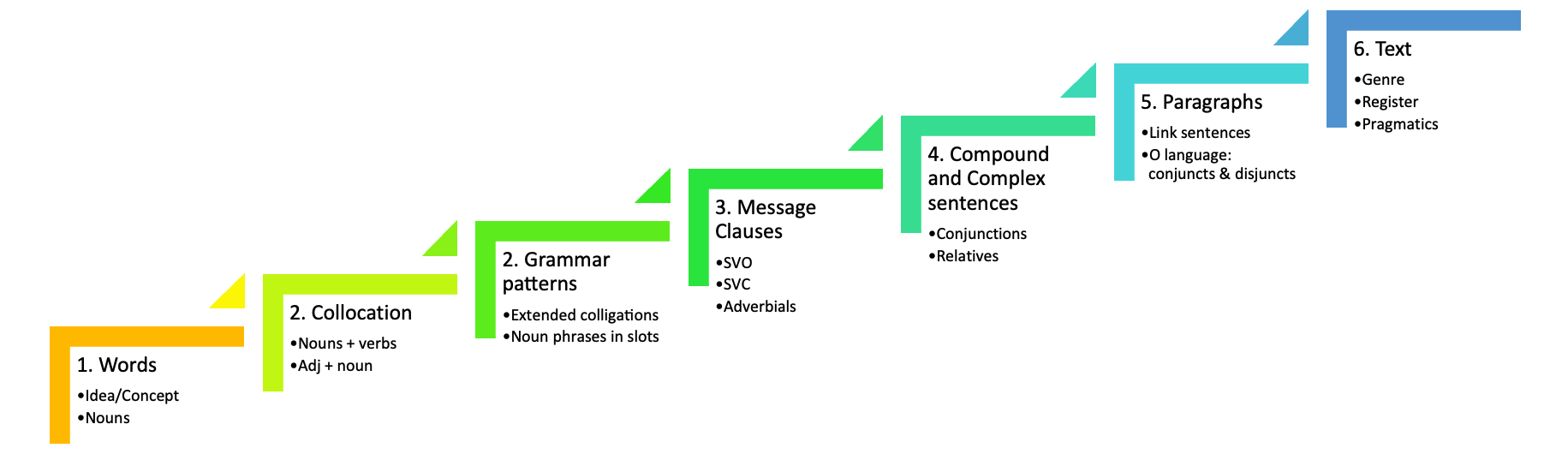

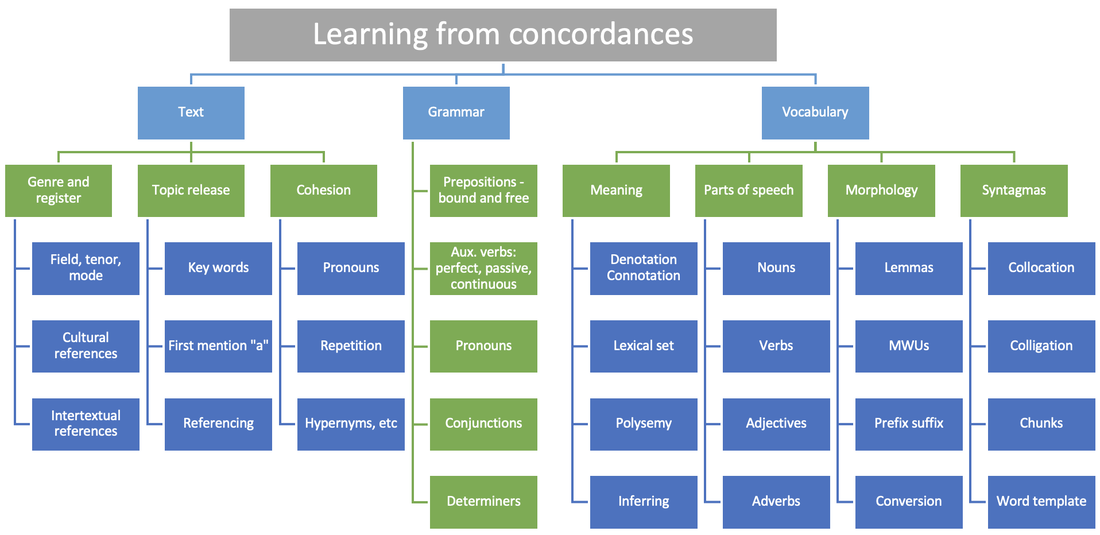

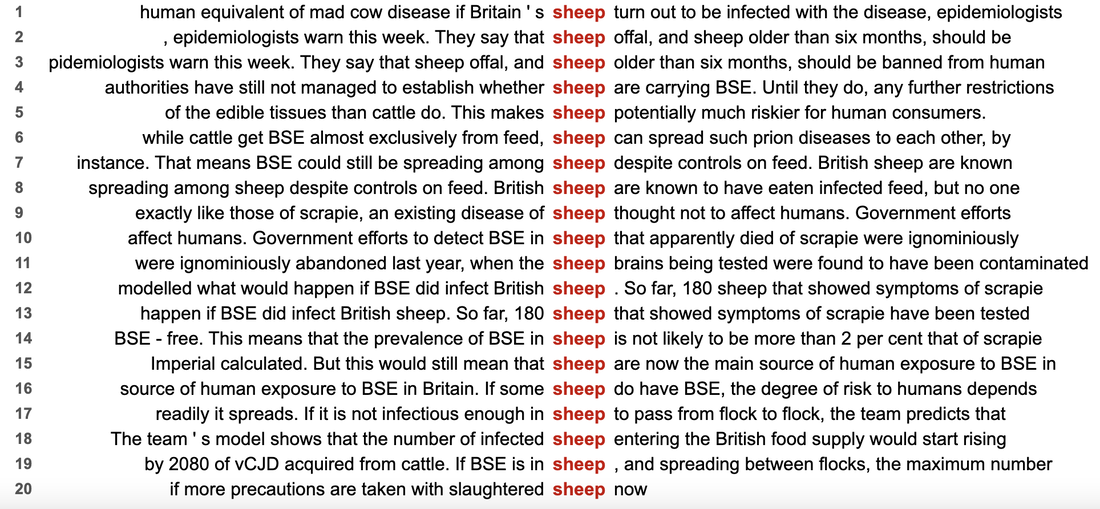

Yesterday, I read two current academic papers by esteemed colleagues. Is DDL dead? by Dr. Peter Crosthwaite and Prof. Alex Boulton. I co-edited a book of conference papers with Alex in 2012 and I presented my Discovering Academic English (2022) work in one of Pete's webinar series last year. The second paper, Generative AI and the end of DDL was written by the same Peter and Dr. Vit Baisa. I have been working with Vit for many years – he programs my VersaText and Pete's CorpusMate. The full titles of these works are in the references below. Data-driven learning (DDL) is an approach to studying language through treating language as data. Just as journalists, scientists and spies seek patterns in data so as to understand their subjects better and be able to make predictions, linguists including budding linguists, make and record their observations of features of language that they observe in authentic data. Being a discovery-based and inductive approach to language learning means that it is not suitable for every learning context, which is equally true of drilling, gap filling and using flashcards. DDL is one of many acronyms used in this article. They are listed at the end. Is DDL dead? reports very positive findings by researchers working in all corners of the globe over the last thirty years. Nevertheless, the authors identified a number of problems in the theoretical underpinnings of DDL, and with the actual corpus tools, and in the lack of cognitive studies, and even with the conduct of the research. They mention other drawbacks of DDL such as the technical knowledge required to use the tools, the fact that search tools work differently from other search engines, and that some corpus data is unsuitable for some learners. The second paper suggests that AI could potentially contribute to DDL but it is too soon to say. They argue that corpora still have a role to play in data-driven learning because corpus tools show where the data came from. Also, the data is authentic, unlike AI generated texts. The authors refer to them as hallucinations. They also point out that the inductive work done by students when working with corpora is actually done by ChatGPT, and not by the students. I have been immersed in DDL since the late 1990s, working with teachers and trainees and with students of academic writing. I have created e-learning courses, worksheets, books and have presented this work at conferences, some of which I have hosted and been on committees for. In the process, I have read many research papers and books on corpora and also on grammar, vocabulary and everything in between. So, I feel their pain. Many of the researchers cited in these two papers, and many more besides, regret that DDL has not become a standard modus operandi among internet savvy students and teachers in internet-wired homes and schools. The findings of these researchers has empirical credibility, but there are other issues that need to be addressed in order to alleviate the pain. And this is what I would like to focus on in this article and in several that will follow it. DDL focusses largely on the minutiae of language. The students are tasked with identifying patterns in the language by exploring the data. So far so good. But it is important that the students also learn how to record their findings, as they do in science experiments, for example. If they do not integrate their findings into previous schemata, much of the value of the task is lost. My Versatile Blank Book provides students with approaches to recording their findings systematically, intelligently, graphically and creatively. In addition, students need to apply their findings to their own language output. The students didn't discover the most frequent preposition that follows a particular adjective just to answer that guided discovery question. They discovered this to use the adjective confidently, to learn that different prepositions are used with different adjectives in patterned ways, and to learn how to observe such features of language. These affordances of DDL need to be articulated. The course books I have worked with over the years and seen at recent conference stands, and the resources which well-meaning teachers share in their Facebook and Pinterest groups, are not rich in opportunities for students to treat language as data or to exercise their intelligence and creativity. I remember my heart sinking when I once walked into Foyles bookshop on Charing Cross Road (London) to see "Celebrating 25 years of the world's best-selling grammar book", which many a reader of this post possibly also celebrated along with the author, Raymond Murphy. Such resources do not engage students in knowledge creation, rather they feed students a diet of matching activities and gap fills regardless of the age, level or motivation of the student. By the way, these are testing not teaching procedures. Grammar, vocabulary and everything in between are mostly poured into students' heads as information that can be presented and tested. This deprives students of the reality of language, namely the patterns and relationships that permeate everything we know about language. And we know a lot more about language than we did 50 years ago thanks largely to corpus studies. This diet of lower order thinking (LOTS) skills work deprives students of the opportunity to develop their knowledge about language (KAL) and the skill of learning language from language. It would be interesting to read the aims and objectives atop the lesson plans which DDL researchers have been studying. By the end of this lesson, the students will be able to … It would be equally interesting to read what the students write in their reflections on these lessons. From what I remember of the papers I read and edited quite some years ago, the research is mostly conducted under research conditions, not in classes led by teachers who are committed to this mode of language teaching and study. For the VersaText e-course I have just finished writing and which is currently being piloted by a few kind individuals, I created the taxonomy below. It will undergo some revision as it matures, but it nevertheless attempts to show what language students can learn from guided discovery tasks that require them to explore discrete aspects of language. It helps formulate aims and objectives, even though this linguistic minutiae is only a stepping stone to improved competence in the four skills. It also contributes to the development of their metacognitive competence. I suspect that any student or teacher of IELTS, TKT or DELTA could derive some benefit from this. Every feature of language begets a language learning task. For example, if we corpus aficionados want to study phrasal verbs and teach students how to study phrasal verbs, we need a clear definition of ‘phrasal verb’ and we need discovery tasks that can be solved through corpus consultation, and students need to be trained in reporting and applying their findings, just as any research scientist needs to do. One of the interesting things I have found in my EMI training is that university teachers of STEM and MBA subjects readily grasp how language can be treated as data and how patterns and relationships can be extrapolated. They just need to be told. In fact, one professor of horse surgery, upon his first introduction to corpus work, thanked me for making myself redundant (as a language teacher). He got it immediately. Many of our students major in STEM, MBA and medical subjects and do have the required mindset to learn language from language. Another issue besetting ELT is that KAL is not a high priority. No other subject so readily dismisses the theoretical foundation on which it is built (Marr and English, 2019). People place a lot of faith in osmosis, i.e., learners will acquire the language through vast exposure and by being required to do activities that will exercise what they know and force them to struggle to express ideas that they don't have the language for. Mind the gap! A considerable body of research supports my anecdotal experience that osmosis does not work for many people (Hinkel, 2006). For any learner who requires a professional level of a foreign language, attention to detail is essential. This may not be obvious to anyone who has never aspired to learn a foreign language to a high level. Language teaching seems to have leapfrogged language and is nowadays preoccupied with inclusion, empowerment, digital literacy, creativity, learner autonomy, gamification, global issues, critical thinking and soft skills (Kerr 2022). On a casual stroll through the list of topics that conferences cover, you will be unlikely to bump into many language topics. However, in order to pursue any of these worthy passions in a foreign language and with any degree of sophistication and nuance, the students need the principle resource for the job, namely a sophisticated and nuanced level of English. To facilitate this, double processing is recommended. This involves using the associated reading and listening for language as well as for content – explore the linguistic features of the key words and then use them in the writing and speaking tasks that follow. One of the reasons I created VersaText was to facilitate the study of the language of single texts. In this concordance of sheep from an article about BSE, we can see what the text is saying about the target word as well as how the author has said it. The aim is not to infer the meaning of sheep! I hope to finish in 2024 a B1 and a B2 activity books, both of which I would like to subtitle, More fun than Murphy, but better not. These books teach students language, about language and about language learning, using tools such as SkELL, VersaText and CorpusMate. The students will be doing “task-based linguistics” from the first to the last pages. AI was not integrated into these books when they were being drafted, but it would be profligate to ignore the opportunity that this new technology affords. If you would be interested in piloting these books with your students, please message me. I will say more about the pitfalls and potential of DDL in follow up posts. Thanks for reading and I look forward to your comments. AbbreviationsDDL: data-driven learning coined by Tim Johns (1990) AI: artificial intelligence LOTS: lower order thinking skills (cf. HOTS) IELTS: International English language testing system TKT: teachers knowledge test (a Cambridge exam) DELTA: diploma in English language teaching to adults EMI: English as a medium of instruction (university teachers teach their subject in English) STEM: science, technology, engineering, mathematics – a class of school subjects MBA: masters in business administration ELT: English language teaching KAL: knowledge about language BSE: Bovine spongiform encephalopathy a.k.a. mad cows disease a.k.a.: also known as ReferencesCrosthwaite, P. & Boulton, A. (2022). DDL is dead? Long live DDL! Expanding the boundaries of data-driven learning. In H. Tyne, M. Bilger, L. Buscail, M. Leray, N. Curry & C. Pérez-Sabater (Dir.), Discovering language: Learning and affordance. Peter Lang.

Crosthwaite, P. & Baisa, V. (2023) Generative AI and the end of corpus-assisted data-driven learning? Not so fast! Applied Corpus Linguistics. Vol. 3 Issue 3. Hinkel, E. (2006) Current Perspectives on Teaching the Four Skills. TESOL QUARTERLY Vol. 40, No. 1. Kerr, P. (2022) 30 Trends in ELT. CUP. Marr, T, and English, F. (2019) Rethinking TESOL in diverse global settings: The language and the Teacher in a Time of Change. Bloomsbury Academic. Thomas, J, & Boulton, A. (2012) Input, Process and Product: Developments in Teaching and Language Corpora. Masaryk University Press. Thomas, J. (forthcoming) Discovering Academic English. Thomas, J. (2022) Versatile Blank Book. Versatile Publisher. November 17th is a public holiday in Czechia, the Struggle for Freedom Day. It marks the protests held on this day in 1989 which led to the Velvet Revolution. Fifty years earlier on this day, Czechs had protested the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. Many shops and offices celebrate the day by working, business as usual. November 17th is also the birthdays of two friends: Jeff who set up my Versatile Moodle site about 10 years ago and Pavel who plays bassoon in the opera orchestra. Brno opera is performing Peter Grimes tonight, the first of three reprises of this stunning production which I didn’t see when it premiered a few years ago because I was working in Tashkent. I bought six tickets for my firends, so we’re in for a superb evening. Brno's production of Peter Grimes Despite being a public holiday and the birthdays of friends and an opera to look forward to with other friends, the best thing about today was the first post I read this morning. One of my Tashkent students, Muborak Hazratkulova, was so taken with SkELL and VersaText, that I always introduce in my teacher training and my books, that she submitted a proposal to present her work with these tools at TESOL in Oregon, which was accepted but she was unable to secure funding for the trip. Since then she has presented this work at two conferences. Lubos and me in Samarkand. He was the only Czech friend who visited me there. COVID lockdown started during his visit and he had the devil's own job getting evacuated a week later. The first was in Samarkand and she was then selected to present it again at Inha in Tashkent by the American Councils. Her message this morning began, Dear Professor, I am writing to express my heartfelt gratitude … It concludes with thanks for helping her increase her knowledge about integrating technology in the classroom which she now shares with other teachers. At the moment, several people are piloting a new e-course I spent a month creating recently. It teaches teachers how to use VersaText when creating text-based lessons and I plan to launch it early in the new year. I will now reply to this ex-student, conference presenter and promoter of SkELL and VersaText, and invite her to be a pilot.

PS While uploading photos for this post, bassoonist Pavel has just texted me to say that the opera tonight is cancelled because the Swedish singer in the title role has COVID. I’ve spent too much of the last forty years of my life learning foreign language vocabulary, as well as quite a lot of new words and concepts in my native English but this was through different means for different ends. Most of my early foreign language vocabulary study involved learning from bilingual lists or flashcards, labelling pictures, matching foreign words with pictures or English words, and filling in gaps in strings of unrelated sentences. Having no reason to believe that my teachers or course books had set out to hinder my progress or waste my time, I kept plodding along at first in Italian, then German and later Czech. And some Russian.

By the time I started studying Czech, I had also become an ELT teacher around the golden eras of the COBUILD project and the Lexical Approach. Corpora were also peeking their heads above the parapet (data driven learning). This was the early 1990s and it promised great things for a more sophisticated approach to vocabulary study, one in which we would study and teach the properties of words, their internal and external relationships with other words, their roles in creating meaning. It was a time when “learning to learn” and discovery learning were establishing themselves in ELT. Empowerment through linguistic competence was in the air. It took me some time to absorb and apply these new trends to my self-study of Czech, but I’m glad I did. It was more difficult to squeeze into my English teaching as we had to turn the pages of course books in lockstep with external syllabuses. A few weeks ago I was at IATELF Poland, where I picked up a sample course book, fresh off the press from one of the Big 4 publishers. Having been a teacher trainer for 25 years, it came as little surprise that the approach to studying and teaching vocabulary espoused in this brand new course book has no made no headway since the Headways I was teaching from 30 years ago. In my teacher training, I always offer teachers vocabulary teaching activities that engage higher order thinking skills, creativity, discovery learning, metacognitive strategies, the double processing of texts and negotiating meaning. Many of the activities derive from contemporary findings in linguistics, such as grammar patterns as properties of words, and the role of collocation in creating meaning. In the books I have published in the last ten years, I have also provided teachers with lesson plans, activities and resources that elevate the status of vocabulary to its rightful place, that prevent teachers from hindering students’ vocabulary development and that provide students with rewarding self-study procedures. Teachers want their students to be more fluent, accurate, sophisticated and idiomatic (FASI) and a solid grasp of vocabulary is an essential ingredient. |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|