The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

|

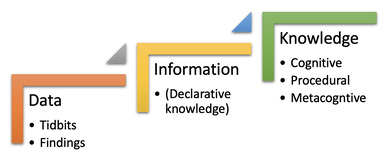

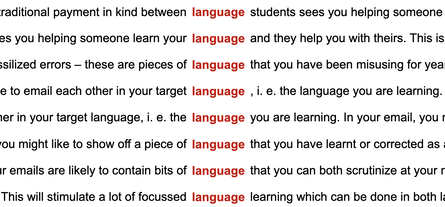

Some years ago, I was part of an EU funded “experiment” in which a group of scientists worked with a group of English teachers to co-create a semester-long “science in English” course for non-native speaking university students. Non-native speakers of English, that is! Unfortunately, I was the only native speaker of English in the group and unfortunately, my expertise as an applied linguist, teacher trainer and materials writer were not in high demand. I was just the native speaking English teacher who could offer alternative wordings and arbitrate quandaries about the pronunciation of a word. Negotiations among the dozen people were mostly awkward as the approaches of science teachers were largely incompatible with mindset of the English teachers. The English level of the science teachers was quite low and therefore most of the planning meetings were not held in English. One of the most important things I learnt during this “science experiment” was that the fun-and-games communicative mindset of the English teachers did not challenge the science students “sciencly”. Science students learn about their world through identifying patterns and relationships in the data they explore, structuring their observations and combining their findings with the information they get from books, articles and lectures. They develop their cognitive, procedural and metacognitve knowledge in concert with their factual knowledge (a.k.a. information). Surely they could learn English in this way too. As just-the-native-speaker in the room, there was no opportunity to offer such a radical departure from the attempt to “funify” the high stakes, serious business of language learning. The alternative would have involved teaching the students how to learn language from the language they read, listen to and watch. They would use this input as data from which they would be guided to discover patterns and relationships in the language that they could ultimately use in their own speaking and writing. Another strand running through this course was soft skills training, which amounted to little more than reminding presenters to speak slowly and clearly, maintain eye contact and make sure you don’t have too many words on your slides. These wise words were typically shared in feedback. Improving the students’ use of English was not germane. A particularly telling moment was when one of the relatively young science teachers in the group pointed out that some of the English teachers in the group were his university English teachers not that long ago, and now he understands why his English level is so poor. He unwittingly agreed with Michael Swan’s bon mot: Language teaching is teaching language. Or is it: Engish teaching is teaching English? The whole experience strengthened my resolve to help students learn language from language in ways which are commensurate with their age, needs and sophistication. Their professional careers depend on a professional level of English, which for most learners does not emerge from extensive reading, role plays, soft skills and fun.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|