The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

|

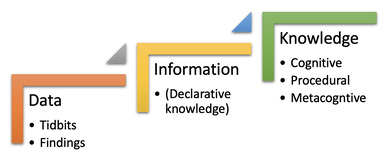

Some years ago, I was part of an EU funded “experiment” in which a group of scientists worked with a group of English teachers to co-create a semester-long “science in English” course for non-native speaking university students. Non-native speakers of English, that is! Unfortunately, I was the only native speaker of English in the group and unfortunately, my expertise as an applied linguist, teacher trainer and materials writer were not in high demand. I was just the native speaking English teacher who could offer alternative wordings and arbitrate quandaries about the pronunciation of a word. Negotiations among the dozen people were mostly awkward as the approaches of science teachers were largely incompatible with mindset of the English teachers. The English level of the science teachers was quite low and therefore most of the planning meetings were not held in English. One of the most important things I learnt during this “science experiment” was that the fun-and-games communicative mindset of the English teachers did not challenge the science students “sciencly”. Science students learn about their world through identifying patterns and relationships in the data they explore, structuring their observations and combining their findings with the information they get from books, articles and lectures. They develop their cognitive, procedural and metacognitve knowledge in concert with their factual knowledge (a.k.a. information). Surely they could learn English in this way too. As just-the-native-speaker in the room, there was no opportunity to offer such a radical departure from the attempt to “funify” the high stakes, serious business of language learning. The alternative would have involved teaching the students how to learn language from the language they read, listen to and watch. They would use this input as data from which they would be guided to discover patterns and relationships in the language that they could ultimately use in their own speaking and writing. Another strand running through this course was soft skills training, which amounted to little more than reminding presenters to speak slowly and clearly, maintain eye contact and make sure you don’t have too many words on your slides. These wise words were typically shared in feedback. Improving the students’ use of English was not germane. A particularly telling moment was when one of the relatively young science teachers in the group pointed out that some of the English teachers in the group were his university English teachers not that long ago, and now he understands why his English level is so poor. He unwittingly agreed with Michael Swan’s bon mot: Language teaching is teaching language. Or is it: Engish teaching is teaching English? The whole experience strengthened my resolve to help students learn language from language in ways which are commensurate with their age, needs and sophistication. Their professional careers depend on a professional level of English, which for most learners does not emerge from extensive reading, role plays, soft skills and fun.

0 Comments

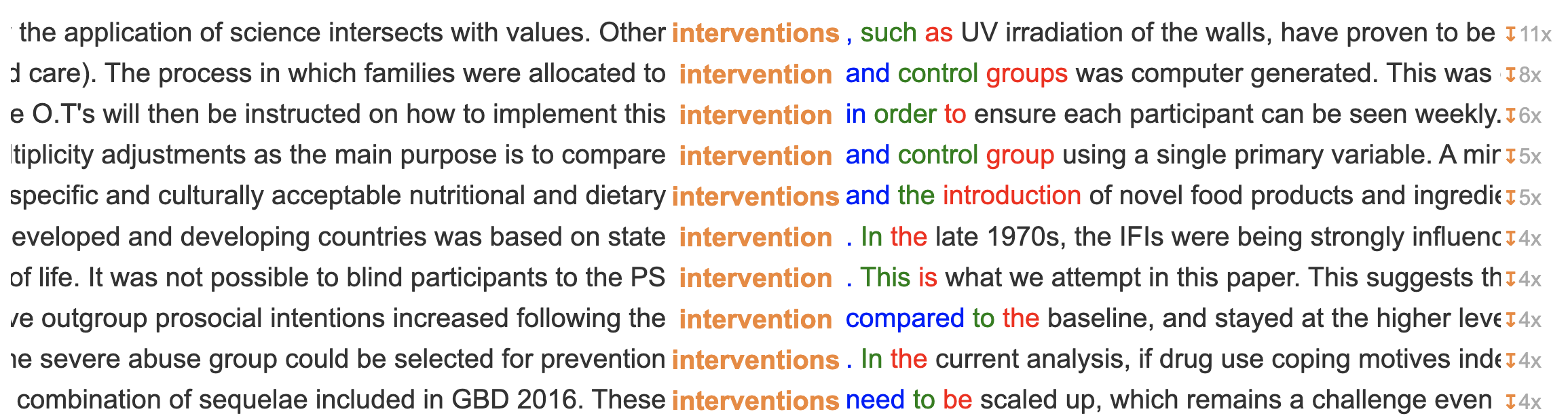

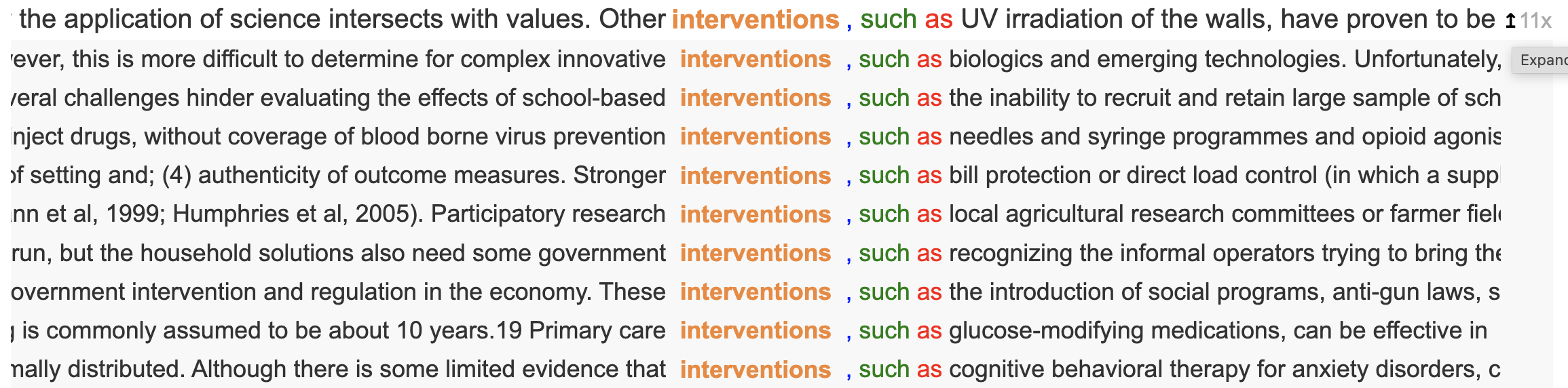

CorpusMate is the latest free, open-access corpus tool available on the web. It hails from the University of Queensland, which was recently recognised as the leading university in Australia. It was designed by Dr. Peter Crosthwaite and programmed by Dr. Vít Baisa. I should say here and now that Vít is also the programmer of SkELL and my VersaText, and I had lunch with Pete on his campus in June as we had only met online up to that point. Its clear and simple interface allows you to search for a word or phrase in its 50 million word corpus. You can focus your search in one of 20 topics such as biology, law, education and journalism. And you can also limit your search to spoken or written language. While it does not have a collocation tool, it does have a patterns tool: the search result is sorted according to the frequencies of patterns. The numbers on the right indicate how many instances there are. Clicking on the little arrows on the right shows the patterns. These are the 11 instances of the first pattern. This one happens to show hyponyms of intervention. The single page About page provides some background to the corpus, the sources of data, and most importantly, help on performing queries.

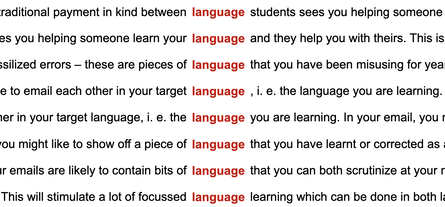

Last year I wrote a workbook, Discovering Academic English, that was used by about 500 students in an MA TESOL program. They learnt a lot of academic language and a lot about learning language through COCA (Corpus of Contemporary American English), but COCA was a steep learning curve for them and no matter how detailed the instructions were or how focussed the tasks were, many of the students found COCA difficult. They were frustrated by the limited number of daily searches and by frequently being taken to an invitation to pay. This was not the experience I wanted them to have. In the workbook I am writing now, the students will work with CorpusMate instead of COCA. CorpusMate has a much smaller corpus and fewer tools, which make it easier to use and easier to find results. I am hoping that students will warm to corpus use through the new guided discovery tasks. The searches are easy to perform and the results are clearly displayed. The aim is to promote their learning of academic English and their academic English! It is obvious when you put it like that. To ask if there are more meanings than words begs several more questions. We could start with: what is a word and what is meaning? Then we could ask how the numbers of these things are counted. We might even wonder who wants to know. Or as my grandmother used to provoke: how will knowing this change my life? Let’s start by appeasing my long-passed grandmother. To be honest, I am not sure that being aware of the fact that there are more meanings than words in a language (spoiler alert) would have changed her life as she was not a linguist in any sense of the word: she didn’t study languages and she didn’t study language. Bingo! Right there in that very statement the question manifests. Are the countable and uncountable forms of language one word or two? An orthographic word is a string of letters that has a space before and after it. This applies to the written word, obviously. Spaces in the spoken language do not separate words. When software counts words, this is the definition of word that it uses. But no one would argue that a text that contained a thousand words expressed a thousand units of meaning. No one is two othographic words but one lexeme. Lexeme is the term for a unit of meaning and while most meanings are expressed by orthographic words, very many are expressed by compound nouns, compound adjectives, compound prepositions, phrasal verbs, idioms, fixed phrases and chunks of various kinds. The day before yesterday is one lexeme made up of four orthogrpahic words. Made up of is a phrasal verb consisting of three words expressing one meaning in this context. The words that compose these multi-word lexemes are used in many others. Is there a difference in meaning between participate and take part in? In many languages, the day before yesterday is one word. A linguist in the old-fashioned sense meaning polyglot and the modern sense of language researcher have their own words in other languages. German has Sprachkundige for polyglot and Sprachforscher for the academician. Even without any knowledge of German, the interested reader will notice that the first syllable of these two words is the same and will therefore conclude that these are compound nouns without a space between the orthographic words that they consist of. Spaces and hyphens also confound the definition of word: in English, we write hobby horse, hobby-horse and hobbyhorse. This word also has very different literal and figurative meanings. Every dictionary has a different number of meanings for make. Some dictionaries lump together similar meanings and uses, while others split them into separate sub-entries. Lexicographers thus accuse each other of being lumpers and splitters. In fact, they are not alone. Lumping and splitting occurs in many fields wherever things are being categorised. But I digress. In delexical verbs, make doesn’t mean much at all: make a decision, make a comment, make a plan, make a promise, make a suggestion. In fact, in these cases, there are single word verbs that have the same meaning even though they are syntactically different. Compare: someone makes a plan and someone plans something. Delexical verbs are quite different from phrasal verbs as the latter contains only a verb + particle (prepositions and adverbs) and the meaning of many phrasal verbs results from the interaction of the verb with the functions of the particles. For example, one of the functions of up in phrasal verbs expresses completion e.g., clean up, wrap up. Another function expresses change, e.g. grow up, break up. Make up is two orthographic words and one lexeme. But the Collins COBUILD lists eight meanings of make up. These meanings result from the different functions of up. The Collins lists three meanings of the hyphenated noun form make-up. In the iconic expression of the 1960s peace movement, Make love not war, the denotation of make love is have sex. But the connotation carries more intimacy than the physical act. The 1960s protest movement was advocating warmth, harmony and love between people, not a biblical “go forth and multiply”. I often wonder why the hippies didn’t perform more music by Bach, after all he had 20 children with his two wives. Making war is something that politicians ultimately do. The military doesn’t make war. The military goes to war, wages war, fights battles. Anyone chanting Make love not war must have been directing the slogan at politicians. They wanted them to promote harmony between people instead of sending them to war.

On a lighter note, in an old pun on the word make, one guy says, My mother made me a homosexual (make = cause) and his friend replies, Would she make me one too (make = create)? Many words form phrases and idioms, and express jokes, puns and cultural references. Some words have shades of meanings that cause lumpers and splitters sleepless nights. Not every word is as polysemous as make, but many of the high frequency words in the language do have multiple meanings. Many of them also undergo conversion, that is, they function in more than one part of speech. How many parts of the body are both nouns and verbs, for example? And don't think that parts of the body and body parts are synonymous. Speaking of verbs that parts of the body do, consider the similarities and differences between these troponyms of 'go on foot': amble, stroll, wander, meander, saunter. And these troponyms of 'eat': nibble, devour, swallow, feed, consume. These words are not synonyms either. To borrow an analogy from database design, words and meanings have a "many-to-many" relationship. This is the type of relationship between two entities where each element of one entity can be associated with many elements of another entity, and vice versa. Many words, though not all, have many meanings, and many meanings are expressed by orthographic words and by multi-word lexemes. This knowledge about language (KAL) would not have been of much use to my grandmother but for the billions of people who are both Sprachkundige and Sprachforscher in the modern world, being equipped with concepts about vocabulary enables them to systematise their study. It makes learning visible. It is not necessary to second-guess things. Knowledge is power. |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|