The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

Reach for the stars and draw a constellation.How often have you seen claims like these?

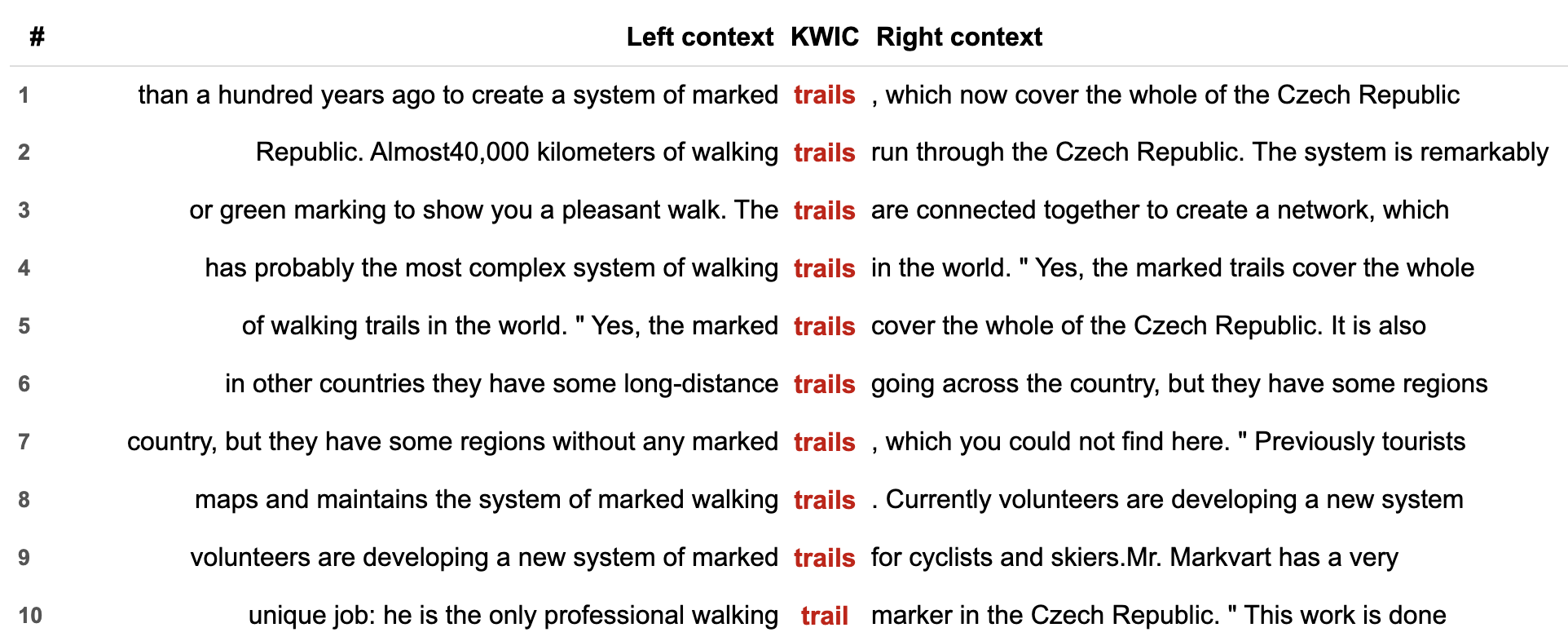

Who would make such claims? Certainly not someone who has achieved a high level of competence in a foreign language. As an eternal language student, and a language teacher and a teacher of teachers, I am pretty certain that you and I have worked hard to get to where we are in our foreign languages. It was not effortless, it wasn’t a breeze and no progress was made while we were asleep. I was so desperate to improve my vocabulary, that I used to sleep with my dictionary under my pillow. No I didn’t, but that is the impression you get from some of these slogans. Learning a language is hard work and there ain’t nothin’ wrong with hard work. Never confuse hard work with hard labour. Hard doesn’t mean boring and monotonous and it doesn’t mean frustrating and unrewarding. The hard work we do when learning a language involves planning, monitoring and revising. It involves understanding what we are learning, which in turn involves connecting what we already know with what is new to us. Hard work involves practising what we have learnt so that it becomes automatic. Hard work involves using our time efficiently, choosing approaches that work for us. This requires us to assess or critique the approaches to language study that are introduced to us if we are fortunate enough to have various approaches. It is worth reflecting on how many different learning experiences we are having while studying – the learning #affordances of an activity. For example, if we are learning a set of English words with their first language equivalents, whether in written lists, on paper or electronic flashcards, in a computer game or being tested by our study buddy, the only connection we make is between the L1 and L2 word. We do not learn how the word is used. This leads us to assume that the L2 word is used in the same way as it used in L1 and this is okay when it works. It is not okay the rest of the time. Psycholinguists refer to this assumption as the semantic equivalence hypothesis (Ijaz 1986, Ringbom 2007). Another issue with learning L1–L2 pairs is the mental processing of the L2 word: what is your mind doing whilst trying to remember a word? Lower order thinking does not make for a rich learning experience. When we are critiquing our approaches to vocabulary study, we need to consider how many different features of words we are learning at the same time. However, when we study the vocabulary of a text in a text, we see how keywords are used differently each time they are used. Yes, their different uses create different messages which means that the author is telling us something new about the keyword each time it is used. These different messages involve different words, which means we can make a diagram of a keyword as it is used in a text. I call these diagrams Word Constellations. We can identify a key word and highlight all of its occurrences in the text, then highlight the words that are used with it. I prefer to do this with #VersaText because it is easy to see the left and right cotexts of keywords in a concordance. You can do this with at least several key words in the text. In critiquing this approach, we need to consider how much the students learnt during the time spent.

If they didn't create a word constellation of a key word in a text, what did they do? How did they spend their time? What learning took place? Once we have a keyword in its multiple cotexts, we can use them as the bases of our own sentences. We might like to use them to form questions to discuss with our study buddy or our favourite AI tool. Here are some simple examples of a chat with Perplexity.ai. Hi. I'm a B1 student of English. Will you be my study buddy today? Of course! I'd be happy to help you with your English studies.

Is this time-consuming? Is it a good use of our time? Are we having strong learning experiences? Are connections forming in our minds that have a high chance of becoming permanent? I used bilingual lists for many years, long after I needed to. I think that if I were to start another foreign language, I would need them as a beginner. But applying what I have actually known for a long time, I would move as quickly as possible to studying words with their natural cotexts. It may be the case that people who make claims like those at the top of this article do actually teach vocabulary in cotext, but from the courses and resources that I have seen over the years, this does not seem very likely. If you or your students ever create word constellations, I’d love to see them. And I would love to know what the process led to. Feel free to join the VersaText Facebook Group where you can share your experiences and learn from others. ReferencesIjaz, I. H. (1986). Linguistic and cognitive determinants of lexical acquisition in a second language. Language Learning, 36(4): 401-451

Ringbom, H. (2007). Cross-linguistic similarity in foreign language learning (Vol. 21). Multilingual Matters. Veselá, Z. (2003) Czech Republic’s unrivalled system of marked walking trails. Radio Prague International, 5.12.2003.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|