The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

Snowclones adriftIt is a truth universally acknowledged, that a university student in possession of a strong academic vocabulary will be well on the way to toughing out their studies, for we know that when the going gets tough, the tough rush headlong into their studies and boldly go where no student has gone before. And other such exploitations of well-known expressions. You can see more examples of them in the SkELL corpus. And when you do explore them in SkELL, you can read the full sentences and make a wide range of observations. You can discover their original forms and observe how various people have exploited them. And talked about them. Remember that corpora generally consist of thousands of texts created by different individuals and a search provides a sample of the target word or structure. Because SkELL’s corpus is drawn from the internet, you can copy a sentence and Google it to see it in its source text and consider the author’s motivation for using it. You can consider the genre and register of the text: it is unlikely that they would be used in academic papers or in formal conversations. As you have probably heard, Eskimos have 17 words for snow, far more than any other language. This claim is as fatuous as the Great Wall of China being the only man-made object visible from space. And both of these statements are also snowclones, the term used for these linguistic exploitations. I have it on good authority (Wikipedia) that the term was coined by Glen Whitman, economics professor, in 2004, and the linguist, Geoffrey Pullum, endorsed it. Whitman’s inspiration for the term was the fatuous Eskimoan snow claim. Here are a few more snowclones that I have collected over the years. They have various origins and standard uses in English, but all are variously exploited as snowclones.

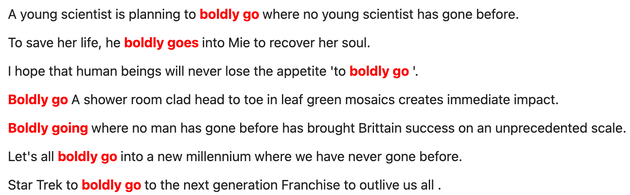

Like all linguistic phenomena, snowclones have been in existence much longer than the term coined to describe them. A term endows a phenomenon not only with a certain gravitas but a recognition that it has a set of features that an entity needs to be worthy of the name. If it has all of the required features it is a prototype (Rosch). Eleanor Rosch Most things deviate to some extent from prototypes, but if they have enough of the features in an adequate proportion, they can be thus labelled. The beloved example of semanticists is birds: which features of pigeons, eagles, emus, penguins and pterodactyls do they possess to be categorised as birds? Another fine example is the English language: which features of English do spoken Texan, Irish football journalese, and academic written English all possess? This makes for an interesting Venn diagram and it leads to a description of “core” English. A nice activity, by the way! Terms are of much use to language students and misuse impedes their progress. We are all familiar with the misnomers, past tense and past participle. As Michael Lewis convincingly conveyed, the past tense is actually about remoteness – in time, in reality, and in social distance. The past participle is a non-finite form and by definition cannot express time. Compound nouns and phrasal verbs are not collocations, and delexical verb structures are neither collocations nor phrasal verbs. Restaurant, bistro and canteen are co-hyponyms, not synonyms. The use of by in passive structures is not a preposition but a particle. When you know the defining features of linguistic phenomena, you can observe them, study them, learn them and use them with confidence. Our English students who also study maths, science, biology, sport, history, geography, literature and the rest, understand very well that their success depends on a profound understanding of the terminology of their field(s). They also know that their professional success demands a professional level of English. Our students deserve as accurate a description of the language as we can provide them. Until you know that snowclones are an identified and labelled feature of the language, you can’t look them up, talk about them, research them, or tag the next one you hear as one. But now you can.

Ask not what students can do for you—ask what you can do for your students! If you have any other favourite, shareworthy snowclones, please add them in the comments below. It would be great to develop this.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|