The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

|

Has anyone ever used Google slides for their vocabulary notebooks? The only person I know who did so was me when I was studying Czech, but I’m sure I’m not alone. A Google slide can contain pretty much anything about a target word:

This slideshow has a few examples from my ever-expanding a slide show, which I would watch to revise my word notes. This often me prompted me to link a previously studied word to a new one. And as we all know, the relationships between words is crucial to understanding, choosing and using them. Relationships between people are also crucial, which makes the shareability (no, it’s not a nonce word) of Google slides a godsend to anyone studying with a study buddy or when a student wants to show their teacher their efforts. This is about studying vocabulary, not teaching it. As teachers, we can offer our students ways of studying vocabulary, but they have to do the work. One slide a day is quite a commitment when you fill it with all the features listed above. It is better to add new word data to existing slides. In fact, we are constantly and subconsciously adding to our dossiers on words when we are listening, watching and reading. One word a day may seem a tortoisly (yes, that’s a nonce word) slow march towards developing vocabulary breadth (size). And it would be if size were the only gain. However, to create a slide, the student engages in a lot of language and in the process, develops vocabulary depth. The tortoise always wins. You can see now that the picture shows a turtle (the aquatic relative of the landlubber tortoise) at some considerable depth.

I haven’t studied Czech for quite a while as it wasn’t much use in Uzbekistan where I was training for the BC and then for an American university for most of the last four years. But I’m back in Czechia now and I was chatting on Messenger with an ex last night and I met a new word: pokochat se. To fall in love. When I explored SkELL’s word sketch, the objects of pokochat se are such things as views, waterfalls, photos, nature. We were chatting about a concert. It’s time to re-open my Google slides.

0 Comments

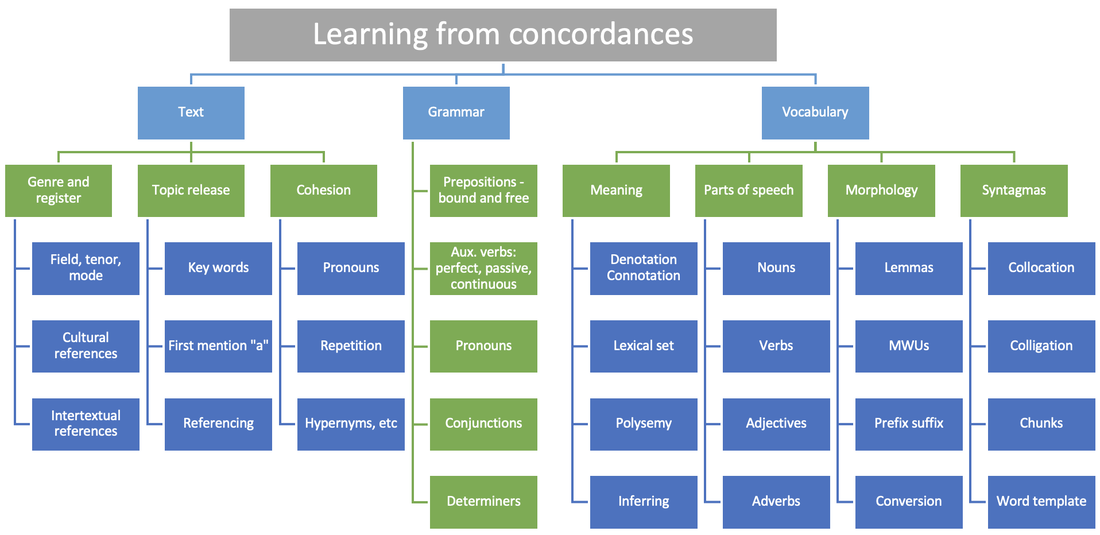

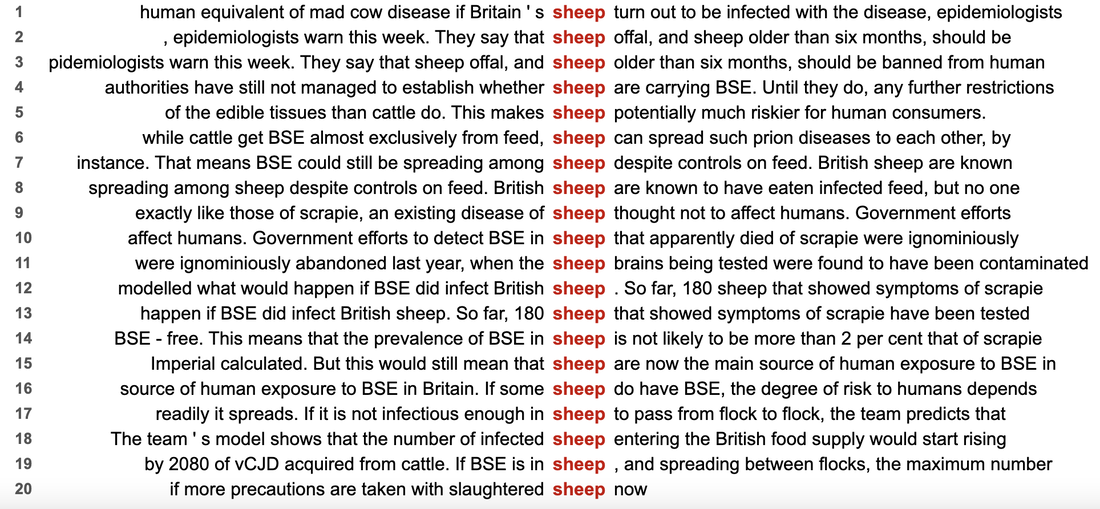

Yesterday, I read two current academic papers by esteemed colleagues. Is DDL dead? by Dr. Peter Crosthwaite and Prof. Alex Boulton. I co-edited a book of conference papers with Alex in 2012 and I presented my Discovering Academic English (2022) work in one of Pete's webinar series last year. The second paper, Generative AI and the end of DDL was written by the same Peter and Dr. Vit Baisa. I have been working with Vit for many years – he programs my VersaText and Pete's CorpusMate. The full titles of these works are in the references below. Data-driven learning (DDL) is an approach to studying language through treating language as data. Just as journalists, scientists and spies seek patterns in data so as to understand their subjects better and be able to make predictions, linguists including budding linguists, make and record their observations of features of language that they observe in authentic data. Being a discovery-based and inductive approach to language learning means that it is not suitable for every learning context, which is equally true of drilling, gap filling and using flashcards. DDL is one of many acronyms used in this article. They are listed at the end. Is DDL dead? reports very positive findings by researchers working in all corners of the globe over the last thirty years. Nevertheless, the authors identified a number of problems in the theoretical underpinnings of DDL, and with the actual corpus tools, and in the lack of cognitive studies, and even with the conduct of the research. They mention other drawbacks of DDL such as the technical knowledge required to use the tools, the fact that search tools work differently from other search engines, and that some corpus data is unsuitable for some learners. The second paper suggests that AI could potentially contribute to DDL but it is too soon to say. They argue that corpora still have a role to play in data-driven learning because corpus tools show where the data came from. Also, the data is authentic, unlike AI generated texts. The authors refer to them as hallucinations. They also point out that the inductive work done by students when working with corpora is actually done by ChatGPT, and not by the students. I have been immersed in DDL since the late 1990s, working with teachers and trainees and with students of academic writing. I have created e-learning courses, worksheets, books and have presented this work at conferences, some of which I have hosted and been on committees for. In the process, I have read many research papers and books on corpora and also on grammar, vocabulary and everything in between. So, I feel their pain. Many of the researchers cited in these two papers, and many more besides, regret that DDL has not become a standard modus operandi among internet savvy students and teachers in internet-wired homes and schools. The findings of these researchers has empirical credibility, but there are other issues that need to be addressed in order to alleviate the pain. And this is what I would like to focus on in this article and in several that will follow it. DDL focusses largely on the minutiae of language. The students are tasked with identifying patterns in the language by exploring the data. So far so good. But it is important that the students also learn how to record their findings, as they do in science experiments, for example. If they do not integrate their findings into previous schemata, much of the value of the task is lost. My Versatile Blank Book provides students with approaches to recording their findings systematically, intelligently, graphically and creatively. In addition, students need to apply their findings to their own language output. The students didn't discover the most frequent preposition that follows a particular adjective just to answer that guided discovery question. They discovered this to use the adjective confidently, to learn that different prepositions are used with different adjectives in patterned ways, and to learn how to observe such features of language. These affordances of DDL need to be articulated. The course books I have worked with over the years and seen at recent conference stands, and the resources which well-meaning teachers share in their Facebook and Pinterest groups, are not rich in opportunities for students to treat language as data or to exercise their intelligence and creativity. I remember my heart sinking when I once walked into Foyles bookshop on Charing Cross Road (London) to see "Celebrating 25 years of the world's best-selling grammar book", which many a reader of this post possibly also celebrated along with the author, Raymond Murphy. Such resources do not engage students in knowledge creation, rather they feed students a diet of matching activities and gap fills regardless of the age, level or motivation of the student. By the way, these are testing not teaching procedures. Grammar, vocabulary and everything in between are mostly poured into students' heads as information that can be presented and tested. This deprives students of the reality of language, namely the patterns and relationships that permeate everything we know about language. And we know a lot more about language than we did 50 years ago thanks largely to corpus studies. This diet of lower order thinking (LOTS) skills work deprives students of the opportunity to develop their knowledge about language (KAL) and the skill of learning language from language. It would be interesting to read the aims and objectives atop the lesson plans which DDL researchers have been studying. By the end of this lesson, the students will be able to … It would be equally interesting to read what the students write in their reflections on these lessons. From what I remember of the papers I read and edited quite some years ago, the research is mostly conducted under research conditions, not in classes led by teachers who are committed to this mode of language teaching and study. For the VersaText e-course I have just finished writing and which is currently being piloted by a few kind individuals, I created the taxonomy below. It will undergo some revision as it matures, but it nevertheless attempts to show what language students can learn from guided discovery tasks that require them to explore discrete aspects of language. It helps formulate aims and objectives, even though this linguistic minutiae is only a stepping stone to improved competence in the four skills. It also contributes to the development of their metacognitive competence. I suspect that any student or teacher of IELTS, TKT or DELTA could derive some benefit from this. Every feature of language begets a language learning task. For example, if we corpus aficionados want to study phrasal verbs and teach students how to study phrasal verbs, we need a clear definition of ‘phrasal verb’ and we need discovery tasks that can be solved through corpus consultation, and students need to be trained in reporting and applying their findings, just as any research scientist needs to do. One of the interesting things I have found in my EMI training is that university teachers of STEM and MBA subjects readily grasp how language can be treated as data and how patterns and relationships can be extrapolated. They just need to be told. In fact, one professor of horse surgery, upon his first introduction to corpus work, thanked me for making myself redundant (as a language teacher). He got it immediately. Many of our students major in STEM, MBA and medical subjects and do have the required mindset to learn language from language. Another issue besetting ELT is that KAL is not a high priority. No other subject so readily dismisses the theoretical foundation on which it is built (Marr and English, 2019). People place a lot of faith in osmosis, i.e., learners will acquire the language through vast exposure and by being required to do activities that will exercise what they know and force them to struggle to express ideas that they don't have the language for. Mind the gap! A considerable body of research supports my anecdotal experience that osmosis does not work for many people (Hinkel, 2006). For any learner who requires a professional level of a foreign language, attention to detail is essential. This may not be obvious to anyone who has never aspired to learn a foreign language to a high level. Language teaching seems to have leapfrogged language and is nowadays preoccupied with inclusion, empowerment, digital literacy, creativity, learner autonomy, gamification, global issues, critical thinking and soft skills (Kerr 2022). On a casual stroll through the list of topics that conferences cover, you will be unlikely to bump into many language topics. However, in order to pursue any of these worthy passions in a foreign language and with any degree of sophistication and nuance, the students need the principle resource for the job, namely a sophisticated and nuanced level of English. To facilitate this, double processing is recommended. This involves using the associated reading and listening for language as well as for content – explore the linguistic features of the key words and then use them in the writing and speaking tasks that follow. One of the reasons I created VersaText was to facilitate the study of the language of single texts. In this concordance of sheep from an article about BSE, we can see what the text is saying about the target word as well as how the author has said it. The aim is not to infer the meaning of sheep! I hope to finish in 2024 a B1 and a B2 activity books, both of which I would like to subtitle, More fun than Murphy, but better not. These books teach students language, about language and about language learning, using tools such as SkELL, VersaText and CorpusMate. The students will be doing “task-based linguistics” from the first to the last pages. AI was not integrated into these books when they were being drafted, but it would be profligate to ignore the opportunity that this new technology affords. If you would be interested in piloting these books with your students, please message me. I will say more about the pitfalls and potential of DDL in follow up posts. Thanks for reading and I look forward to your comments. AbbreviationsDDL: data-driven learning coined by Tim Johns (1990) AI: artificial intelligence LOTS: lower order thinking skills (cf. HOTS) IELTS: International English language testing system TKT: teachers knowledge test (a Cambridge exam) DELTA: diploma in English language teaching to adults EMI: English as a medium of instruction (university teachers teach their subject in English) STEM: science, technology, engineering, mathematics – a class of school subjects MBA: masters in business administration ELT: English language teaching KAL: knowledge about language BSE: Bovine spongiform encephalopathy a.k.a. mad cows disease a.k.a.: also known as ReferencesCrosthwaite, P. & Boulton, A. (2022). DDL is dead? Long live DDL! Expanding the boundaries of data-driven learning. In H. Tyne, M. Bilger, L. Buscail, M. Leray, N. Curry & C. Pérez-Sabater (Dir.), Discovering language: Learning and affordance. Peter Lang.

Crosthwaite, P. & Baisa, V. (2023) Generative AI and the end of corpus-assisted data-driven learning? Not so fast! Applied Corpus Linguistics. Vol. 3 Issue 3. Hinkel, E. (2006) Current Perspectives on Teaching the Four Skills. TESOL QUARTERLY Vol. 40, No. 1. Kerr, P. (2022) 30 Trends in ELT. CUP. Marr, T, and English, F. (2019) Rethinking TESOL in diverse global settings: The language and the Teacher in a Time of Change. Bloomsbury Academic. Thomas, J, & Boulton, A. (2012) Input, Process and Product: Developments in Teaching and Language Corpora. Masaryk University Press. Thomas, J. (forthcoming) Discovering Academic English. Thomas, J. (2022) Versatile Blank Book. Versatile Publisher. I’ve spent too much of the last forty years of my life learning foreign language vocabulary, as well as quite a lot of new words and concepts in my native English but this was through different means for different ends. Most of my early foreign language vocabulary study involved learning from bilingual lists or flashcards, labelling pictures, matching foreign words with pictures or English words, and filling in gaps in strings of unrelated sentences. Having no reason to believe that my teachers or course books had set out to hinder my progress or waste my time, I kept plodding along at first in Italian, then German and later Czech. And some Russian.

By the time I started studying Czech, I had also become an ELT teacher around the golden eras of the COBUILD project and the Lexical Approach. Corpora were also peeking their heads above the parapet (data driven learning). This was the early 1990s and it promised great things for a more sophisticated approach to vocabulary study, one in which we would study and teach the properties of words, their internal and external relationships with other words, their roles in creating meaning. It was a time when “learning to learn” and discovery learning were establishing themselves in ELT. Empowerment through linguistic competence was in the air. It took me some time to absorb and apply these new trends to my self-study of Czech, but I’m glad I did. It was more difficult to squeeze into my English teaching as we had to turn the pages of course books in lockstep with external syllabuses. A few weeks ago I was at IATELF Poland, where I picked up a sample course book, fresh off the press from one of the Big 4 publishers. Having been a teacher trainer for 25 years, it came as little surprise that the approach to studying and teaching vocabulary espoused in this brand new course book has no made no headway since the Headways I was teaching from 30 years ago. In my teacher training, I always offer teachers vocabulary teaching activities that engage higher order thinking skills, creativity, discovery learning, metacognitive strategies, the double processing of texts and negotiating meaning. Many of the activities derive from contemporary findings in linguistics, such as grammar patterns as properties of words, and the role of collocation in creating meaning. In the books I have published in the last ten years, I have also provided teachers with lesson plans, activities and resources that elevate the status of vocabulary to its rightful place, that prevent teachers from hindering students’ vocabulary development and that provide students with rewarding self-study procedures. Teachers want their students to be more fluent, accurate, sophisticated and idiomatic (FASI) and a solid grasp of vocabulary is an essential ingredient. |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|