The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

Sort of knowing a wordBack in 1991, I was teaching English on a weekend residential course in old Czechoslovakia. One of the assistants was a student in the arts faculty, where many years later I would find myself head of teacher training. In chatting with this student, she said, but you’re a native speaker – of course you know every word in the English language.

Max’s podcasts are mostly targeted at B1 level, and since his work is partly motivated by Krashen’s comprehensible input hypothesis, I listen for gist. My Russian is well below B1 but I comprehend a lot, and could probably retell the thrust of his monologues in English. This is thanks to my study of Russian, its closeness to Czech and its vocabulary having many English and international words, including those that have Greek and Latin origins. I should mention that there are many false friends between Russian and Czech, my favourite being užasný (amazing, awesome) vs. ужасный (terrible). Each of Max’s podcasts revolve around a single topic, so there is always the general context to help with the gist, but since he only speaks Russian in the podcasts, you have to infer the topic as well. There is no time during the podcast to analyse his use of words so that you might be able to use them in the cotexts that he employs. It is challenging to observe collocation, colligation and chunks on a single listening, and it is not why we listen. So, while the gym has a leg abduction machine, I would say that our brains have a language abduction machine. Abductive reasoning is a form of logical inference that seeks the simplest and most likely conclusion from a set of observations. We do a lot of abducting when our comprehensible input is only just comprehensible.

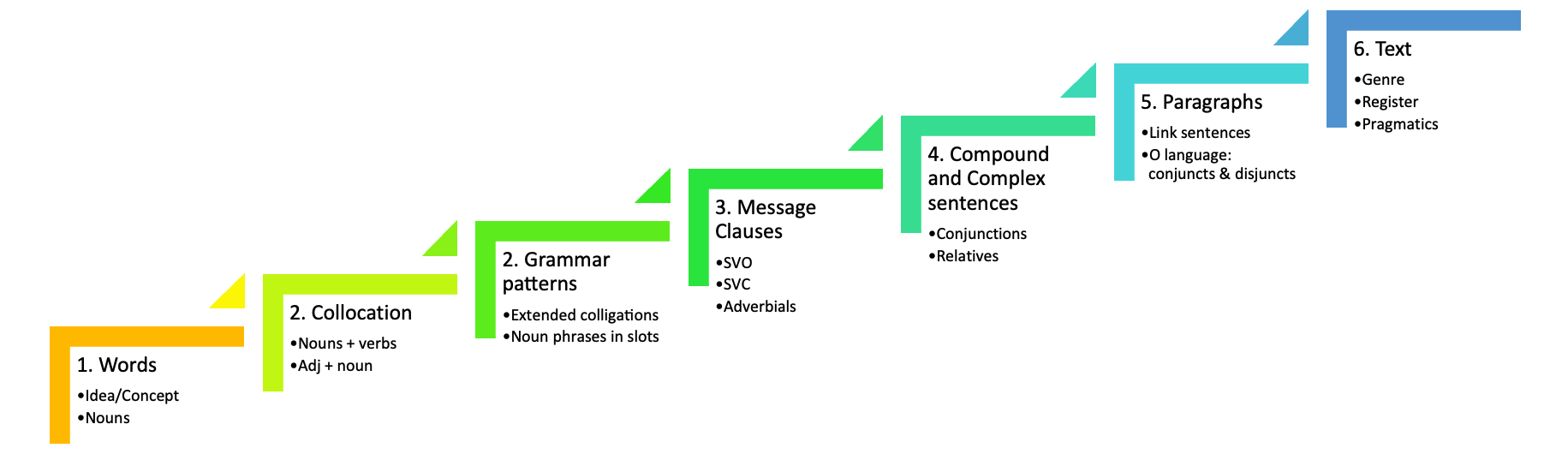

Our word knowledge typically emerges over time in both first and second language acquisition contexts. In FLA our word knowledge mainly accrues through multiple exposure, although we do use dictionaries, chat to friends about new and surprising uses of words. We even read and watch videos about language. In SLA, our word knowledge mainly accrues through structured study, which is both motivated and reinforced by exposure as we read, write, speak and listen. The emergent stages of vocabulary competence can be described thus:

An important application of this continuum is in the revision and recycling of previously studied words. We obviously cannot learn everything there is to know about a word on its first encounter, so this helps temper our expectations. We can also structure the word knowledge that we add in successive revisions. This layering is especially valuable in creating our own vocabulary workbooks and flashcards. I am devoting some pages to flashcards, the use of AI, and this continuum in the book I am writing at the moment. It might have the bumptious title, How to Learn Vocabulary Properly. We’ll see!

0 Comments

One swallow does not summer make

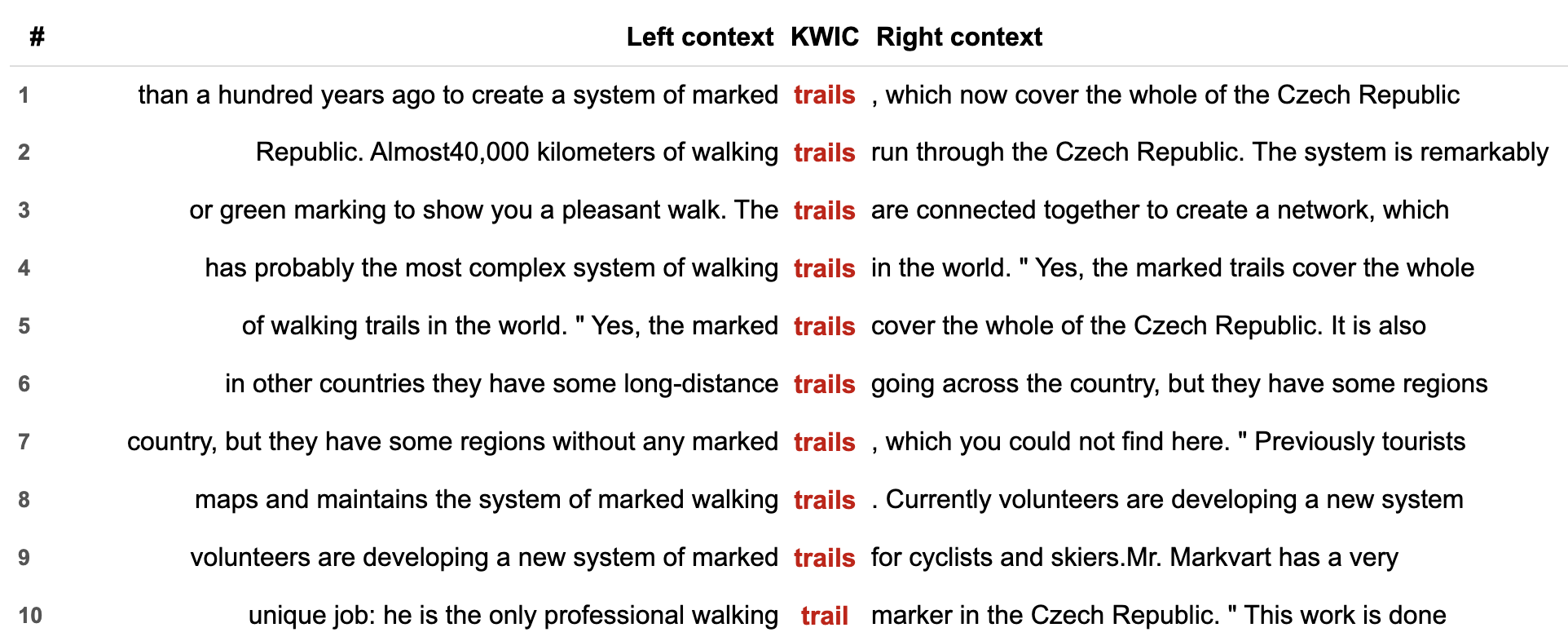

Hoey in fact studied foreign languages so that he could experience the processes of language learning and the practical applications of linguistic and pedagogical theory. When he was observing language in context, that is by reading and listening, he would notice certain collocations but he needed proof of their typicality before he could consider them worth learning. Just because someone has combined a pair of words does not mean that this combination is a typical formulation in the language. The lexicographer, Patrick Hanks (1940–2024) felt the same: Authenticity alone is not enough. Evidence of conventionality is also needed (2013:5). Some years before these two Englishman made these pronouncements, Aristotle (384–322 BC) observed that one swallow does not a summer make. Other languages have their own version of this proverb, sometimes using quite different metaphors, but all making the same point. In order to ascertain that an observed collocation is natural, typical, characteristic or conventional, it is necessary to hunt it down, and there is no better hunting ground for linguistic features than databases containing large samples of the language, a.k.a corpora. In the second paragraph, Hoey experienced the processes … Is experience a process a typical collocation? This is the data that CorpusMate yields: In the same paragraph, we have the following collocation candidates:

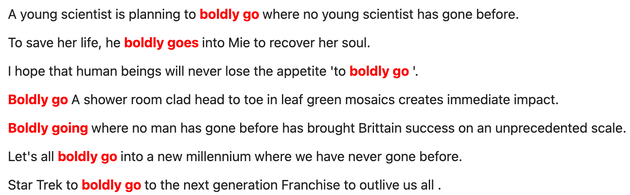

Here is some more data from CorpusMate. In the following example, we have a wildcard which allows for one element to appear between the two words of the collocation. Even in these first 12 of the 59 results, other patterns are evident.  The process of validating your findings through multiple sources or methods is known as triangulation, and it is an essential stage in most research. When we train students to triangulate their linguistic observations, it is quite likely that they are familiar with this process from their other school subjects. This is not just a quantitative observation, i.e. this collocation occurs X times in the corpus. It is qualitative as well: the students observe other elements of the cotext, such as the use of other words and grammar structures that the collocation occurs in. They might also observe contextual features that relate to the genres and registers in which the target structure occurs. They are being trained in task-based linguistics as citizen scientists, engaging their higher order thinking skills as pattern hunters. This metacognitive training is a skill for life that will extend far beyond the life of any language course they are undertaking. Triangulation does not apply only to collocation. Any aspect of language can be explored in this way. You may have noticed the word order in the idiom: does not a summer make. Many people have run with this curious word order and exploited it creatively. It is thus a snowclone. Here are some examples from SkELL. Respect our students' intelligence and equip them to learn language from language. ReferencesCroswaithe, P. & Baisa, V. (2024) A user-friendly corpus tool for disciplinary data-driven learning: Introducing CorpusMate International Journal of Corpus Linguistics.

Hanks, P. (2013) Lexical Analysis: Norms and Exploitations. MIT. Hoey, M. (2000) A world beyond collocation: new perspectives on vocabulary teaching. Teaching Collocation. Further Developments in the Lexical Approach. LTP (ed. Lewis, M.) The undersung "and" A sign seen recently in Tashkent. I was adding a little section on fuzzy and fuzziness to my #AfterIELTS course book last week – it is currently on p.72 but that may change between now and its imminent publication. The word fuzzy sounds about as academic as chunk, yet both are revered linguistic concepts. Anyway, whilst writing about fuzzy, I was reminded of the “and” relationship that conspicuously appears in most #wordsketches of most words. Without an awareness of this mighty relationship, however, it is easily overlooked. Conspicuous is it not.

Our fuzzy examples, however, are properties of the word. Make a word sketch for pretty much any noun, verb, adjective, or adverb in the English language and you will find words that and links it with. The more arcane the word, the more arcane the partners. See arcane, for example. Search for words that are in a text you are studying or on a word list you are working with. Explore the "and" relationship by clicking on a word to see it in sentence examples. For example, in the "and" relationship of class, we see among others:

Clicking on category shows 40 sentences related to categorisation. Once again, this represents the way this topic is written and spoken about. Remember that we do not need to read and grasp the sentence examples that corpus searches yield. A concordance page is not a text – it is a source of language data that we skim and scan to identify patterns of normal usage from which we learn how the language works so that our use of the foreign language approximates that of the many native speakers whose output has turned up in the corpus. The "and" pattern, connecting two words of the same part of speech and with similar semantics, often offers lexical support. Rather than expressing something new, this quasi repetition reinforces the meaning or general impression being communicated. This is particularly noticeable with subjective and emotive words. Look at the "and" relationships of: There is also the matter of word order. Words in these and relationships are usually said in a set order.

As language teachers and speakers of foreign languages, we are always interested in the properties of words. Knowing a word’s patterns of normal usage is key to using words as native speakers do. And the confidence that emerges from this knowledge impacts on fluency. Reach for the stars and draw a constellation.How often have you seen claims like these?

Who would make such claims? Certainly not someone who has achieved a high level of competence in a foreign language. As an eternal language student, and a language teacher and a teacher of teachers, I am pretty certain that you and I have worked hard to get to where we are in our foreign languages. It was not effortless, it wasn’t a breeze and no progress was made while we were asleep. I was so desperate to improve my vocabulary, that I used to sleep with my dictionary under my pillow. No I didn’t, but that is the impression you get from some of these slogans. Learning a language is hard work and there ain’t nothin’ wrong with hard work. Never confuse hard work with hard labour. Hard doesn’t mean boring and monotonous and it doesn’t mean frustrating and unrewarding. The hard work we do when learning a language involves planning, monitoring and revising. It involves understanding what we are learning, which in turn involves connecting what we already know with what is new to us. Hard work involves practising what we have learnt so that it becomes automatic. Hard work involves using our time efficiently, choosing approaches that work for us. This requires us to assess or critique the approaches to language study that are introduced to us if we are fortunate enough to have various approaches. It is worth reflecting on how many different learning experiences we are having while studying – the learning #affordances of an activity. For example, if we are learning a set of English words with their first language equivalents, whether in written lists, on paper or electronic flashcards, in a computer game or being tested by our study buddy, the only connection we make is between the L1 and L2 word. We do not learn how the word is used. This leads us to assume that the L2 word is used in the same way as it used in L1 and this is okay when it works. It is not okay the rest of the time. Psycholinguists refer to this assumption as the semantic equivalence hypothesis (Ijaz 1986, Ringbom 2007). Another issue with learning L1–L2 pairs is the mental processing of the L2 word: what is your mind doing whilst trying to remember a word? Lower order thinking does not make for a rich learning experience. When we are critiquing our approaches to vocabulary study, we need to consider how many different features of words we are learning at the same time. However, when we study the vocabulary of a text in a text, we see how keywords are used differently each time they are used. Yes, their different uses create different messages which means that the author is telling us something new about the keyword each time it is used. These different messages involve different words, which means we can make a diagram of a keyword as it is used in a text. I call these diagrams Word Constellations. We can identify a key word and highlight all of its occurrences in the text, then highlight the words that are used with it. I prefer to do this with #VersaText because it is easy to see the left and right cotexts of keywords in a concordance. You can do this with at least several key words in the text. In critiquing this approach, we need to consider how much the students learnt during the time spent.

If they didn't create a word constellation of a key word in a text, what did they do? How did they spend their time? What learning took place? Once we have a keyword in its multiple cotexts, we can use them as the bases of our own sentences. We might like to use them to form questions to discuss with our study buddy or our favourite AI tool. Here are some simple examples of a chat with Perplexity.ai. Hi. I'm a B1 student of English. Will you be my study buddy today? Of course! I'd be happy to help you with your English studies.

Is this time-consuming? Is it a good use of our time? Are we having strong learning experiences? Are connections forming in our minds that have a high chance of becoming permanent? I used bilingual lists for many years, long after I needed to. I think that if I were to start another foreign language, I would need them as a beginner. But applying what I have actually known for a long time, I would move as quickly as possible to studying words with their natural cotexts. It may be the case that people who make claims like those at the top of this article do actually teach vocabulary in cotext, but from the courses and resources that I have seen over the years, this does not seem very likely. If you or your students ever create word constellations, I’d love to see them. And I would love to know what the process led to. Feel free to join the VersaText Facebook Group where you can share your experiences and learn from others. ReferencesIjaz, I. H. (1986). Linguistic and cognitive determinants of lexical acquisition in a second language. Language Learning, 36(4): 401-451

Ringbom, H. (2007). Cross-linguistic similarity in foreign language learning (Vol. 21). Multilingual Matters. Veselá, Z. (2003) Czech Republic’s unrivalled system of marked walking trails. Radio Prague International, 5.12.2003. Collocation and VersaTextI had an email from a teacher who loves using my VersaText tool with his students. In addition to the very welcome and rarely received praise for VersaText, he was enquiring into the possibility of adding a collocation feature. As you know, VersaText works with single texts, its slogan being, “learning language from language, one text at a time”, collocations are vanishingly rare. In fact, “vanishingly rare” is a strong collocation in English. Check out the examples in #SkELL.

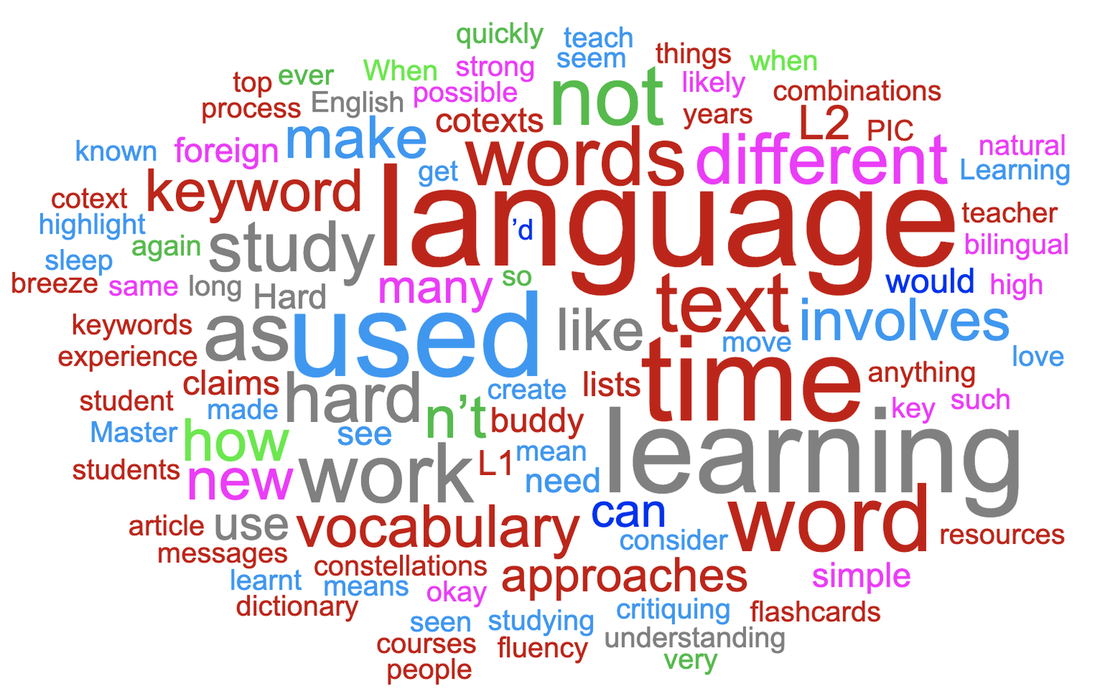

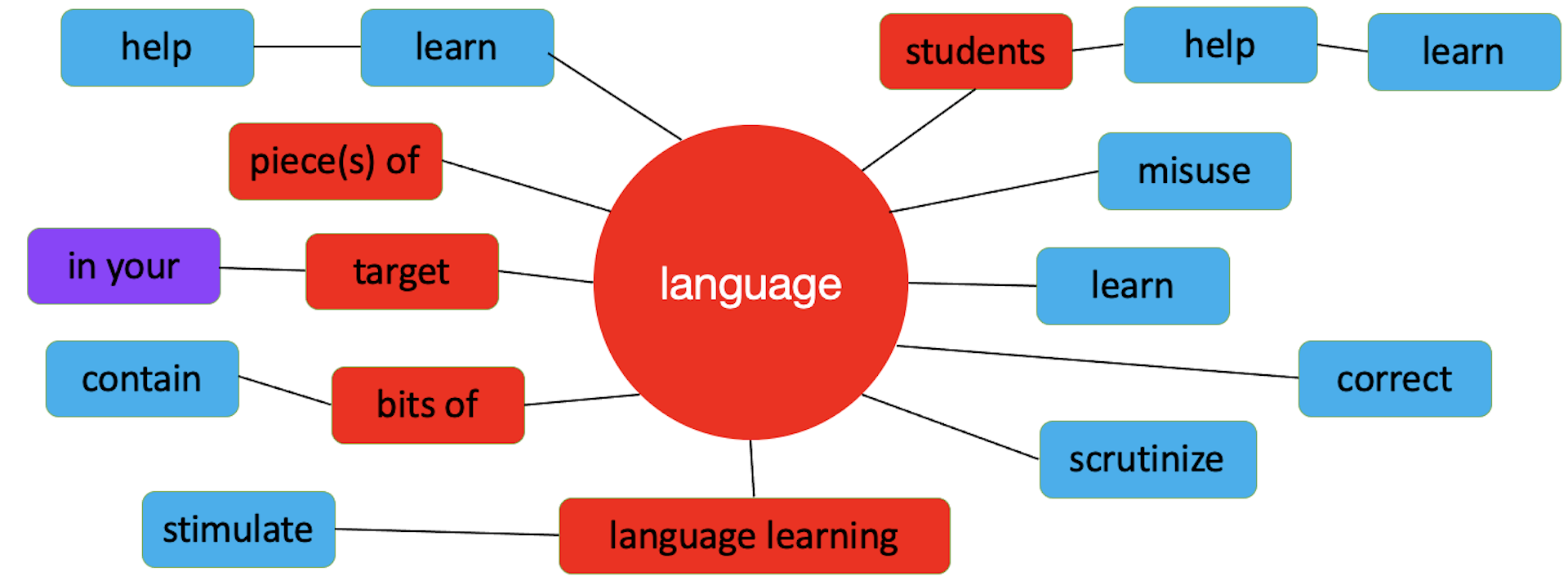

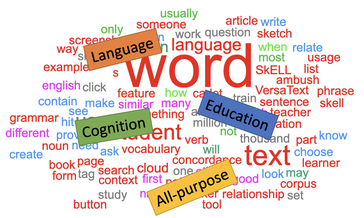

#Collocation is defined variously. First and foremost, collocation consists of two content words of different parts of speech. Compound nouns and adjectives, phrasal and delexical verbs are not collocations. And neither are words that combine with that/ -ing / inf / wh-/prepostions. These are colligations and offer very little choice, if any. You’ve all seen gap fills in coursebooks and exams that test this. Collocation does permit some variation, but within limits of acceptability if you are going to use the patterns of normal usage of the language. One category of definitions of collocation revolves around statistical frequency. These definitions rely on the number of times words occur in close proximity to each other. The verb collocates of trouble, for example, occur frequently within four words before and/or after the noun in SkELL's huge sample of English. Other definitions of collocation are phraseological: cause trouble is the core of a clause, which is the essential structure that creates Messages, which in turn constitutes text. Up the Hierarchy of Language we go! Most key words in most texts collocate with different items because the author is telling us something new about the word. And this is why a collocation tool in VersaText would be by and large redundant. One thing we can be sure of in a text is that the author is not going to repeat the same message repeatedly, again and again, over and over, unless they have some rhetorical reason for doing so. Here is an example. In VersaText’s sample text, Learning Zone (a transcript of a TED Talk), we see that the verb spend is frequently used with time, and with other time words, e.g. minutes, hours, our lives. It occurs 13 times in the text. Time occurs 28 times in the text and is used thus: CTRL F in the browser highlights the nominated word as it occurs in the cotext of the target word. Improve occurs 15 times in the text, each time in a different Message. This is far more typical of words in text than a frequently used collocation like spend time. Go to VersaText, select the Learning Zone text from the list, then click Wordcloud at the top. If you want the lemma of improve, for example, choose the lemma radio button under the word cloud. Click on any word to see its concordance in this text. This motivates many discovery learning tasks for the students. If you want to learn more about studying and teaching English with VersaText, click the Course button at the top of the VersaText pages. My phraseological approach to collocations in single texts is the Word Constellation. See my blog post linked below. This is a word constellation. It is built upon a VersaText concordance of the word language in text about language learning.

Snowclones adriftIt is a truth universally acknowledged, that a university student in possession of a strong academic vocabulary will be well on the way to toughing out their studies, for we know that when the going gets tough, the tough rush headlong into their studies and boldly go where no student has gone before. And other such exploitations of well-known expressions. You can see more examples of them in the SkELL corpus. And when you do explore them in SkELL, you can read the full sentences and make a wide range of observations. You can discover their original forms and observe how various people have exploited them. And talked about them. Remember that corpora generally consist of thousands of texts created by different individuals and a search provides a sample of the target word or structure. Because SkELL’s corpus is drawn from the internet, you can copy a sentence and Google it to see it in its source text and consider the author’s motivation for using it. You can consider the genre and register of the text: it is unlikely that they would be used in academic papers or in formal conversations. As you have probably heard, Eskimos have 17 words for snow, far more than any other language. This claim is as fatuous as the Great Wall of China being the only man-made object visible from space. And both of these statements are also snowclones, the term used for these linguistic exploitations. I have it on good authority (Wikipedia) that the term was coined by Glen Whitman, economics professor, in 2004, and the linguist, Geoffrey Pullum, endorsed it. Whitman’s inspiration for the term was the fatuous Eskimoan snow claim. Here are a few more snowclones that I have collected over the years. They have various origins and standard uses in English, but all are variously exploited as snowclones.

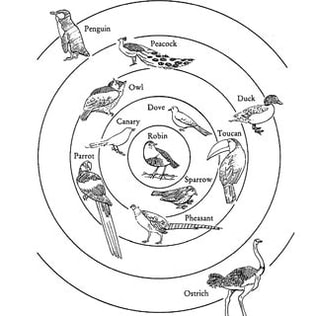

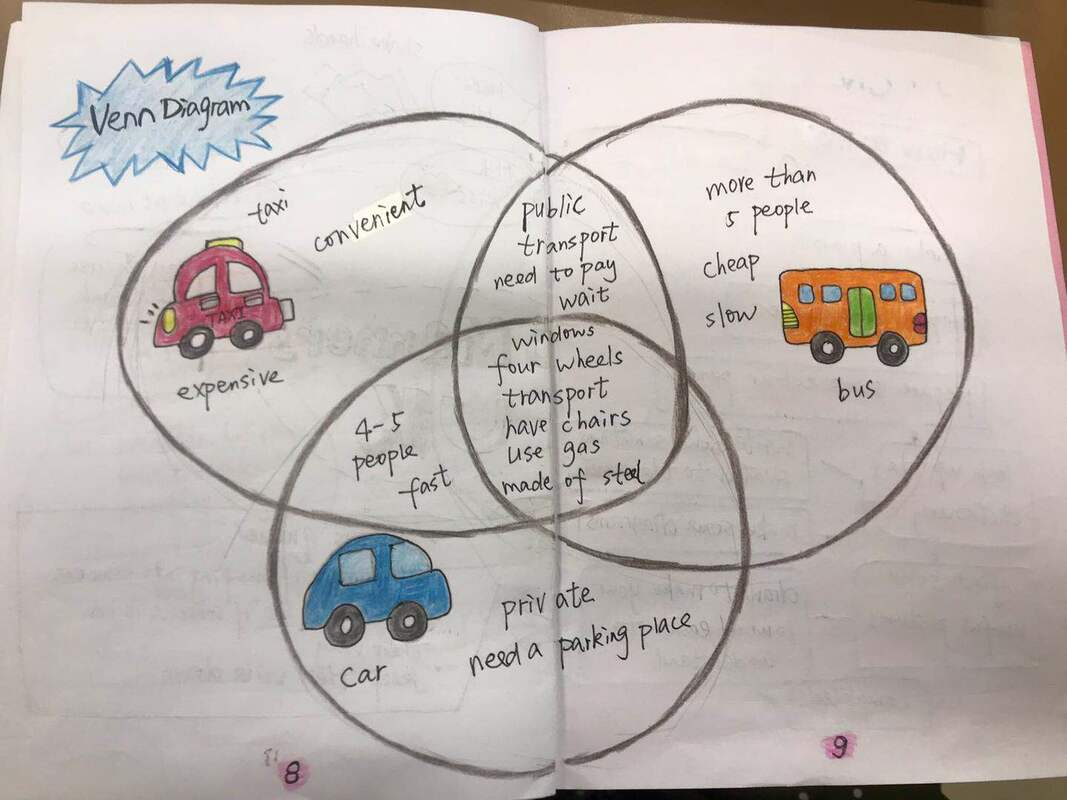

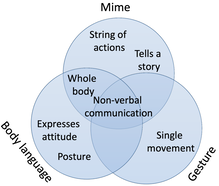

Like all linguistic phenomena, snowclones have been in existence much longer than the term coined to describe them. A term endows a phenomenon not only with a certain gravitas but a recognition that it has a set of features that an entity needs to be worthy of the name. If it has all of the required features it is a prototype (Rosch). Eleanor Rosch Most things deviate to some extent from prototypes, but if they have enough of the features in an adequate proportion, they can be thus labelled. The beloved example of semanticists is birds: which features of pigeons, eagles, emus, penguins and pterodactyls do they possess to be categorised as birds? Another fine example is the English language: which features of English do spoken Texan, Irish football journalese, and academic written English all possess? This makes for an interesting Venn diagram and it leads to a description of “core” English. A nice activity, by the way! Terms are of much use to language students and misuse impedes their progress. We are all familiar with the misnomers, past tense and past participle. As Michael Lewis convincingly conveyed, the past tense is actually about remoteness – in time, in reality, and in social distance. The past participle is a non-finite form and by definition cannot express time. Compound nouns and phrasal verbs are not collocations, and delexical verb structures are neither collocations nor phrasal verbs. Restaurant, bistro and canteen are co-hyponyms, not synonyms. The use of by in passive structures is not a preposition but a particle. When you know the defining features of linguistic phenomena, you can observe them, study them, learn them and use them with confidence. Our English students who also study maths, science, biology, sport, history, geography, literature and the rest, understand very well that their success depends on a profound understanding of the terminology of their field(s). They also know that their professional success demands a professional level of English. Our students deserve as accurate a description of the language as we can provide them. Until you know that snowclones are an identified and labelled feature of the language, you can’t look them up, talk about them, research them, or tag the next one you hear as one. But now you can.

Ask not what students can do for you—ask what you can do for your students! If you have any other favourite, shareworthy snowclones, please add them in the comments below. It would be great to develop this. Imperfect passiveI asked ChatGPT for ten passive sentences about the topic of connectionism. As usual, the sentences are bland and inauthentic. But this is one was also problematic.

Consider yourself warned.A day in the life

My Tashkent students threw an end of "Vocabulary Strategies" course party. Everyone knows what a word is, right?So, how many words are in this sentence?

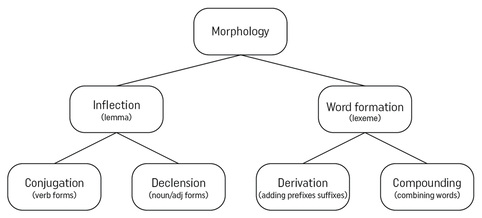

If our definition of a word is a string of letters surrounded by a space or punctuation, it is the same as our computer’s word counts. These are known as orthographic words. We count strike and struck as two word forms of the lemma strike. The other word forms are strikes, striking, stricken. We can distinguish tokens - the number of orthographic words in a sentence or text from types - the number of different word forms. In the next sentence, strike is a noun and a verb. This is variously known as conversion and zero derivation. These are different lemmas – a lemma is the set of word forms of one part of speech. The noun lemma is strike, strikes.

Is flight attendant one word or two? In the next sentence, we have a phrasal verb and a compound adjective.

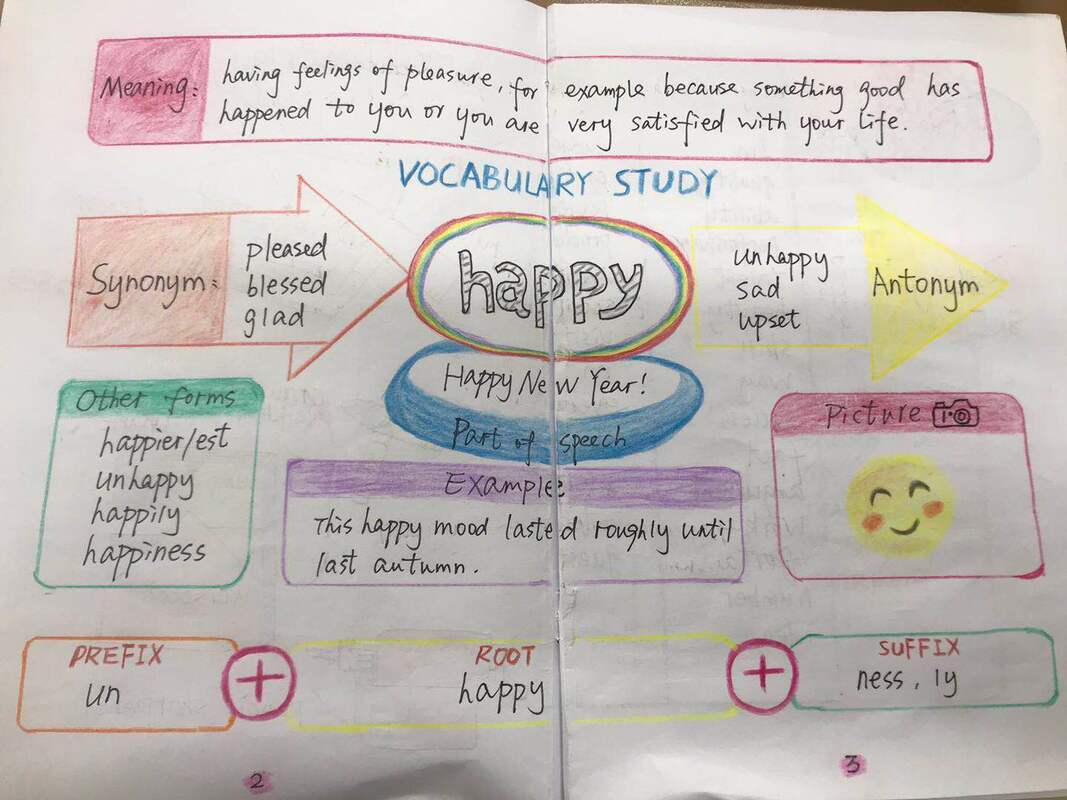

The two orthographic words create these lexemes, i.e. units of meaning. Lexemes can be single words or compounds. Flight attendant is a compound noun, i.e. a lexeme. It is not a collocation because the two words in a collocation retain their individual meanings, e.g. end strike in the second sentence and good approach in the third – best being part of the lemma good. The set of word forms that are formed from a single word are a word family. If you fill the Taxonomy of Morphology with all the word forms of strike, you will have depicted its word family. In addition to the word forms of strike we have already seen, it might include misstrike, overstrike, outstrike, pre-strike, re-strike, strikeout, strike-through, striker, striking (adj), strikingly. Taxonomy of Morphology This may seem like a lot of trouble to go to to answer a question about the number of words in a sentence. In fact, counting words is just a task that draws attention to the issue. Having a superior conceptual grasp of “word” allows students to complete the Taxonomy of Morphology for any lexical items they are studying. Ideally they would observe them whilst reading, listening and watching and add them to their stunningly visual or visually stunning vocabulary notebooks. This would be the impetus for seeking out more word forms of a target word. Halliday considered the term lexical item less indeterminate than the folk-definition of word as he called it. Our students deserve more than the folk definition. They don’t have folk definitions of concepts of physics, chemistry, biology, literary devices and other conceptual networks that they study at secondary school and beyond. They don’t even have folk definitions of the passive voice, articles, conditionals, subordinate clauses and other grammatical concepts when learning English. Their knowledge of vocabulary is however profoundly superficial. We are not helping our students develop their active vocabulary if they cannot distinguish a collocation from a compound noun, if they do not know the properties of phrasal verbs and delexical verb structures, if they do not know that the relationship between vehicle, car and sedan is systematic, if they are unaware of the patterned use of prepositions with nouns, verbs and adjectives as comprehensively demonstrated in these two books from COBUILD. If students are to observe the properties of the words that they encounter in their input so that they can use them in their output, they need to know what a word is and what the properties of different types of words are. Students can learn a great deal of language through learning about language, and this in turn equips them to learn. The standard fare of bilingual lists, flash cards and gapfills reside on the bottom rung of Blooms’ Taxonomy, unlike creatively recording their observations of language in use. Every property of a word begets a learning task. When students structure their vocabulary in mind maps, word roses, word constellations, flow charts, Venn diagrams, semantic features tables, word profiles and the rest, they are engaging higher order thinking skills, they are negotiating with classmates, they are using a lot of words that are related to the target words, some of which may be new or being used in new ways, while others are being recycled. Their higher order thinking skills are also being exercised when they annotate vocabulary features of whole texts. They can trace the topic trails, the different uses of repeated keywords, the collocations and colligations that the author has used. When the students are engaged in wide reading and observe patterns in the use of key words in CLIL, ESP, EMI or general English projects, they learn their genre and register specific usages. This plays a significant role in acculturating students into the conceptual and linguistic milieu of their field.

Only students can learn vocabulary. Teachers can teach them about vocabulary and provide them many vocabulary learning strategies, many of which depend on an awareness of lemmas and lexemes, types and tokens, collocation and colligation, word templates and topic trails. And the rest! There is much to be done. Once you have learned how to ask questions, you have learned how to learnThe title of this post comes from Postman and Weingartner's influential book, Teaching as a Subversive Activity (1969). This thinking can be applied to the study and teaching of any subject. In terms of language learning, it is safe to say tht once students are equipped with new linguistic concepts, they can formulate hypotheses and develop a new range of questions that can then be explored in texts. They write: Knowledge is produced in response to questions. And new knowledge results from the asking of new questions; quite often new questions about old questions. Here is the point: once you have learned how to ask questions – relevant and appropriate and substantial questions – you have learned how to learn and no one can keep you from learning whatever you want or need to [1] know. Their statement, once you have learned how to ask questions, you have learned how to learn, could be a poster in every staffroom in the world. Learning how to learn lies at the heart of the metacognitive dimension of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Producing one’s own knowledge accords with Vygotsky’s knowledge creation and it happens through the data-information-knowledge. Postman and Weingartner’s fifty year-old revolutionary little book remains remarkably relevant. In their chapter, What's worth knowing, the authors bombard us with pages of questions that teachers could well discuss with their students. The first set of questions extracted below, prompts students to consider the nature of change, which they really should ponder if they are going to be subverted! What is 'progress'? What is 'change'? What are the most obvious causes of change? What are the least apparent? What conditions are necessary in order for change to occur? What kinds of changes are going on right now? Which are important? How are they similar to or different from other changes that have occurred? The second extract deals with relationships, another leitmotif of Learning Language from Language (the name of my unfinished book from which this blog post is extracted). What are the relationships between new ideas and change? Where do new ideas come from? How come? So what? If you wanted to stop one of the changes going on now (pick one), how would you go about it? What consequences would you have to consider? The third extract relates to the fundamental importance of language. What does man's language permit him to develop as survival strategies that animals cannot develop? How might man's survival activities be different from what they are if he did not have language? What other 'languages' does man have besides those consisting of words? What functions do these 'languages' serve? Why and how do they originate? Can you invent a new one? How might you start? The final extract contains questions about questions and questioning. They are for teachers to ask themselves. Will your questions increase the learner's will as well as his capacity to learn? Will they help to give him a sense of joy in learning? Will they help to provide the learners with confidence in his ability to learn? In order to get answers, will the learner be required to make inquiries? (Ask further questions, clarify terms, make observations, classify data, etc.?) Does each question allow for alternative answers (which implies alternative modes of inquiry)? Will the process of answering the questions tend to stress the uniqueness of the learner? Would the questions produce different answers if asked at different stages of the learner's development? Will the answers help the learner to sense and understand the universals in the human condition and so enhance his ability to draw closer to other people? Processing such questions leads to ditching old modes of thinking and replacing them with new modes of thinking, the very definition of subversion.

|

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|