The Versatile ELT BlogA space for short articles about topics of interest to language teachers.

Subscribe to get notified of

|

|

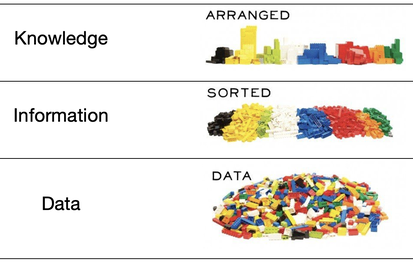

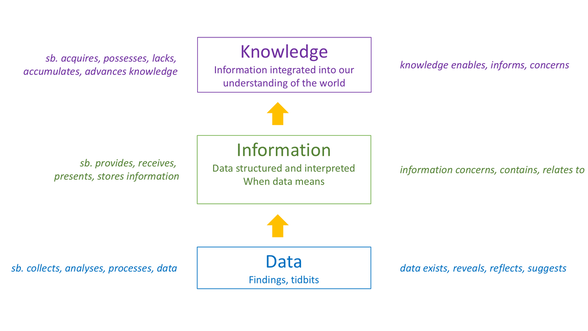

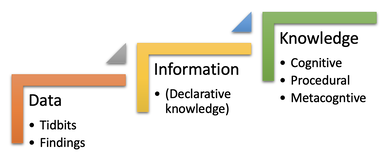

The hunt for DIK pics on the web is an eternal source of fascination. The yield reveals some quite interesting conceptualisations that I like to share with my students. Most of my students in the last 25 years have been either pre-service teachers doing MA TESOL courses at university, or in-service language and EMI teachers doing short intensive courses, mostly for the British Council. Lego affords arguably the most graphic representation of the data-information-knowledge paradigm. Data as a random collection of tidbits; information as patterns and relationships in the data; knowledge as something meaningful. Some of my training courses start with an activity, Three texts, Three groups, Three presentations (#58 in The Book of How to do things in ELT). The class is divided into three groups and each group receives a variety of texts about different aspects of their topic. The students read their texts, discuss the content with their group, prepare a poster that represents their understanding, then present it to the rest of the class. This is an activity with multiple affordances. The three posters are displayed on the classroom walls and referred to frequently through the rest of the training. We refer to the DIK poster when exploring inductive approaches such as discovery learning. We contrast students being given information to memorise and regurgitate with students being tasked with finding patterns and relationships in the data they collect. This leads to issues of trust and respect – we respect our students' intelligence enough to trust them to work out what to learn and how to learn. We trust that they will learn more deeply if they have to work it out for themselves, and we trust that they will benefit from learning how to learn, i.e., metacognitive training. The data-information-knowledge paradigm also demonstrates the role that collocation plays in distinguishing words which might be thought of as near synonyms. It is clear from this lexical data, drawn from a corpus of authentic samples of English, that data, information and knowledge perform different actions when they are the subjects of verbs; they are the objects of different verbs also. We ask our students to draw conclusions about these three words from their collocations. Students come to use the words with more confidence having observed their use by multiple native speakers. The students can even extend the role of collocation to other vocabulary that they are learning, if they don't already. By now, they have seen collocation at work: we show them how to obtain data, convert it into information and apply it to their own use of language. Applying it to their own use of language is an application of procedural knowledge. Any information which integrates with the information and knowledge that we already hold becomes new knowledge, ergo knowledge creation. When students conduct a survey, in a Find Someone Who activity, for example, they are collecting data. When they get together and process their data, they are arriving at information from which they can draw conclusions. They have created cognitive knowledge which may influence their view on the topic and on their classmates.

A reading or listening text serves as a source of language data. The teacher's guided discovery tasks position students to learn language from language, once again creating knowledge and developing their confidence in using the words, phrases, structures and any other target feature of the language that are observed in the current text.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

To make a comment, click the title of the post.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|